At 6.30am on Thursday October 29 2009, Friederike Meckel Fischer’s doorbell rang. There were 10 policemen outside. They searched the house, put handcuffs on Friederike, a diminutive woman in her 60s, and her husband, and took them to a remand prison. The couple had their photographs and fingerprints taken and were put in separate cells in isolation. After a few hours, Friederike, a psychotherapist, was taken for questioning.

She knew she was “really in trouble” when the officer read back to her the promise of secrecy she had each client make at the start of her group therapy sessions: “I promise not to divulge the location or names of the people present or the medication. I promise not to harm myself or others in any way during or after this experience. I promise that I will come out of this experience healthier and wiser. I take personal responsibility for what I do here.”

The Swiss police had been tipped off by a former client whose husband had left her after they had attended therapy. She held Friederike responsible for his departure.

What got Friederike into trouble were her unorthodox therapy methods. Alongside separate sessions of conventional talk therapy, she offered a catalyst, a tool to help her clients reconnect with their feelings, with people around them, and with difficult experiences in their lives. That catalyst was LSD. In many of her sessions, they would also use another substance: MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine), also know as ecstasy.

Friederike was accused of putting her clients in danger, dealing in drugs for profit, and endangering society with “intrinsically dangerous drugs”. Such psychedelic therapy is on the fringes of both psychiatry and society. Yet LSD and MDMA began life as medicines for therapy, and new trials are testing whether they could be again.

Psychedelic effects

In 1943, Albert Hofmann, a chemist at the Sandoz pharmaceutical laboratory in Basel, Switzerland, was trying to develop drugs to constrict blood vessels when he accidentally ingested a small quantity of lysergic acid diethylamide, LSD. The effects shook him. As he writes in his book LSD: My Problem Child:

“Objects as well as the shape of my associates in the laboratory appeared to undergo optical changes … Light was so intense as to be unpleasant. I drew the curtains and immediately fell into a peculiar state of ‘drunkenness’, characterised by an exaggerated imagination. With my eyes closed, fantastic pictures of extraordinary plasticity and intensive colour seemed to surge towards me. After two hours, this state gradually subsided and I was able to eat dinner with a good appetite.”

Intrigued, he decided to take the drug a second time in the presence of colleagues, an experiment to determine whether it was indeed the cause. The faces of his colleagues soon appeared “like grotesque coloured masks”.

He writes: “I lost all control of time: space and time became more and more disorganised and I was overcome with fears that I was going crazy. The worst part of it was that I was clearly aware of my condition though I was incapable of stopping it. Occasionally I felt as being outside my body. I thought I had died. My ‘ego’ was suspended somewhere in space and I saw my body lying dead on the sofa. I observed and registered clearly that my ‘alter ego’ was moving around the room, moaning.”

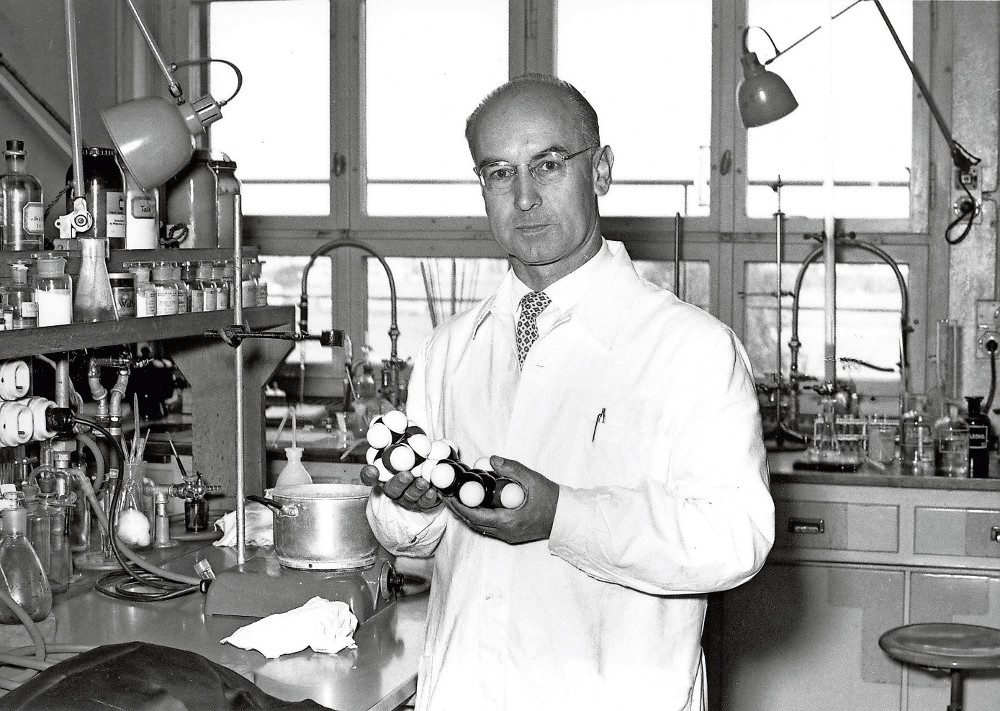

Albert Hofmann’s accidental discovery of LSD’s effects led to it being used in psychiatry.

Albert Hofmann’s accidental discovery of LSD’s effects led to it being used in psychiatry.

Lasting effects

But he seemed particularly struck by what he felt the next morning: “Breakfast tasted delicious and was an extraordinary pleasure. When I later walked out into the garden, in which the sun shone now after a spring rain, everything glistened and sparkled in a fresh light. The world was as if newly created. All my senses vibrated in a condition of highest sensitivity that persisted for the entire day.”

Hofmann believed it was of great significance that he could remember the experience in detail, and that the drug could hold tremendous value to psychiatry. The Sandoz labs, after ensuring it was nontoxic to rats, mice and humans, soon started offering it for scientific and medical use.

One of the first to start using the drug was Ronald Sandison. The British psychiatrist visited Sandoz in 1952 and, impressed by Hofmann’s research, left with 100 phials of what was by then called Delysid. Sandison immediately began giving it to patients at Powick Hospital in Worcestershire who were failing to make progress in traditional psychotherapy.

After three years, the hospital authorities were so pleased with the results that they built an LSD clinic. Patients would arrive in the morning, take their LSD and then lie down in private rooms. Each had a record player and a blackboard for drawing on. Nurses or registrars would check on them regularly. At 4pm the patients would convene and discuss their experiences. A driver would then take them home, sometimes while they were still under the influence of the drug. Around the same time, another British psychiatrist, Humphry Osmond, working in Canada, experimented with using LSD to help alcoholics stop drinking. He reported that the drug, in combination with supportive psychiatry, achieved abstinence rates of 40% to 45% – far higher than any other treatment at the time or since.

Pain relief

Elsewhere, studies of people with terminal cancer showed that LSD therapy could relieve severe pain, improve quality of life and alleviate the fear of death.

In the United States, the CIA tried giving LSD to unsuspecting members of the public to see whether it would make them give up secrets.

Meanwhile, at Harvard University, Timothy Leary – encouraged by, among others, the beat poet Allen Ginsberg – gave it to artists and writers, who would then describe their experiences. When rumours spread that he was giving drugs to students, law-enforcement officials started investigating and the university warned students against taking the drug. Leary took the opportunity to preach about the drug’s power as an aid to spiritual development, and was soon sacked from Harvard, which further fuelled his and the drug’s notoriety. The scandal had caught the eye of the press and soon the whole country had heard of LSD.

By 1962, Sandoz was cutting back on its distribution of LSD, the result of restrictions on experimental drug use brought on by an altogether different drug scandal: birth defects linked to the morning-sickness drug thalidomide. Paradoxically, the restrictions coincided with an increase in LSD’s availability – the formula was not difficult or expensive to obtain, and those who were determined could synthesise it with moderate difficulty and in great amounts.

Negative reputation

Still, moral panic about its effects on young minds was rife. The authorities were also worried about LSD’s association with the counterculture movement and the spread of anti-authoritarian views. Calls for a nationwide ban soon followed, and many psychiatrists stopped using LSD as its negative reputation grew.

One of many stories in the press told of Stephen Kessler, who murdered his mother-in-law and claimed afterwards that he didn’t remember what he’d done as he was “flying on LSD”. In the trial, it emerged that he had taken LSD a month earlier but at the time of the murder was intoxicated only with alcohol and sleeping pills. Yet millions believed that LSD had turned him into a killer.

Another report told of college students who went blind after staring at the sun on LSD.

Two US Senate subcommittees held in 1966 heard from doctors who claimed that LSD caused psychosis and “the loss of all cultural values”, as well as from LSD supporters such as Leary and Senator Robert Kennedy, whose wife Ethel was said to have undergone LSD therapy.

“Perhaps to some extent we have lost sight of the fact that it can be very, very helpful in our society if used properly,” said Kennedy, challenging the Food and Drug Administration for shutting down LSD research programmes.

Possession of LSD was made illegal in the United Kingdom in 1966 and in the US in 1968. Experimental use by researchers was still possible with licences, but with the stigma attached to the drug’s legal status, these became extremely hard to get.

Research ground to a halt, but illegal recreational use carried on.

Friederke Meckel, a psychotherapist who uses LSD alongside conventional talk therapy.

Friederke Meckel, a psychotherapist who uses LSD alongside conventional talk therapy.

At the age of 40, after 21 years of marriage, Friederike fell in love with another man. Sadly, he was using her to get out of his own marriage. “I had a pain within myself with this man having left me, with my husband whom I couldn’t connect to,” she says. “It was just like I was out of myself.”

Her solution was to become a psychotherapist. She says she never thought of going into therapy herself, which in 1980s West Germany was reserved for only the most serious conditions. Besides which, her upbringing taught her to do things herself rather than seek help.

Friederike was at the time working as an occupational physician. She recognised that many of her patients’ problems were rooted in difficulties with their employers, colleagues or families. “I came to the conclusion that everything they were having trouble with was connected to relationship issues,” she says.

A former professor of hers recommended she try a technique called holotropic breathwork. Developed by Stanislav Grof, one of the pioneers of LSD psychotherapy, this is a way to induce altered states of consciousness through accelerated and deeper breathing. Grof had developed it in response to bans on LSD use around the world. Over three years, travelling back and forth to the US, Friederike underwent training with Grof as a holotropic breathwork facilitator. At the end of it, Grof encouraged her to try psychedelics.

Little blue pills

In the last seminar, a colleague gave her two little blue pills as a gift. When she got back to Germany, Friederike shared one of the blue pills with her friend Konrad, who later became her husband.

She says she felt herself lifted by a wave and thrown on to a white beach, able to access parts of her psyche that were off limits before. “The first experience was breathtaking for me,” she says. “I only thought: ‘That’s it. I can see things.’ And I started feeling. That was, for me, unbelievable.”

The pills were MDMA, a drug that entered the spotlight in 1976 when US chemist Alexander ‘Sasha’ Shulgin rediscovered it 62 years after it was patented by Merck and then forgotten. Upon taking it, Shulgin noted feelings of “pure euphoria” and “solid inner strength”, and felt he could “talk about deep or personal subjects with special clarity”.

He introduced it to his friend Leo Zeff, a retired psychotherapist who had worked with LSD and believed the obligation to help patients took priority over the law. Zeff had continued to work with LSD secretly after its prohibition. MDMA’s potential brought Zeff out of retirement.

He travelled around the US and Europe to instruct therapists on MDMA therapy. He called it Adam because it put the patient into a primordial state of innocence.

Controlled substance

MDMA was made illegal in the UK by a 1977 ruling that put the entire chemical family in the most tightly controlled category: class A. In the US, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), set up by Richard Nixon in 1973, declared a temporary ban in 1985.

At a hearing to decide its permanent status, the judge recommended that it should be placed in schedule three, which would allow use by therapists. But the DEA overruled the judge’s decision and put MDMA in schedule one, the most restrictive category. Under US influence, the United Nations Commission on Narcotic Drugs gave MDMA a similar classification under international law (though an expert committee formed by the World Health Organisation argued that such severe restrictions were not warranted).

Schedule one substances are permitted to be used in research under the UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances. In Britain and the US, researchers and their institutions must apply for special licences. These are expensive to obtain, and finding manufacturers that will supply controlled drugs is difficult.

But in Switzerland, which at the time was not a signatory to the convention, a small group of psychiatrists persuaded the government to permit the use of LSD and MDMA in therapy. From 1985 until the mid-1990s, licensed therapists were permitted to give the drugs to any patients, to train other therapists in using the drugs, and to take them themselves, with little oversight.

Psycholytic therapy

Believing that MDMA might help her gain a deeper understanding of her own problems, Friederike applied for a place on a “psycholytic therapy” course in Switzerland. In 1992, she and Konrad were accepted into a training group run by a licensed therapist named Samuel Widmer.

The course took place on weekends every three months at Widmer’s house in Solothurn, a town west of Zurich. Central to the training was taking the substances a number of times, 12 altogether, to get to know their effects and to go through a process of self-exploration.

Friederike says the drug experiences showed her how her whole life had been coloured by the loss of her father at the age of five and the hardship of growing up in postwar West Germany.

“I can detect relations, interconnections between things that I couldn’t see before,” she says of her experiences with MDMA. “I could look at difficult experiences in my life without getting right away thrown into them again. I could, for example, see a traumatic experience but not connect to the horrible feeling of the moment. I knew it was a horrible thing, and I could feel that I have had fear but I didn’t feel the fear.”

The second part of this series on psychedelic psychiatry will be published next week. Read it to find out what happened to Friederike Meckel Fischer after her arrest. This story was originally published by Mosaic at mosaicscience.com/story/psychedelic-therapy