(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

South Africa finds itself as neglected as the red-headed stepchild in a world market ravenous for higher-risk investment destinations.

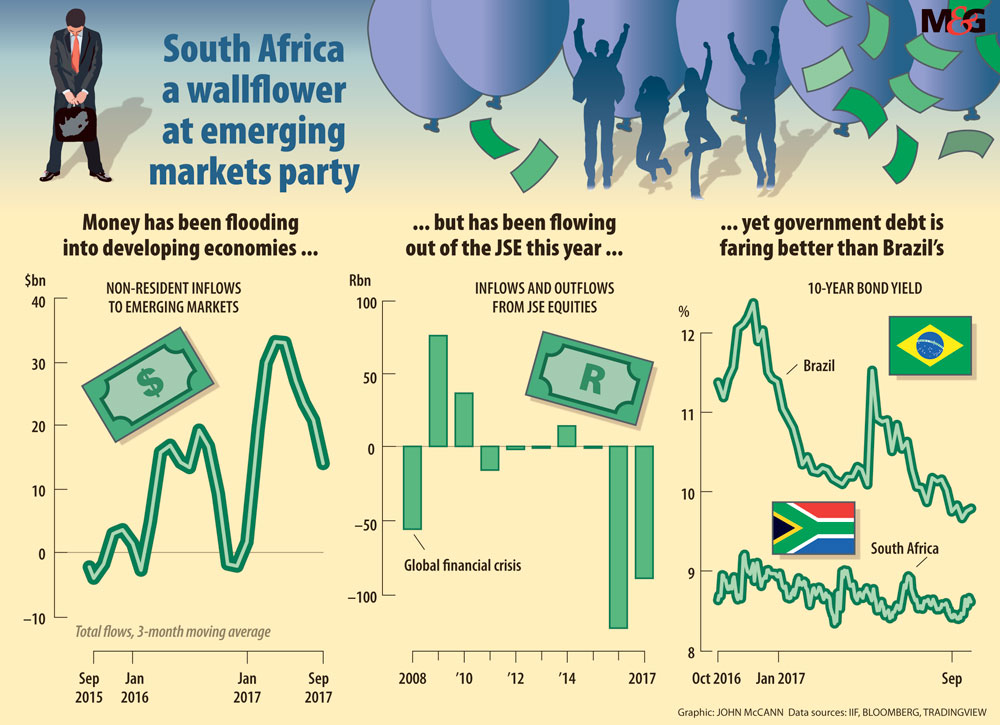

Although more than $1-trillion in foreign capital will flow into emerging markets this year, South Africa’s debt markets will benefit only marginally. And the outflows from South African equities in 2017 are likely to match, if not surpass, the record number — about R126-billion — that fled the stock exchange last year.

The search for yield globally means emerging markets are back in vogue. Capital inflows to these markets from foreign investors have rebounded to $1.1-trillion this year, according to the Institute of International Finance. Global risk appetite is at near post-crisis highs and growth is accelerating more quickly in emerging markets than in mature markets, according to the institute. Emerging market gross domestic product (GDP) has recovered to 4% from just 1.5% of GDP in 2015 — though this is still well below the pre-crisis peak of 9% GDP. Latin America will be the largest recipient of these inflows.

South Africa is benefiting somewhat from this. The government’s 10-year bond yield (the benchmark rate, which indicates a country’s cost of borrowing on the market) was at 8.6% this week.

But it could be better, as when it reached lows of 6% in 2013. And it could also be worse, as seen when it reached its highest level of 10.7% during 2008’s global financial crisis.

At the current level, South Africa is faring better than its peers Brazil and Turkey, which this week had 10-year bond yields of 9.8% and 10.7% respectively.

But India and Russia rank better, trading at 6.6% and 7.6% respectively. China’s 10-year yield was at 3.6% this week. Developed market 10-year bond yields are significantly lower — the United Kingdom’s is 1.3% and the United States’ 10-year treasuries are 2.3%.

Elena Ilkova, a Rand Merchant Bank credit analyst, said the way to assess whether a bond yield is good or bad is to look at how it has moved over time.

Ultimately, “the higher that number, the worse the opinion is of that issuer”, she said. A bond yield of 10% on South Africa’s 10-year sovereign is bad news, a yield of 7% is better news, Ilkova explained.

“The moment 8.6% is enough compensation for the risk, I [as the market] take that the government could default. If I change my opinion, I will demand a higher number.”

What will also drive moves in the sovereign bond yield is changes in the interest rate, Ilkova said.

Besides the yield, investors will look at a credit default swap (CDS) when deciding which emerging market to invest in. A CDS acts as a sort of insurance in the event of payment default. The price of a CDS is referred to as a spread.

Ilkova said there are no CDSes on South African rand-denominated bonds, which account for the bulk of South African debt in issue, but there are on dollar-denominated bonds.This is useful for investors who want to compare risk between countries.

“The most appropriate comparison is South Africa versus other emerging markets,” said Ilkova. When something happens globally, all emerging market CDS spreads are likely to move in the same direction. If investors are dumping emerging markets, for example, CDS spreads in these countries will move up across the board. But the spread is also affected by country-specific events.

Reezwana Sumad, a Nedbank Corporate and Investment Banking (CIB) fixed income analyst, said South Africa’s sovereign CDS spreads have spiked in recent weeks, “which means the cost of buying protection against a default has gone up”.

In a note published on September 13, Nedbank CIB said emerging market CDS spreads have been trending lower since 2016 because of easier global financial conditions. But, after Brazil, South Africa has the highest CDS spread relative to its emerging market peers.

This, Sumad said, is because of a great deal of political uncertainty and “a lot of event risk”.

Significant events include the ANC elective conference in December and credit rating reviews due before the end of the year.

Also, the dollar has strengthened relatively sharply thanks to a “hawkish” Federal Reserve, which has indicated its intent to normalise interest rates in the US, and a tax reform plan announced by US President Donald Trump, which proposes to cut the corporate tax rate from 35% to 20% and a once-off levy as an incentive to US multinationals to bring billions back into the US.

South Africa’s five-year CDS spread lingered around 190 basis points, according to Nedbank data. Brazil’s was slightly more than 200. Turkey’s was 188, Russia’s 152 and India’s 78.

Meanwhile, outflows from the JSE are on track to match last year’s record and have already reached R90.5-billion this year to date, according to Bloomberg. By comparison, net sales reached R56.6-billion in 2008 when emerging-market assets were sold off.

But Ilkova said one must differentiate between equity investors and debt investors. “What we have seen persistently for the past year, year-and-a-half, is that foreign investors are net sellers of equities. But this is not quite the case when it comes to bonds.”

She said foreign investors are buyers of South African bonds. In September, investors sold off R27-billion in equities but bought about R15-billion in bonds, she said.

“When it comes to equities, everything is about the expectations of the future. It is really about growth projections and the ability to earn future profits, so it’s not really a big surprise that investors don’t consider South African equities worth holding on to,” Ilkova said.

“When it comes to bond inflows, it’s about whether investors see relative value. That has more to do with relative comparisons with other emerging market sovereigns.”

But foreign inflows into the bond market are not all that positive. Sumad said the foreign holding of South African bonds has risen sharply in the past few months, which has prompted rating agency Moody’s to caution against these elevated holdings.

“It’s a measure of susceptibility,” Ilkova said, adding that, because foreigners hold 40% of rand-denominated bonds, it leaves South Africa vulnerable should there be a shock and foreign investors sell off.

It’s these inflows that are probably saving the treasury’s skin at a time when tax revenues are falling short.

The foreign holdings were bolstered when South Africa was included in a Citibank index, prompting a huge inflow of foreign investment into the market.

But credit rating downgrades, or an event that spooks the markets, could see these investors selling off suddenly and South Africa’s bond yields could quickly rise.

“It’s a double-edged sword,” said Sumad. “We need those inflows to finance the current account deficit but it poses a lot of external risks.”

According to a note from Nedbank’s CIB team, with South Africa now being rated sub-investment, it will take an unprecedented effort and willingness to steer the proverbial ship on a different course.

“Much depends on the MTBPS [medium-term budget policy statement], which should provide more clarity on the government’s fiscal path — a move away from the previous course could warrant a downgrade at either the November 2017 or June 2018 credit reviews.”