NEWS ANALYSIS

The question of whether South Africa should allow land expropriation without compensation has re-emerged amid other furious debates over state capture, “white monopoly capital” and radical economic transformation.

The message from national leaders has been particularly mixed, most notably after President Jacob Zuma backed the notion of expropriation without compensation in a recent address to traditional leaders.

The ANC announced this week it would hold a special national executive committee (NEC) meeting to address the land question and find ways to identify “areas which are an impediment to effective and speedy land redistribution”.

But what would some of the practical realities be of introducing expropriation without compensation?

Much would depend on how the state went about expropriation, and whether it would apply to all property, or particular classes of property, such as agricultural land, according to Theo Boshoff, the legal intelligence manager at the Agricultural Business Chamber.

Importantly, section 25 of the Constitution applies to all forms of property, and if any type of property is expropriated, compensation has to be paid, said Boshoff.

If the state passed new legislation that provided for agricultural land to be expropriated without compensation, then it could be challenged on two grounds, he said.

First, all laws are subject to the Constitution and such an Act would presumably be at odds with section 25, which states that property may only be expropriated for a public purpose, or in the public interest, subject to compensation.

Second, it could constitute unfair discrimination on the grounds of occupation, which would violate section 9 of the Constitution, he said.

Section 9 prohibits unfair discrimination on several grounds, including compensation. If legislation seeking to introduce expropriation without compensation applied only to agricultural land and left all other forms of property untouched then it “may discriminate towards agriculturalists versus other professions”, he argued.

If section 25 itself was amended so that expropriation did not require compensation, then all forms of property, including land, immovable assets and intellectual property, would also be affected, he said. This would “open a Pandora’s box”, because the state would be able to take all kinds of property without compensation, he said.

The wider ramifications for the country’s financial system notwithstanding, an important question to consider is what would happen to the outstanding debt on land, specifically on farmland, and what this would mean for state institutions such as the Land Bank as well as the commercial banks.

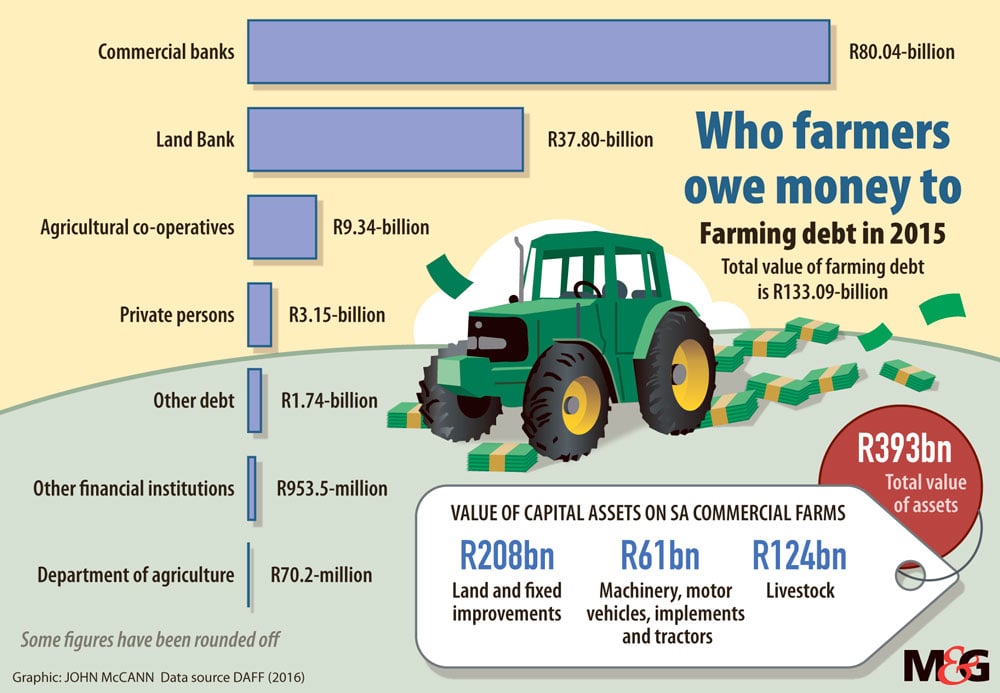

According to the most recent statistics from the department of agriculture, forestry and fisheries, as of December 31 2015, total farming debt was more than R133-billion. About R38-billion of this is held by the Land Bank, R80-billion is with commercial banks and about R9.3-billion is held by agricultural co-operatives.

The debt-to-asset ratio in the agricultural sector is extremely high and many loans are secured by registering mortgage bonds over the property, Boshoff said.

The rationale is that, if a farmer defaults, the land can be sold to recover the outstanding debt. If this collateral, the land, is expropriated without compensation, then it becomes an unsecured loan, he said. The farmer will have lost the land, his means of production, and will not be able to pay back the debt. Likewise the financial institution will not be able sell the land to recover the debt that the farmer cannot pay and, if the farm debt is written off, “it would spell disaster for financial institutions who have invested in the agricultural sector”, he said.

This would not only have huge negative consequences for the recovery of existing debt, said Boshoff, it would also discourage lending to the sector in the future because of the increased risk.

The Land Bank, according to its latest annual report, funds most of its lending by raising money on the open market by issuing instruments such as bonds. The bulk of this funding is not supported by government guarantees, which amount to only R5.5-billion.

The inability of the Land Bank to pay its bondholders would have serious consequences for the operation of the bank, which not only funds commercial farms but also emerging farmers. According to the annual report, slightly less than R1-billion has gone to support emerging farmers.

The agricultural debt owed to commercial banks is a fairly small proportion of the roughly R3.4-trillion in gross loans and advances the country’s four biggest banks had outstanding at the end of 2015.

But if section 25 was amended and expropriation of all kinds of property was allowed, it would “dramatically increase” the risk for lenders because the collateral could be taken away without compensation, he said. It would in effect mean that intellectual property, movables and all other forms of property could also be taken away with no compensation.

“This would substantially raise the risk of investing into South Africa and consequently have negative effects on investor confidence, which could be disastrous for the economy as a whole,” Boshoff said.

According to Ernst Janovsky, the head of Absa agribusiness, such a move could devastate the financial system, because banks would not be able to secure fixed assets as collateral against the credit they provide.

From an agricultural perspective, this could sink the agricultural system and threaten food security, he added.

Christie Viljoen, an economist for the advisory firm KPMG, said the problem with statements such as expropriation without compensation is that there is no intellectual exercise that looks at the practicalities of the proposals. This contributes to ongoing policy uncertainty and “that’s when people hold off on investment”, he said.

If the fundamentals of secure private property rights are tinkered with, this could have serious implications for the economy, Viljoen said.

Economic history has shown that secure private property ownership drives investment and economic development. As an example, domestic food production took a “big knock” after land invasions began in Zimbabwe, which is still heavily dependent on food imports from South Africa and elsewhere in the region, he said.

A question of constitutionality

The Constitution, under section 25, allows for expropriation of property for public purposes, or in the public interest, subject to compensation. The amount of money paid and the time and manner of the payment must be “just and equitable” and reflect a balance between the public interest and the interests of those affected.

But it also includes a number of “relevant circumstances” that must be considered, although these are not exhaustive. They are the current use of the property; the history of the acquisition and use of the property; the property’s market value; the extent of direct state investment and subsidy in the acquisition; beneficial capital improvement of the property; and the purpose of the expropriation.

The government’s efforts at land reform are included as being in the public interest and property is not limited to land alone.

To change any clause in chapter two, which covers property rights, a two-thirds majority is required in the National Assembly, and the supporting votes of at least six of the nine provinces in the National Council of Provinces.

The ANC at present does not have a two-thirds majority.