According to estimates

Laurens Schlebusch farms with crops and livestock in the Free State. Looking around his farmlands, he says the drought has almost certainly been broken.

He has just been driving through his crops of sunflower and maize. “Compared to last year, it looks much better. Our crops look good and the veld looks much better. We actually have veld for the cattle this year.”

In fact, the rain since Christmas has been so heavy that farmers have struggled to plant their lands because the ground has been too wet, said Schlebusch, who acts as Free State Agriculture’s regional representative for the Bloemfontein and larger Mangaung area.

But there has been no rain since the end of January and the farmers need more to finish off the season with a bang.

“There is potential on the field; we just need to complete that potential,” he said, adding that his maize crop could easily yield four tonnes per hectare if all goes well.

A decidedly wet start to the year has seen the Vaal Dam reach 100% capacity for the first time in several years. According to estimates, there could be a bumper maize crop — the largest in 36 years — and a record year for soybeans.

And it’s not just in his area. Agbiz agricultural economist Wandile Sihlobo said: “The drought, looking at it now, is pretty much over. In many regions there has been high rainfall and we are expecting a bumper year for many crops.”

Instead of dragging the economy down, agriculture could add 0.4% to gross domestic product this financial year, said Sihlobo. That would be R17.6-billion of the current R4.4-trillion GDP.

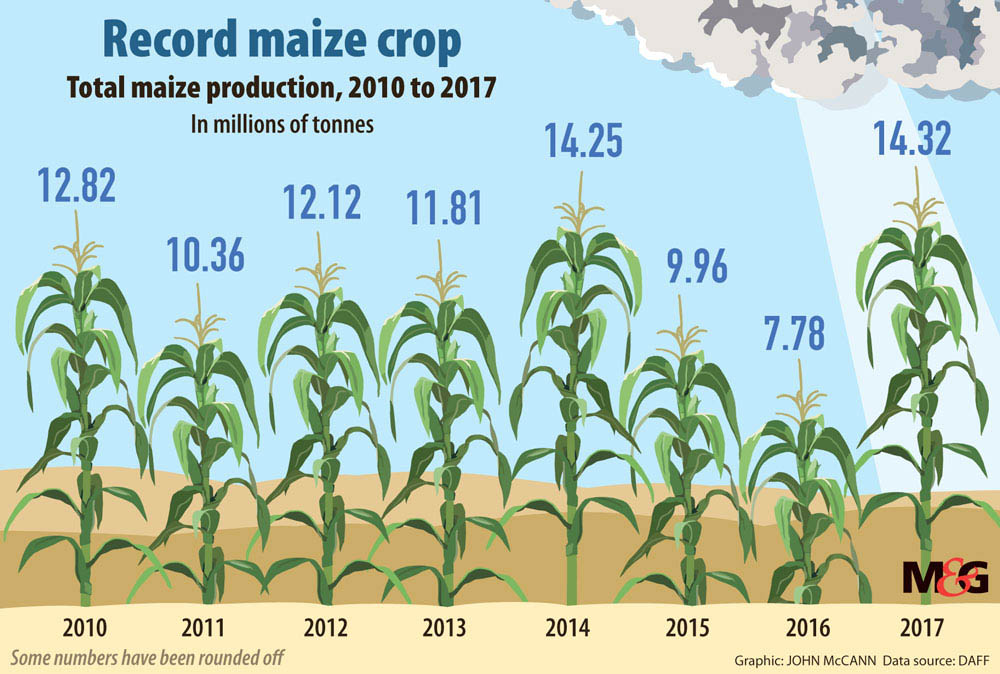

The crops estimates committee released revised forecasts last week and it expects maize production to almost double to 14.3-million tonnes this year from 7.7-million tonnes last year, which will make South Africa a net exporter again.

Soybeans are expected to reach the highest production level yet, with an estimated crop of 1.16-million tonnes compared with 742 000 tonnes last year. Sunflower production could increase to an expected 896 000 tonnes this year from 755 000 tonnes last year.

The area planted with soybeans was only slightly larger than last year, and the area planted with sunflowers was in fact smaller.

A good maize price at the end of 2016, especially for white maize, saw farmers planting a much larger area of maize than they did the previous season.

“By the time farmers planted, the price was still high. The higher price definitely drove it [the bumper crops],” said Dawie Maree, head of information and marketing at FNB business and agriculture, adding that a great deal of rested land could also have assisted in better crops.

“In a normal year, our maize trades halfway between import and export parity. If there is not enough, the crop will trade at a price higher than import parity. A bumper crop drops the price to export parity,” he said.

But now the prices are significantly lower.

“We all knew there would be better rains this season. But we did not foresee a price of R1 800 [a tonne],” said Schlebusch. “We thought R2 500”.

“Unfortunately, its supply and demand,” said Schlebusch. “I tell my wife I’m stupid I didn’t hedge, but that is easy to say,” he said, adding that selling ahead of time comes with its own risks: farmers are obliged to fill quotas regardless of the harvest. And farmers just don’t have the cash to take big risks now.

Jack Armour, the operations manager of Free State Agriculture, said the drought might have ended but the repercussions live on.

Farmers who diversified were better equipped to withstand the drought. Others were forced to sell less productive farms or nonproductive assets to keep them going until rain arrived.

Suppliers of seeds and other inputs even sold on credit to farmers, with easy terms, to assist them through the tough times.

Although the drought has seen some farmers go under, it was typically those who had bad debts for several years before that, Armour said. “It wasn’t the drought, but the drought was the last straw.”

The financial standing of farmers will take time to recover, said Sihlobo. Total farm debt was last estimated at R133-billion in 2015 and it is thought to have grown during the past year of drought and is likely to be closer to R160-billion now, Sihlobo said.

For those still standing, the road to recovery is going to be long. The main thing now is to generate cash flow so that farmers can get out of debt.

“For those that couldn’t plant or get a crop [last year], it means they had to wait a whole year to try again, without cash flow, or any income for that matter,” Armour said.

Planting can cost between R5 000 and R10 000 a hectare, he said, and the fixed costs, such as repayments on bonds and mechanisation loans, continued to rack up when there was no rain.

For crop farmers, it could take up to eight years to return to the financial position they were in before the drought, he said.

Certain livestock will take longer to recover, as will sugar crops, which may take three years, Sihlobo said.

But the drought is continuing in the Western Cape and Cape Town has less than 100 days of water left, with a real threat that taps could run dry. But it is a winter rainfall region and it is hoped there could be some relief as early as this month.

The area produces wheat, a winter crop and one of South Africa’s most economically important grains. It has a strong link to the food manufacturing industry, Sihlobo said.

The region exports apples, pears and other deciduous fruits, making it one of the bigger provinces for foreign exchange earnings, said Maree.

Now the fear is that another El Niño could be on the way. “Everyone is saying there is a 60% chance that, as of August, we could see another El Niño creeping in,” Sihlobo said.

Last week, the South African Weather Service’s chief forecaster, Eugene Poolman, said during a presentation to the National Disaster Management Advisory Forum that there is a likelihood of El Niño making a comeback in a few months’ time, towards spring. But it is still too early to predict, if it happens, what its impact might be on Southern Africa’s summer season.

Yet, he said, water in dams and groundwater has been replenished in most areas.

GMOs save the day for SA

South African farmers know how to farm in a crisis. They are equipped with varieties of maize that are drought- and pest-resistant through genetic modification.

It was because of GMO crops that the fall armyworm had such a fleeting effect on South Africa’s crops. “Everyone has heard of someone who had them, but no one has had them themselves,” said Wandile Sihlobo, an agricultural economist at Agbiz. “They didn’t affect much of our crop.”

The fall armyworm took hold in neighbouring countries and Zimbabwe is said to have escaped lightly when the pest decimated 10% of its crop. But 85% of the maize grown in South Africa is resistant to such pests.

Dawie Maree, the head of information and marketing at FNB business and agriculture, said the impact was negligible: there was some damage to soybean crops and one case in which 1% of the potato crop was lost.

He said another factor was that farmers thwarted the threat by being proactive and spraying the fields where the pest was detected.

Sihlobo agreed, adding that South Africa has a chemicals industry that can supply farmers’ needs.