'Without fundamentally improving the accessibility of high-quality education to those from the poorest households, the fourth industrial revolution will continue to reproduce inequality,' writes Hamadziripi Tamukamoyo. (David Harrison/ M&G)

The lead researcher for an important international study has red-flagged the drop in the number of grade nines who excel at maths, pointing to its potential effect on the county’s future thought leadership and economy.

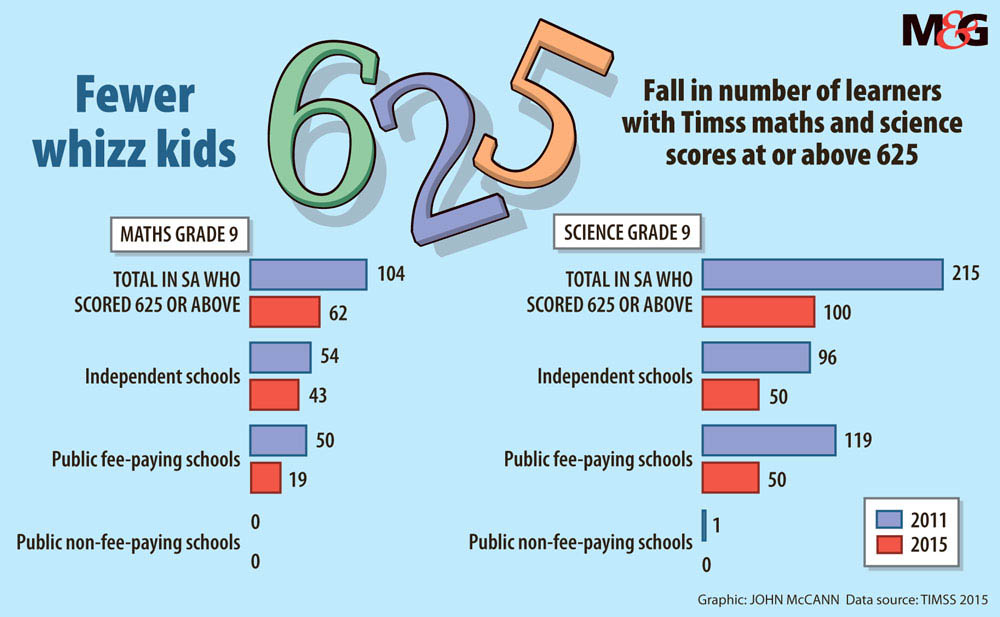

The number of grade nine maths whizz kids fell to 62 last year from 104 in 2011, one of the unsettling findings to emerge from a comparison of statistics of high-fliers who participated in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Timss) in 2011 and 2015.

The decrease in mathematical boffins is “a red flag”, says Vijay Reddy, the Human Sciences Research Council’s chief researcher in the Timss. “We absolutely need these people [top performers] for thought leadership and to grow the economy.”

Reddy says that the Department of Science and Technology’s National System of Innovation (NSI) was dependent on a group of high-fliers.

” … if we want to maintain our NSI we will have to import skills; we will have to attract people from outside the country to take on those responsibilities. Our NSI would wither away and we would lose a group of thought leaders.

If the group of high-fliers gets too small, they would start leaving the country to work with bigger groups of like-minded people.”

Reddy says that an intervention is imperative. “South Africa has committed to a high skills economy and it is critical that there is a programme to support and extend high performers so that the country continues to have learners scoring at the advanced benchmarks.”

She said the percentages rather than the numbers “tell a truer story” but that in all cases there was a drop.

The number of learners who scored above 625 points at private schools decreased to 43 last year from 54 in 2011 and to 19 from 50 at former Model C schools. A score above 625 points places a learner in the advanced category. None of the grade nine maths learners from no-fee schools achieved this milestone in either 2011 or 2015.

While 5% of learners globally scored above 625 points, only 1% of South African pupils managed to achieve this feat.

Despite the decline in the number of top performers nationally, Reddy was upbeat about their performance because none of the other low-performing countries had learners featuring in the advanced category.

South Africa’s grade nines were ranked last out of 39 countries in maths in last year’s edition of Timss.

“Many countries have programmes to nurture and extend their top learners. We do not have such programmes in South Africa and the DBE [department of basic education] understandably has focused on the lowest performing schools.”

The department of science and technology has a talent development programme for high-fliers that is run by the University of the Witwatersrand, but Reddy says it is a small programme.

“Investment and support for high-performing students could assist in pulling the whole system to better performance.”

She said high-performing pupils would migrate to independent and fee-paying schools because this is where they would be challenged by other learners and receive better teaching and learning environments.

Professor Jill Adler, who holds the South African Research Chairs Initiative chair of mathematics education at Wits University, said the top 5% of pupils internationally “are not likely to be from the relatively poor inner-city schools in New York or from the inner-city schools in inner London or from the rural schools in India”.

“The fact that we are improving slowly is important,” she said.

“Yes, we started from a low base and systems, whether they are on a low base or not, move extraordinarily slowly. It doesn’t matter what the system is, you don’t get huge quick changes in systems.”

Adler said it was known that there was an 80:20 divide in the country, where 20% of learners have access to fully functional, well-performing schools.

“Our well-performing kids are coming from those schools by and large so the Timss reflects that rather than contradicts it. It’s miraculous there’s even a percentage coming out of no-fee schools. We’ve got real talent in our no-fee schools; the Timss shows us that they’re there.”

At least 141 maths learners in grade five scored above 625 points, including 85 from independent schools, 55 from former Model C schools and one from a no-fee paying school.

Vasu Govender, the president of the Association for Mathematics Education of South Africa (Amesa), says some of the world’s top maths pupils came from South Africa.

He questioned whether the normal maths teaching in schools was sufficient preparation for Timss.

“Do schools take Timss seriously? We are very exam-driven in South Africa and the fact that Timss does not count for passing or failing may mean that it was not taken seriously. I am confident that we can do much better in Timss as we have the mathematical talent in this country to do so.”

He said a key success in education was parental involvement, adding: “It would appear that parental involvement is lacking at many schools, more especially at no-fee schools.”

Aarnout Brombacher, a materials developer and researcher in the field of maths education, said it was disconcerting that fee-paying schools were not producing a large number of learners in the advanced category.

“If the hypothesis is that paying school fees improves your results dramatically, then the Timss results are not demonstrating that.”

Commenting on the number of top performers from private schools, he said: “It’s a little bit better but it’s not dramatically better. It’s not like sending your kids to a private school and ensuring that they suddenly perform from the poorest in the world to the best in the world. They actually just perform slightly better, so you have to ask yourself the question whether all of that investment is worth it.

“None of these results should surprise us because the consistent message coming through is the issue of the foundation phase. Children are getting into grade five and grade nine with foundations that are so weak that they can’t build on it.”

On the issue of the department of basic education’s recent controversial move to condone learners in grades seven to nine who passed all their other subjects but did not meet the 40% pass requirement in maths, he said: “If in grade nine you are getting 20% for maths, believe me, two more years of grade nine and you will still be getting 20%.” He attributed this to learners’ “very weak” foundational knowledge in maths.

“Unless we take you back three or four or five years and we take two or three years to build you up, you’ve got no hope. So these children are lost to the system. Why delay them [by failing them] for another year of trauma?”