Military veteran Nkutsoeu Motsau

Military veteran Nkutsoeu Motsau is still a defiant man.

Confined to an uncomfortable new bed and an unsuitable wheelchair, he continues to fight for the underdog.

The former Robben Island prisoner survived the apartheid regime and a horrific car crash years ago, which left him quadriplegic.

But he considers himself better off than most military veterans, who are living in hope that a string of government promises will change their lives for the better.

Affectionately known as “Skaap”, Motsau is chairperson of the Azanla Military Veterans Association, which represents about 2 500 former Azapo soldiers. They are among about 70 000 military veterans who are due benefits such as housing, pensions and medical care.

This is stipulated in the Military Veterans Act of 2011.

But five years on, many veterans are still struggling to get on to the official veterans database, without which they cannot get help.

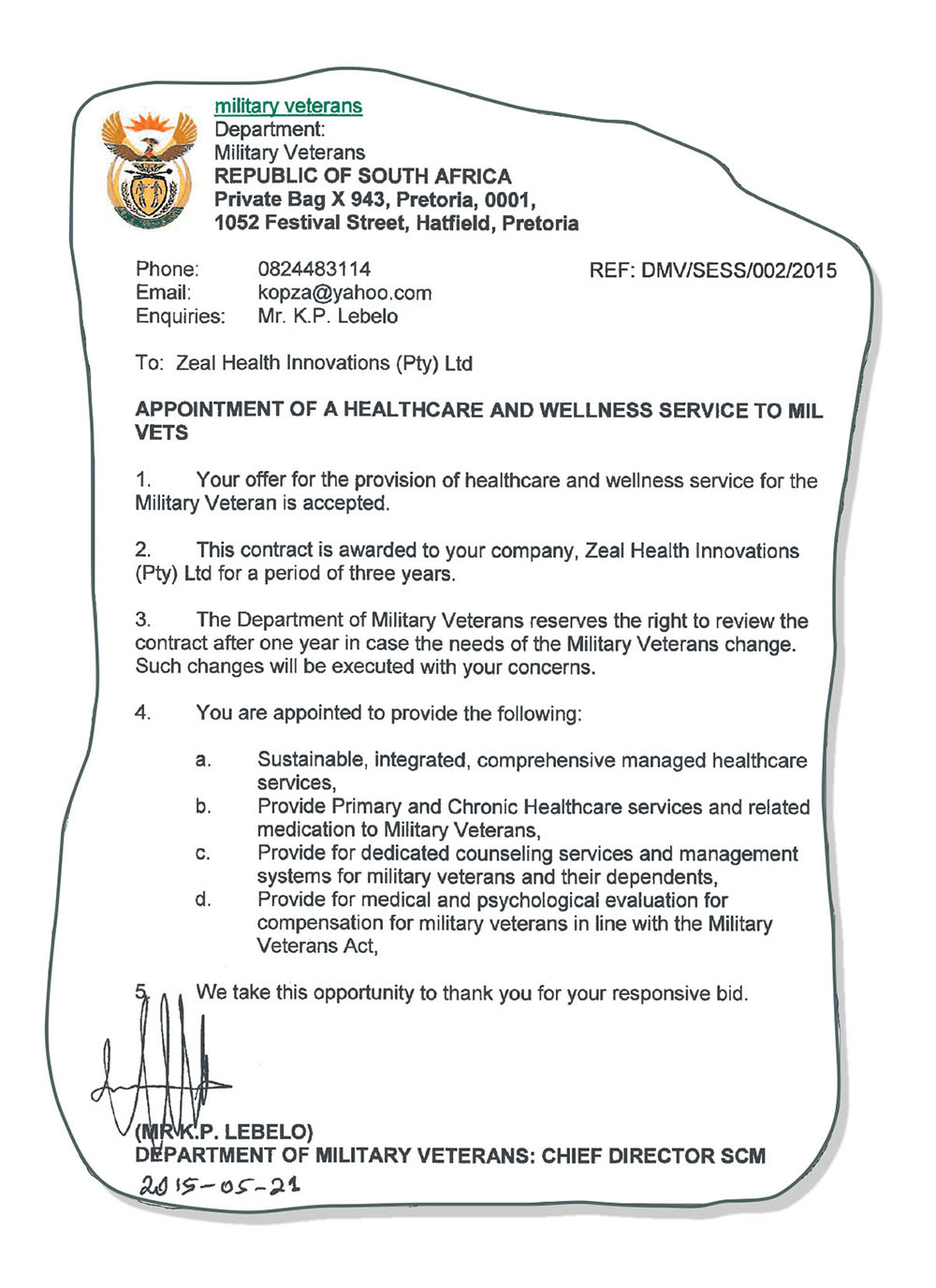

The department of defence and military veterans signed off on a multimillion-rand deal, in which a network of doctors, nurses, social workers and psychologists would provide basic healthcare services, including counselling for those with mental illness or suffering from post-traumatic stress.

But a court battle over the validity of the contract, signed off by senior department staff last year, means Motsau has had to pay R3?500 a month for a caregiver, who he cannot do without.

“They only paid her for one month. Thereafter, I had to pay for her out of my pension,” said the 62-year-old from his Khulani Park home in Khayelitsha, Cape Town.

Payment of this service was suspended when the department challenged the validity of a R200-million contract its officials signed with Zeal Health Innovations last year. Court papers state there wasn’t a budget for it, but the parliamentary select committee on public finances flagged more than R75-million in underspending over the past two years.

The department of military veterans, in response to questions, said it would immediately intervene in Motsau’s case. It does facilitate home-based care for those veterans in need.

The department’s spokesperson, Mbulelo Musi, said there are roughly 70 000 registered military veterans in the country who all qualify for access to free healthcare and just over 14 500 of those are indeed being provided with healthcare and wellness support currently.

Although he confirmed budgetary constraints, Musi said the department had allocated an additional R50-million to boost healthcare for military veterans in the new financial year.

The department introduced its “turnaround strategic support initiative” in September to ensure that veterans get access to housing, education and healthcare as soon as they are registered.

Motsau said his gripes about the type of mattress and wheelchair he has been given by the department pale in comparison to what other veterans have to endure.

“My friend in QwaQwa has cancer and he has had to pay out of his own pocket for his treatment since he was diagnosed. When the doctors give him a prescription, he has to find the money to pay for the medication himself,” Motsau said.

His friend, Charles Mokhatle, said he was diagnosed with the disease in 2014 and will finally start treatment at the Tempe military hospital next month.

Until now, he has paid thousands of rands to cover his medical bills. “I have the receipts and hope the department will pay me back,” said the 66-year-old Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) veteran on Tuesday.

He also has to make the 340km trip from his home to Bloemfontein when he needs to see a doctor. “If I had a medical card, I could just go to the nearest doctor,” he said.

The majority of military veterans receive healthcare at the country’s three military hospitals – in Bloemfontein, Pretoria and Cape Town – or at army base sick bays.

Qualifying veterans are meant to be given a medical card loaded with money so they can seek treatment close to home.

At least one former South African Defence Force soldier, who lives in northern KwaZulu-Natal, said he was registered as a military veteran in 2012, but he has received no benefit other than a medical card.

“So far, there has never been money loaded on that card. When I go to a doctor, they tell me there is no money in there.

“Fortunately, I do not have major health problems, but some of my friends, they do,” said the former soldier.

The plight of the military veterans is well documented, but a more worrying problem is what is deemed a system of “gatekeeping”.

“The problem appears to affect mostly those veterans who fought at home, as opposed to those who operated in camps in exile,” said Faizel Moosa, the treasurer of the MK Military Veterans Association in the Western Cape.

A panel investigates and verifies former soldiers’ credentials, after which they are placed on a national database, which then gives them access to the benefits.

Moosa said he has had personal experience of this during his verification process. He told the panel that he had worked in MK structures under Johnny Issel.

“Those on the panel had never heard of him. Who among those involved in politics can say they have never heard of Johnny?” Moosa asked.

Issel, who died in 2011, was a former MK commander, one of the founding members of the United Democratic Front and a trade unionist.