The cash reserves that South Africa’s largest firms are sitting on have soared in recent years, according to new research examining the investment decisions and strategies of the country’s major companies.

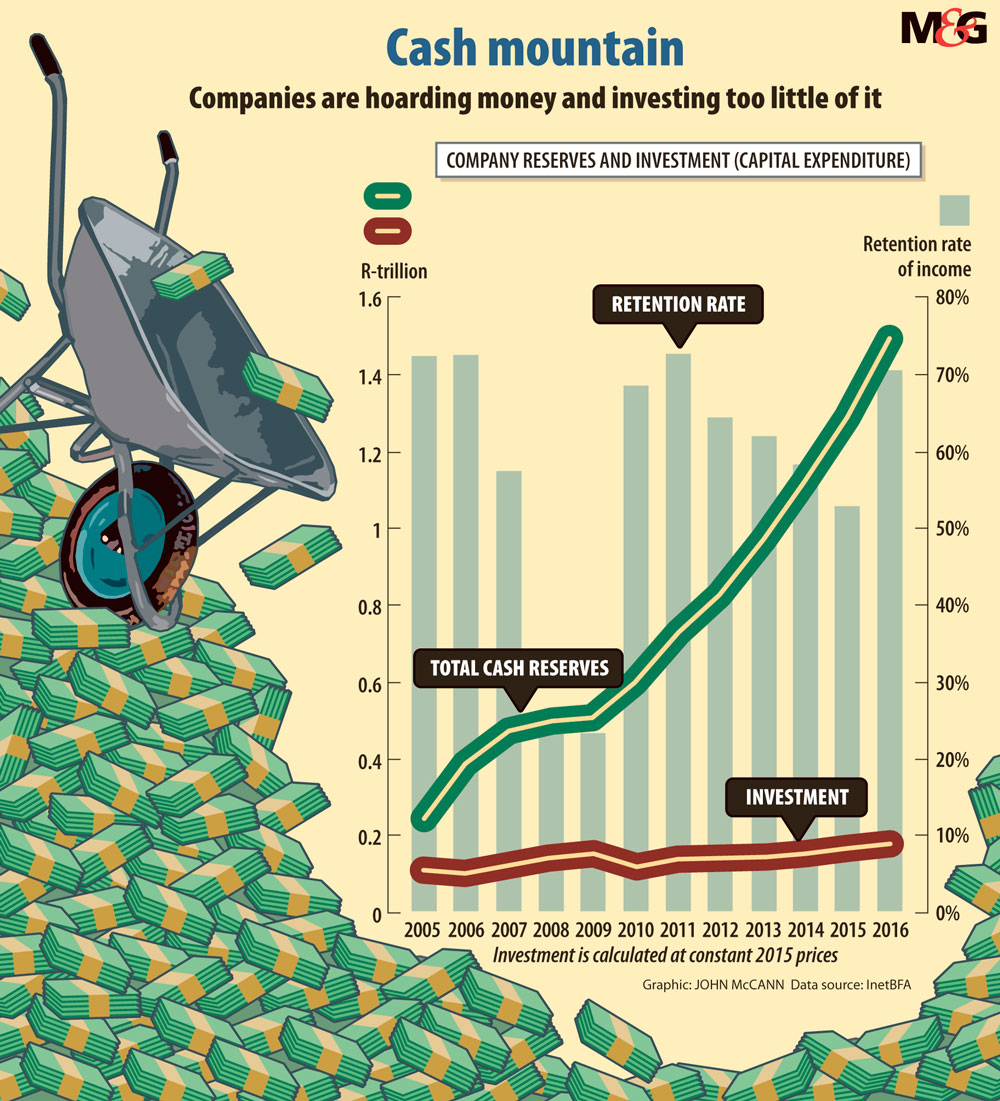

Accumulated profits or reserves held by the top 50 firms on the JSE have risen from R242‑billion in 2005 to R1.4‑trillion, according to work done by the Centre for Competition, Regulation and Economic Development.

This analysis, however, excludes some of the largest companies on the JSE that also have other listings on foreign stock exchanges and receive a large portion of their revenue from outside South Africa – such as British American Tobacco, Glencore and Naspers.

When including these firms, the figure is closer to R3.1‑trillion, according to a senior researcher at the centre, Thando Vilakazi, who formed part of a team of academics conducting the work on behalf of the department of trade and industry.

“Obviously, there are very legitimate reasons why firms choose to keep internal reserves,” Vilakazi said.

These may include internal policies, bids to hedge against risks and the clear issues linked to economic and political uncertainty, he said.

But there was a clear opportunity, he added, to unlock these reserves and to steer them towards reinvestment in South Africa.

The research comes at a time when low economic growth and political uncertainty have led to credit ratings downgrades, prompting questions about whether the private sector in South Africa has embarked on an investment strike. This has also coincided with calls for greater economic transformation of the economy.

The research found that although there has been some change in the composition of the top 50 firms listed on the JSE, major established firms still dominate the heights of the economy, despite some changes to company rankings.

The top 10 firms on the JSE – which represent about 58% of the stock exchange’s market capitalisation – are dominated by the firms with cross or dual listings that make the majority of their earnings outside of South Africa. They are British American Tobacco, SABMiller (which merged with AB InBev), Anglo American, Glencore, BHP Billiton, South32, Richemont and Naspers.

The researchers attempted to exclude these large internationalised firms in parts of their analysis, focusing on those that better illustrate company decision-making concerning industrial development in South Africa, the report said.

The work also reinforces evidence of the extent to which key economic sectors have high barriers to entry and are dominated by a number of entrenched firms.

Where there have been changes to the top 50, such as the emergence of large listed property groups, it was found that for the most part these firms did not have any significant operations locally. They are, in effect, “using the JSE platform as a source of capital for operations elsewhere”, the research noted.

“While this is a common feature of international capital markets, it is problematic in South Africa in the context of low domestic savings to fund investment, failures in financial markets – and banking in particular – in financing emerging industries and businesses, and a perceived and factual lack of finance and investment in general,” the research said.

The findings have implications for the ongoing debate about the ownership of the JSE by black South Africans.

Even though the emphasis tended to be on estimating the exact proportion of black ownership of the JSE, noted Vilakazi, it was even more important to consider the substance of that ownership.

“What really matters is that black South Africans own and operate productive assets domestically and that these companies can compete meaningfully and contribute to growth, investment and employment creation in South Africa,” he said. “The large internationalised entities are likely to account for a significant proportion of the foreign ownership recorded, and other shares may be held by pension funds and employee stock ownership plans such that direct ownership by black individuals may, in fact, be very limited overall.”

Although the most recent research did not interrogate this question further, it was an important consideration and an area for future research, he added.

Broadly, the country’s large firms, excluding the large internationalised firms, have been fairly profitable in recent years and have exhibited high retention rates – which illustrate the proportion of profits retained by a company. Despite this profitability, investment has been low.

The financial services, property, healthcare and consumer goods sectors were the main drivers of reserve accumulation, according to the research, with the banks contributing the most. Only three sectors – mining, telecommunications and consumer services – had retention rates of less than 50%.

But in the case of telecoms, this figure was skewed because of the Vodacom group’s policy of paying out 90% of profits as dividends. As the company does not have much debt and currently has a limited number of projects to invest in, it has taken the view that paying out dividends is the most efficient use of its cash, the research noted.

Between 2005 and 2009, there was a significant decrease in the amount of money contributed to reserves annually, while real investment by large firms increased.

The higher investment may be explained by firms’ increased spending relating to factors such as the 2010 World Cup, and reserves may have been used to fund this.

In addition, the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 may have affected reserve accumulation as companies faced economic pressure.

From 2010 onwards, both investment and the money contributed to reserves increased. But there was a clear gap indicating that firms were contributing more money to reserves than to investments.

“This may also have been significantly affected by greater caution exercised by firms in the years following the economic crisis, although this does not explain continued accumulation in later years,” the research found.

Where firms have been investing, the study observed that most were focusing more on capital expenditure aimed at maintaining current operations than on expansion. Here, however, the report did caution that data in this area was limited.

When excluding the large internationalised companies, the research found that most of the mergers and acquisitions in recent years, measured in terms of value, were taking place outside South Africa. On average, only 39% occurred locally between 2011 and 2016.

The research said that often such transactions do not represent an increase in real net wealth for the economy as a whole, although in some cases they may raise significant efficiencies. At the same time, mergers raise further questions about the increase in the concentration of the economy and the risk of anticompetitive behaviour.

Vilakazi said the polarisation of views between business and government is unhelpful and the solution to low investment lies in “recognising that each stakeholder has an important role and responsibility in addressing the current economic challenges”.

Firms are responsive to economic incentives and issues that affect the bottom line, particularly where costs can be cut, he said. In practice, this could include leveraging the existing incentive programmes that the trade and industry department already has in place, as well as encouraging investment domestically that includes black enterprises in the value and supply chains as a rule.

“Firms need to believe that government will follow through on its commitments, and vice versa, and putting in place appropriate conditionalities on the use of those incentives is critical,” he said.

Policy and regulatory tools needed to address industrial development, Vilakazi noted, adding that competition law needed to be strengthened to deal with anticompetitive conduct that undermines participation and investment by rival firms.

Banks stash their cash for good reason

On average, South African banks have contributed most to the cash reserves that the country’s top companies have accumulated in recent years. Between 2005 and 2016, this amounted to R25-billion, according to research by the Centre for Competition Regulation and Economic Development.

Although this could be explained by increases in liquidity requirements determined by regulations, this did not explain the growth of the reserves, the research noted.

Examining data from the South African Reserve Bank, it noted that loans for investments have remained stagnant relative to household loans and advances to different industries.

The findings point to broader concerns about banks’ slow lending to emerging firms, particularly black entrepreneurs.

The managing director of the Banking Association South Africa (Basa), Cas Coovadia, acknowledged that there were challenges, but that banks had lent more than R41-billion to black-owned small and medium enterprises between 2012 and 2015.

The sector faces increased regulation and emerging market challenges, including the reality that many South Africans have been interacting with the banking system in only the past two decades.

Coovadia said, these challenges aside, the new revised financial sector charter code identifies a “significant amount of money targeted towards black industrialists”.

South Africa needed to grow other areas such as its venture capital market to support black emerging businesses, he said. Venture capital, unlike the debt financing provided by banks, was longer term and venture capitalists could get directly involved in businesses.

Better co-ordination and co-operation was needed between government schemes meant to support black businesses and the private financial sector, Coovadia said, including identifying areas in the market that are not working.