A pig’s carcass lies in a cage at a secret location on the Cape Flats. Weather-monitoring equipment is attached to the cage.

“Our human rights have been trampled on.”

“The bread price has rocketed.”

“Corruption and the corrupt run rampant.”

“Fight for our right to our land.”

“We are tired of our taxes being plundered.”

And “South Africa is an incarnation of Animal Farm today”.

All of this, everything, is President Jacob Zuma’s fault. So says speaker after speaker at the People’s Assembly march, which gathered at the Gauteng legislature on Wednesday.

Born less than a month ago on the steps of the Constitutional Court, the People’s Assembly vowed to “paint Zuma black” on Freedom Day with demonstrations in Durban, Cape Town and Johannesburg.

The gathering on the steps of the legislature in downtown Johannesburg struggles to muster a crowd beyond 300 people waving #ZumaMustFall posters.

The movement has likened itself to the iconic gathering in Kliptown more than 60 years ago, when the Congress of the People gathered from all corners of South Africa in front of a general dealer’s stoep.

History documents that thousands of South Africans recorded their demands in what would ultimately inform the Freedom Charter. “A good coat, because winters are cold,” wrote one attendee on the slips of paper handed out all those years ago.

On Freedom Day, the museum that tells much of the story of this historic event is closed.

At the Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication in Kliptown, Soweto, where the charter is laid out in bronze, there are no people.

Stanley Wauchope is disillusioned that freedom has not come to Kliptown. (Photos: Delwyn Verasamy, M&G)

A group of tourists arrives and stares into the conical brick tower at the centre of the square, intently reading the document.

Just off the pristine square, peeping through openings in the wall, hawkers jostle to sell their trinkets and wares.

“Hey! Bring them here. They must buy our stuff,” one implores the tour guide.

Volunteer and activist Vusumuzi Ngcobo describes the charter as a list of wishes that thousands of dispossessed black people wanted achieved in the country in 1955. Today, for many in his community, it is still a mere wish list.

“Many black people don’t know about their past and this place is supposed to open their minds, but they do not make use of it. And that is also understandable, as you can easily see that their lives haven’t changed much. The Freedom Charter represented the wishes of our forefathers but they remain exactly that – wishes,” he says.

His tone changes as he looks at the manicured gardens and a beggar, sniffing glue, approaches him for money. “One question we must ask is: Have the wishes of that Freedom Charter been fulfilled?”

Kliptown’s Walter Sisulu Square was largely deserted on Freedom Day.

Right there, next to the monument honouring the founding document of the Constitution, lauded as the most progressive in the world, freedom has a totally different meaning.

On the lawns a teenager, who would only give her name as Portia, said she had no idea why the square had been built, or how she would get through her tertiary years. She wants to be a mechanical engineer.

Not far from the entrance to the square’s conference centre – which, according to residents, is too expensive for them to hire – stallholder Patrick Moreware sits resignedly under a tree.

“This holiday is just making my life difficult because I have no customers today,” he says.

He points to the squalor of the area; people are jobless and live in shacks.

“I don’t think that was what freedom was for,” he says.

Nearby, where a bridge carries you aross over the rumbling trains, the hundreds of rusted tin roofs are disturbed only by the dusty gravel roads weaving through shacks and homes that have been there for decades.

People on that side of the tracks don’t believe freedom has arrived.

Stanley Bobby Wauchope sits next to his elderly brother. He is tired of this life.

“The charter had a very significant role to play, but most of those rights have not been implemented. To me, I see no importance of celebrating this day. My own brother died for the struggle and here we are in this shantytown and no one cares,” he says.

He adds that he no longer has the energy to attend events commemorating Freedom Day because he believes that, at least on his side of the train tracks, freedom hadn’t arrived.

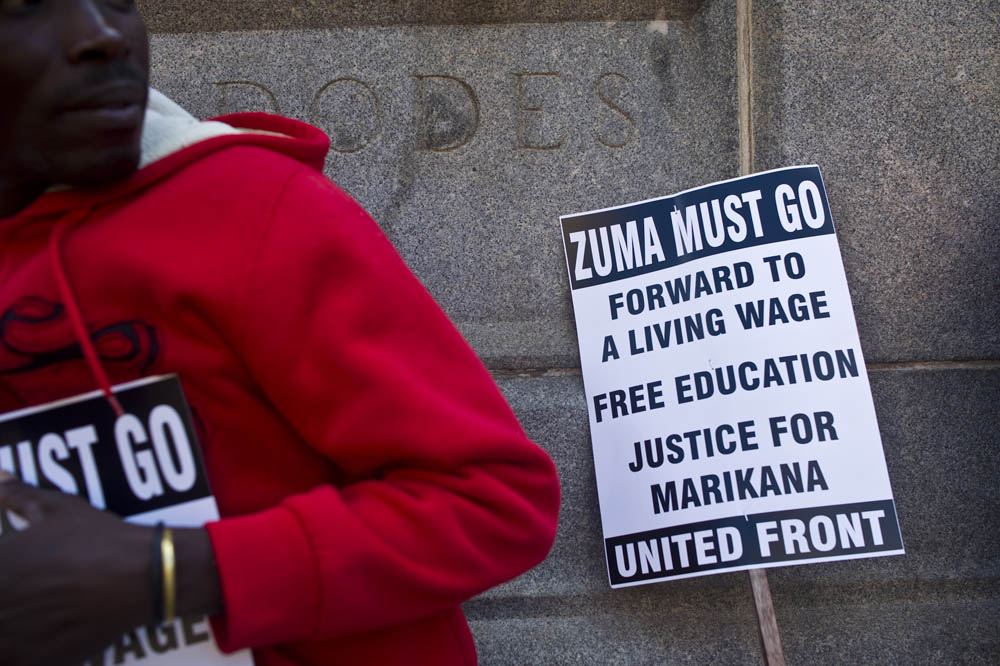

In Johannesburg central, a contingent of civil society protesters once again called for President Jacob Zuma to be axed.

Back up Chris Hani Road, 15 minutes along the M1 and through the ghost town that Johannesburg’s centre becomes on public holidays, the marchers at the legislature are insistent they will be a part of the change they want to see. At the heart of their unrealised freedom is corruption under the current leadership, they say.

Peter Sithole from Midrand says he felt it was time for him to be part of something, especially during these concerning times.

“We have drifted so far away from the charter; it’s painful to see that people are still poor [and that] there are no jobs or proper healthcare.”

Sithole adds that he was concerned that some people were not participating and more needed to be done to open up spaces for gatherings such as this.

“In the beginning it is very hard to get people going, especially if there is not a voice around a movement, but I know people are interested in the change,” he says.

“Speak to anyone and they will tell you that they want change – and that’s what we are here for today.”