In 1908, South Africa became the first African nation to participate officially in the modern summer Olympics. But four years before Durban-born athlete Reggie Walker became the first African to win Olympic gold with his surprise show of speed in the 100-yard dash in London, a ragtag group of South African men informally participated in the 1904 St Louis Olympics.

The first Africans to participate in the modern Olympics were not remarkable athletes like Ethiopia’s Abebe Bikila, who won the 1960 Olympic marathon in Rome, becoming the first black African to win an Olympic gold. Instead, they were battle-hardened soldiers – Boer commandos proficient in horse riding and guerrilla warfare, machine gunners in the British imperial forces, and Tswana dispatch runners, all of them brought to St Louis by the imperative to earn a living after a protracted war of attrition.

On March 1 1904, two years after the end of the South African War (1899-1902), an advert appeared in Johannesburg’s Rand Daily Mail. “Boer War Exhibition,” it declared. “A chance for the unemployed! £4 per month and deductions.”

The takers for this United States-bound spectacle, spearheaded by a Canadian scout who had served with the British during the recent war, included two Tswana men, Len Taunyane and Jan Mashiane. History now remembers them, sort of, as the first Africans to compete in the Olympic marathon.

The bid to host the 1904 summer Olympics was originally won by Chicago. This did not sit well with powerbrokers in St Louis, a rival industrial powerhouse, which, in 1901, began work on a large-scale exposition linked to the centennial of the 1803 Louisiana Purchase Treaty. Using threats and bullying, St Louis eventually secured hosting rights for the nascent sports spectacle.

In the manner of today’s city-branding projects, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition was a self-aggrandising affair. “City visions of glamorous growth danced before the eyes of St Louis boosters,” writes American historian James Primm.

The $20-million project saw the Native American mounds in Forest Park flattened to make way for the summer-long spectacle, which was pitched to audiences as a “university of the future”. The original fair grounds now constitute a landscaped park and are a short drive south from Ferguson, a flashpoint of contemporary racism in the US.

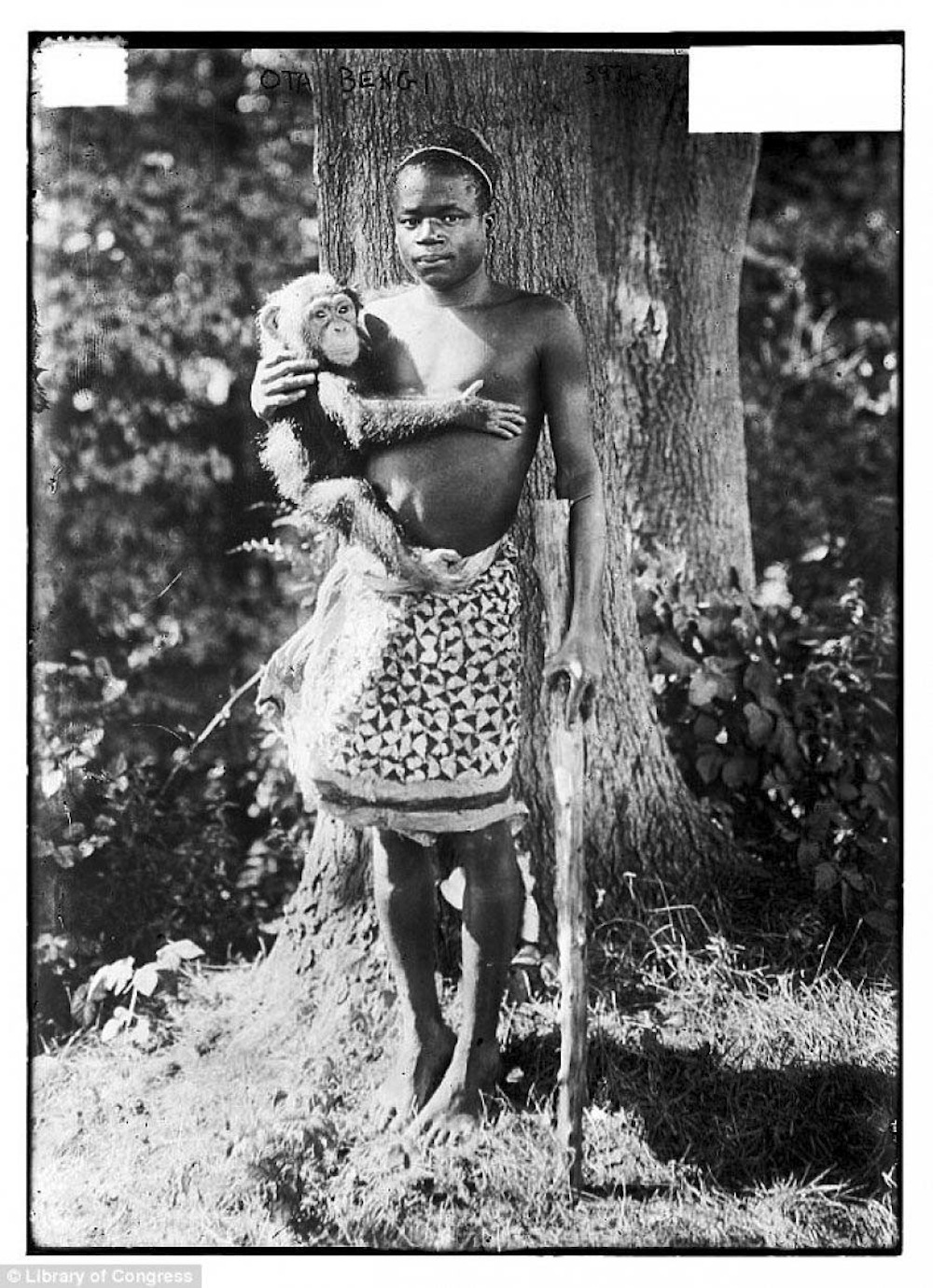

Ferguson is not irrelevant given what happened in St Louis a century earlier. The displays at the 1904 world’s fair ranged from the fascinating to the strange, but often verged into the outrageous. The skeleton of a large whale aside, the fair included a recreation of an Inuit village, complete with tents and huskies. The latter formed part of what historian James Gilbert calls a “living tableaux” of cultures that included Filipinos, Patagonians, Ainu people from Japan and Ota Benga, a Mbuti pygmy man from the Congo (who was later exhibited in the Bronx Zoo).

Ota Benga, a Mbuti pygmy from the Congo, was part of a ‘living tableau’ at the 1904 fair and was later housed in the Bronx zoo.

“Native villages were arranged in ascending order of race and cultural progress, capped with a demonstration of American efforts at inducing general progress through a model school,” writes Gilbert in his 2009 book, Whose Fair?.

South Africa was represented in this human circus by men who signed up to re-enact key scenes from the South African War. They included two real-life Boer generals, Benjamin Viljoen and Piet A Cronje, and demobilised soldiers from both sides.

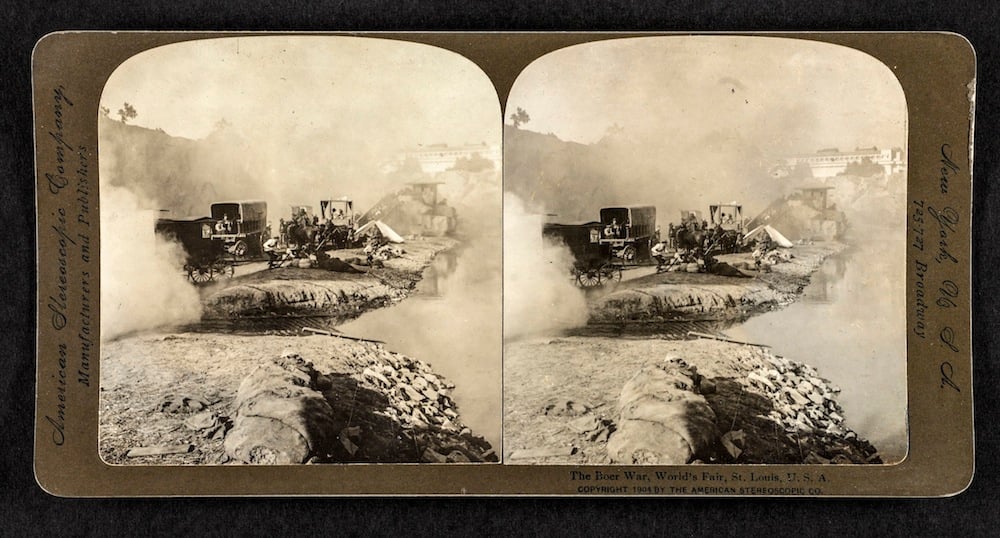

Conceived by AW Lewis, an artillery captain with battle experience in the war, the spectacle was given artistic credibility by the involvement of South African circus impresario Frank Fillis. The show, which was performed twice daily and included ample explosions, reprised two key battles, Colenso and Paardeberg, the former a Boer victory.

The programme also included displays of swordsmanship, circus acts, musical shows and horse racing in a purpose-built pavilion with a small river and seating for 15 000 visitors. Cost of entry: 50c.

Billed as “the greatest and most realistic military spectacle known in the history of the world”, the concession opened on June??17 1904. The scale of the enterprise is recalled in numbers: the day before opening, 600 performers from the “Boer War spectacle,” as it was known, participated in a street procession through St Louis.

The performers included two future Hollywood heavyweights: JP McGowan, an Australian-born diamond prospector who fought with the British and pioneer of the railroad action genre, and William Boyd, a circus “rough rider”, who later achieved fame for his role as cowboy Hopalong Cassidy.

The street procession also included 50 women in wagons and ox carts, two brass bands and a contingent of black South Africans in traditional dress. The latter included Mashiane and Taunyane, who many decades later were identified only as despatch runners. For many of the South Africans in St Louis, the performance of their identities came to define who they were, at least in the eyes of gullible spectators.

Mashiane and Taunyane first garnered notice during a two-day event organised by the fair’s department of anthropology. These “Anthropology Days”, as they were billed, were intended to test “startling rumours and statements that were made in relation to the speed, stamina and strength” of “several savage tribes”, to quote its organisers.

To this end, men in native costumes threw spears for the amusement of white men in bowlers and boaters. Benga and several of his countrymen participated in a mud fight. The aim of these displays of athletic ability was not singly for white amusement but also intended to vindicate white athletic ability and intellectual progress.

A news summary in the St Louis Post-Dispatch suggests the intellectual compass of this crackpot university on the plains of the Midwest: “Barbarians meet in athletic games; Pygmies in mud fight, pelted each other until one side was put to rout. Crow Indian won mile run; Negritos captured pole-climbing event and Patagonians beat Syrians in tug-of-war.”

Although the fair’s chief anthropologist, William McGee, felt vindicated by what he described at the time as the “utter lack of athletic ability on the part of the savages”, Taunyane nonetheless caught the eye of Olympic organisers. The taller of the two unremembered marathon runners, Taunyane was placed third in the “intertribal” marathon behind men from Syria and India.

On Tuesday, August 30, a hot summer day, both he and Mashiane were invited to participate in the Olympic marathon. The invitation was by no means philanthropic. Despite its ostentatious styling, St Louis was an unattractive destination for competitive athletes. Few foreigner competitors travelled from Europe to compete.

“Except our own athletes, practically nobody came except some Canadians, two Greeks and Felix Carvajal, the quaint little marathon runner from Havana,” recalled a New York Times reporter in 1932 of the marathon event he had witnessed. His recollection ignores the presence of three South Africans in the race.

RW Harris, from Aliwal North, was described in the local St Louis press as “the best long-distance runner of the country from which he hails”. Harris, however, dropped out of the Olympic marathon shortly after the halfway mark.

Mashiane and Taunyane, who ran barefoot and were described as Zulu men, both completed the race, which was a far from orthodox affair. Held on a hilly course, its dusty roads used by cars, the marathon’s route enabled one participant to hitch a ride in a car for a quarter of the race.

Thomas Hicks, a doped-up Briton running for the United States, eventually won the race. Strychnine cocktails and brandy shots did the trick.

Carvajal, a former mail carrier who had lost all his money in a crap game in New Orleans and hitchhiked to St Louis, might have done better had he not eaten some green apples from an orchard en route. He is reported to have got “a stomach ache” and finished fourth.

Mashiane could have done far better had he not been chased off course by a dog. A newsman with the St Louis Daily Globe-Democrat reported on the incident. He mistakenly identified Mashiane as “Lentauw” (Taunyane), whose Tswana surname is a compound: tau denotes a lion. Perhaps their names were simply switched to allow the journalist to indulge in some purple prose.

“The ‘Lion’ was cavorting wildly across a stubble field, after the manner of the original African cakewalker, with a plain yellow cur of an American watchdog running a close second, with prospects of a speedy union between the cavernous display of canine molars and the rearmost portion of the ‘lion’s’ garments,” reported the bemused journalist.

Both Tswana athletes had their names butchered by reporters struggling to render their far-away names phonetically. Taunyane, who placed ninth, is variously named as “Leentonro”, “Letorew”, “Letouw”, “Leentouw” and “Leetouw”. Mashiane, who came twelfth, is quoted as “Yamasina”, “Yamasani”, “Yamasaria” and “Yamasini”.

War games: The re-enactment of the battles of Colenso and Paardeberg were a great hit at the Louisiana Purchare Exposition of 1904.

Writing in a 1999 edition of the Journal of Olympic History, Stellenbosch University sport historian Floris van der Merwe first restored a modicum of dignity to these unremembered men. Van der Merwe was researching the history of sport in prisoner-of-war and concentration camps during the South African War when he came across the story of Mashiane and Taunyane. He later travelled to St Louis where he found a photograph of the two runners at the Missouri Historical Society.

Van der Merwe, whose 1998 book The Boer War Show of St Louis is an important reference, is not the first writer to find profit in this weird fragment of South African history. American playwright Eugene O’Neill, in his 1946 Broadway play The Iceman Cometh, set in a New York flophouse, revisits this history through his down-at-heel characters General Piet Wetjoen and Jimmy Tomorrow, a former South African War correspondent.

More recently, novelist Sonja Loots has repurposed this history in fiction. Her novel, Sirkusboere (2011), is partly set in St Louis and includes a black character. Jan Windvoël (Fenyang), a support rider, straddles a difficult position between collaboration and self-fulfilment in the novel.

It is hard to know whether Mashiane and Taunyane were haunted by similar dilemmas. Their voices are entirely absent from history.

During the run of the South African War circus, a group of black participants “escaped” from the circus encampment. They were later “captured” in a black neighbourhood in St Louis. Lester Walton, a prominent black journalist and later US diplomat in Liberia, reported on the incident.

“The negroes had visited their untutored brethren in their huts and kraals in the Boer War camp,” he wrote at the time. “They learned that they were being held as prisoners. They thought that, if they assisted their South African relations to escape, they would only be exemplifying the doctrine of the emancipation proclamation.”

In her 2008 biography on Walton, Colored Memories, historian Susan Curtis tells that the circumstances of the black South Africans in St Louis “stirred memories of their own struggle” among African-Americans, who had been railroaded into endorsing the outlandish fair project. Moved by their plight, some African-Americans offered food to eat and places to stay, even jobs so that they could set themselves up independently.

Curtis also quotes Walton as writing that local African-Americans were “very much excited over the holding in bondage of their brethren by the Boer War concession, and another attempt at their liberation would not be unexpected”.

Walton also quoted the South African Boer War Exhibition Company’s ominous response: “The Boer officer states, however, that hereafter the savages will be constantly under heavy armed guard, both night and day.”

The noisy Boer circus continued to intrigue and delight white audiences in St Louis until December 1. Loud action-driven entertainment aside, the appeal of the exhibit owed a great deal to its ideological basis.

Framed as a “libretto” in which two white warring nations are eventually able to reconcile, the programme keyed into a familiar post-Civil War theme of estrangement and reconciliation, a dynamic theme that glorified conviction, bravery and whiteness – “without having to consider what their struggle meant to men and women over whose land they fought”, adds Curtis.

The moment captured: A single photograph is proof that Len Taunyane and Jan Mashiane took part in the 1904 Olympic marathon.

After its successful run in St Louis, the circus headed for Kansas City. In January 1905, after a layover in Chicago, it moved to New York, where it settled in a suburban development in Coney Island. Recognising profit in the mixing of entertainment and suburban landscaping – think Canal Walk in Cape Town or Mall of Africa in Midrand – promoter William A Brady’s Brighton Beach Development Company underwrote the spectacle. The show was a hit.

“Twice a day,” reported the New York Times in May 1905, “rain or shine, an understudy for [General] de Wet makes his marvellous escape through a cordon of 50 000, more or less, British soldiers, while the multitude cheers, just as it will again cheer a few moments later when fickle fortune has transferred the good fortune of war to the other side … It is not an unpleasant way, this, to enjoy a conflict; not too exciting; not the least bit dangerous, and very, very noisy.”

But public interest soon waned and, in late 1905, a court-appointed sheriff seized the costly spectacle. One of the show’s big names, 69-year-old General Piet Cronje, had sued to recover an unpaid salary of $2 429.

Cronje, who had surrendered his troops at the Battle of Paardeberg, was a disgraced figure in his homeland. Showmanship was a final play for this defeated man. With the South African War spectacle shuttered, he swallowed his pride and returned to South Africa, where he is today remembered as a “circus Boer”.

Others reverted to what they knew best: opportunist enterprise and war. McGowan ended up in Hollywood, whereas Ben Viljoen, the other general, founded a Boer colony in Chamberino, New Mexico. US president Theodore Roosevelt personally aided in the resettlement.

Sympathy for the Boers was relatively widespread in the US at the time, where they were likened – sometimes unfavourably, notably by black journalists – to Southerners, although there was a political agenda to enabling Viljoen. The smallest of the many Boer diasporas, Viljoen’s settlement formed part of a political play by Roosevelt’s government to expand US territory in the New Mexico border region.

In 1911, a year before New Mexico became part of the US, Viljoen fought in the Mexican Revolution, on the side of wealthy landowner and future Mexican president Francisco Madero González. The force of pro-Madero “foreign legionaries” also included the grandson of Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Garibaldi and AW Lewis, the man who had originally hatched the idea of a travelling Boer circus.

But nothing is known of the fates of Len Tau and Jan Mashiane. Were they, as Van der Merwe speculates, farm labourers employed by Cronje? Or, equally possible, did they decide – like Ota Benga – to stay in the US? Perhaps they were part of the troupe of “thoroughly traditional rural-traditional dancers” left stranded by choreographer Frank Fillis in New York, as is detailed in a 1915 letter to liberal politician WP Schreiner? Who knows?

The subjective experiences of these two athletes is intriguing. What were their thoughts about the florid neoclassicism of the newly emergent American empire being staged in St Louis? Did they meet Geronimo, the Bedonkohe Apache leader who was invited to the fair and allowed to sell photographs of himself in an ill-fitting suit for 25c? What did they say among themselves about the dizzying verticality of Chicago and New York? History is silent about these questions.

There was no heroic welcome for Taunyane and Mashiane, only the imprecise accolades and belated redress of historians. As it stands, the singular and divided lives of Len Taunyane and Jan Mashiane possess the certainty of rough pencil sketches. But there is that photo.

It attests that, long ago, two men wearing cut-off trousers and the numbers 35 and 36 pinned to their shirts entered a running race. That photo, that proof beyond words, is a fragile archive against forgetting. It affirms what cannot be fully told in words.

Sean O’Toole is a journalist and co-editor of Cityscapes, where a version of this essay first appeared