(Rofhiwa Maneta)

Rofhiwa Maneta recently self-published Metanoia, his first book. It’s a collection of short stories that blur the line between fact and fiction, with mental illness as a recurring theme.

“I finished the book a few months after having something of a breakdown at work — multiple panic attacks — and seeing the people closest to me having breakdowns of their own,” says Maneta. About a year prior to this, three of his friends were admitted to psychiatric hospitals after they each suffered nervous breakdowns.

“Most of them just suffered in silence,” he says, “because as much as the internet would have you believe, mental illness is something people still think they have to deal with privately. The book was an examination into what happens when bad things happen to good people.”

In the first story, It’ll Be Better Tomorrow, Njabulo Khumalo, the story’s protagonist, is being admitted into Metanoia Psychiatric Clinic after suffering a series of panic attacks at work.

“One panic attack is fine,” says Khumalo. “We could all chalk it up to burnout; the result of a demanding work schedule. But breaking down at the office every other week — crying in the kitchen, shaking in front of a meeting — well, that’s just proof that I am not entirely in control of my mental faculties, not fit to work or function in my current state.”

The amount of detail in the stories hints at autobiographical elements. “I drew most of the events and narrative arcs in the book from my own experience,” says Maneta. “But I only did so because it was convenient; you can only write about what you know. But yes, I took real-life situations and personalised them for dramatic effect.”

In a story titled Can Themba, Zolani, a struggling writer, is months behind on his rent. His stories have been rejected three times in a week. He is living in a dump of a place in Observatory, Cape Town.

Maneta is quick to separate fiction from fact about Zolani’s experiences. “Me and the main character are similar in that we’re both writers who’ve had our work routinely rejected. We’re different in that the character is a neurotic, pill-popping alcoholic and I’m not.”

“Some stories, however, are completely true,” he continues. “I Don’t Make the Rules, for example, is a real-life conversation I had with a white friend who kept trying to justify why he should be allowed to use the n-word. A Better Calibre of Black is based on multiple experiences I’ve had at restaurants in Cape Town where my partner and I have been victims of racial abuse. So, I’d say it’s an equal split: half fact, half fiction.”

One way to look at the collection of stories is a snapshot of Maneta’s experience in Cape Town, where he now lives after leaving his home city, Johannesburg.

“Cape Town is a strange place to live in,” he says. “I moved here at the end of 2014 and it still takes some getting used to. For one, I don’t remember ever being called a kaffir while I lived in Johannesburg, and that’s happened here. There are also the racist rental practices to consider.”

Race and racism feature prominently in Metanoia, and Maneta grapples with these demons from many angles. In Thank You, My ANC and Don’t Assume, the characters in each story are fired from their jobs. In the first story, a young black man is hired by a white-owned company to produce content for young black urban youth. The website’s numbers aren’t impressive and, under pressure to increase engagement, the protagonist tweets a porn link via the company’s account. In Don’t Assume, the protagonist is fired for questioning an ad campaign that uses tired stereotypes targeted at black people.

Reading the collection, it’s not difficult to see the areas where art imitates life. Maneta even takes on the hot-button topic of men’s relationships to feminism.

In Dinner for Two, a man messes everything up while trying to prove he’s a “male feminist” during a date. He blurts out every term and phrase he’s ever seen on woke Twitter before security intervenes and throws him out of the restaurant. “Hyper-masculinity! Gender identity! We should all be feminists. Please, Lemonade! Beyoncé. Men are trash. Black men are trash. Black men are trash.”

It’s one of my favourite stories in the book — funny and edgy, and hits home. As men, we have so much learning and unlearning to do, and it comes with its own awkward moments.

Maneta himself is not immune to awkward moments and questionable statements. One that caught my attention was posted in April, when he tweeted: “Apparently women are the only human beings with nuanced, multifaceted personalities and men are monolithic douchebags that can be easily profiled. The current discussion re: men are trash operates under this very dynamic.”

After a short back-and-forth in the comments section with a friend, he retorted: “If this reads as a ‘not all men’, it points more to my failings as a writer than it does to my politics.”After being called out, he tweeted: “I’ve said some pretty despicable things about women. Reread some of my tweets. Realised I was the kind of man I always despised. Anyway, this isn’t a public performance of contrition. I should probably deal with my anxieties away from Twitter.”

I ask Maneta about this short-lived phase of his cyber-life, to which he responds: “I have said a few things I regret. Just hard to answer this without someone reading this thinking I advocate rape.”

I ask him if he has any reservations about the concept of feminism.

“Essentially I was talking about the theatre of male feminism (in Dinner for Two),” he says. “I’m talking about guys who’ve been outed on Twitter and Facebook; men who use the idiom of feminism to cloak their misogyny. Guys who quote bell hooks harp on about hyper-masculinity and patriarchy, only to be outed as abusers and misogynists in the future.

“Sometimes we forget: misogyny is an active decision. In as much as patriarchy is a social construction, I think we forget that every time a man cusses a woman out, rapes or murders her because she’s a woman, it’s an active decision. Men know they shouldn’t rape women, but they do. The story was basically an attempt at saying: [self-professing] feminist or not, men shouldn’t be trusted. Period.”

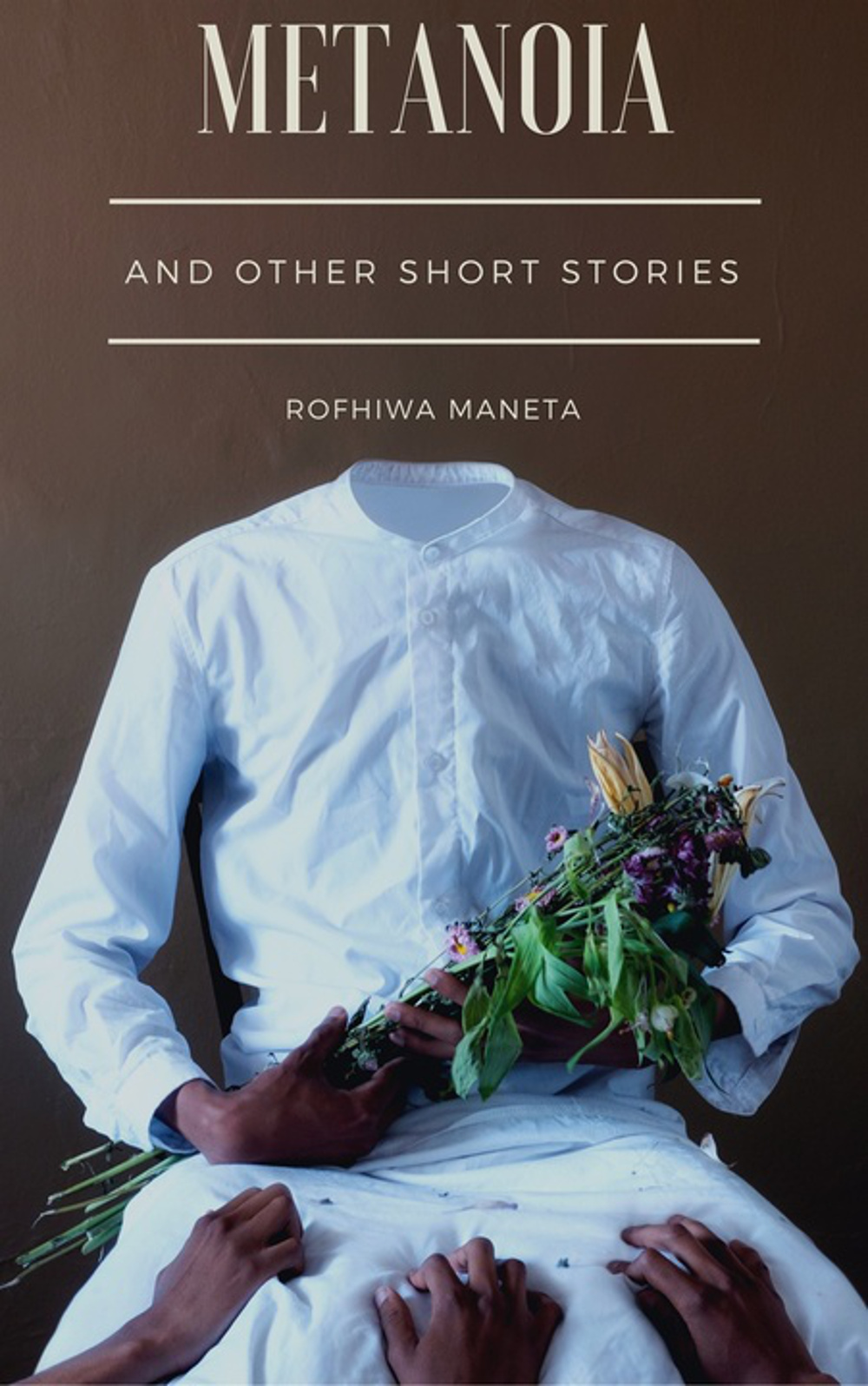

Even if men don’t deserve our trust, I can venture that Maneta’s writing skills do. His stories are short and straightforward, yet still descriptive. Working with photographer Andiswa Mkosi for the cover, and Tsoku Maela for the book’s special edition, Maneta has created a project with very little backing.

Metanoia is also accompanied by a short film, shot by Tseliso Monaheng, as well as a photobook entitled You’re Dead, based on one of the book’s stories.

“With the exception of Koleka Putuma’s poetry [published by uHlanga Press], I don’t remember any other mainstream publisher doing that,” Maneta says.

“Because of budgetary constraints,” he says, “I had to design the cover and work on the layout myself. So whatever shortcomings the book has, it wears on its sleeve.”

For the film, search for “Metanoia Short Film” on YouTube. On e-book and photobook, search for “Metanoia” and on mediafire.com search for “You’re Dead”