Economies of words: Nick Mulgrew’s fiction has become more assured

THE FIRST LAW OF SADNESS by Nick Mulgrew (David Philip Publishers)

‘Kip closed his eyes, seeking blankness for the smallest moment; but in the absence of light came a wave of sound, tinnitus filling his skull, roaring sea-foam and scum. The world, too full of colour, too possible.”

Durban-born Capetonian Nick Mulgrew’s latest collection of short stories, The First Law of Sadness, is a book full of the possible becoming probable, of the mundane made massive, of leviathans glimpsed out of the corner of an eye.

The quoted excerpt is from Jumper, a story that distils the typically South African psychological trait of viewing impending doom with both a cold sense of detachment and a panicked and under-rehearsed dread. The story is filled with the sense of being certain of calamity, while meeting it with farce; never knowing exactly which bomb will go off.

The lead character, Kip, finds himself in the throng of a parade for our victorious Springboks, and unwittingly becomes a witness to a man standing on a ledge outside of his apartment, threatening to jump. In the end (spoiler alert), the man does jump, but this is not a suicide. The man is a base-jumper, jumping as part of the celebration, the whole spectacle apparently staged.

In Jumper, Mulgrew manages to capture several aspects of white South African mentality in just a few short pages: the ridiculous use of violence and spectacle as entertainment, the impotent voices imploring him not to jump, the casual use of the word “bru”, and the eventual relief and normalisation of the spectacle as the show achieves its conclusion. Jumper muses on a twisted joke embraced by the public for the simple fact that it is not true.

It is this capturing of a white South African zeitgeist that Mulgrew does so masterfully. Perhaps this is what he set out to do with his first collection, Stations, an accomplished book that at times felt throttled by the overtly political. In his newest collection, however, his stories are given space to breathe. Here, Mulgrew’s scope of imagination is immense and, although some may find his positionality problematic, his clear depth of research and sensitivity lends his stories credence and his characters humanity, while providing us with something of a road map to empathy.

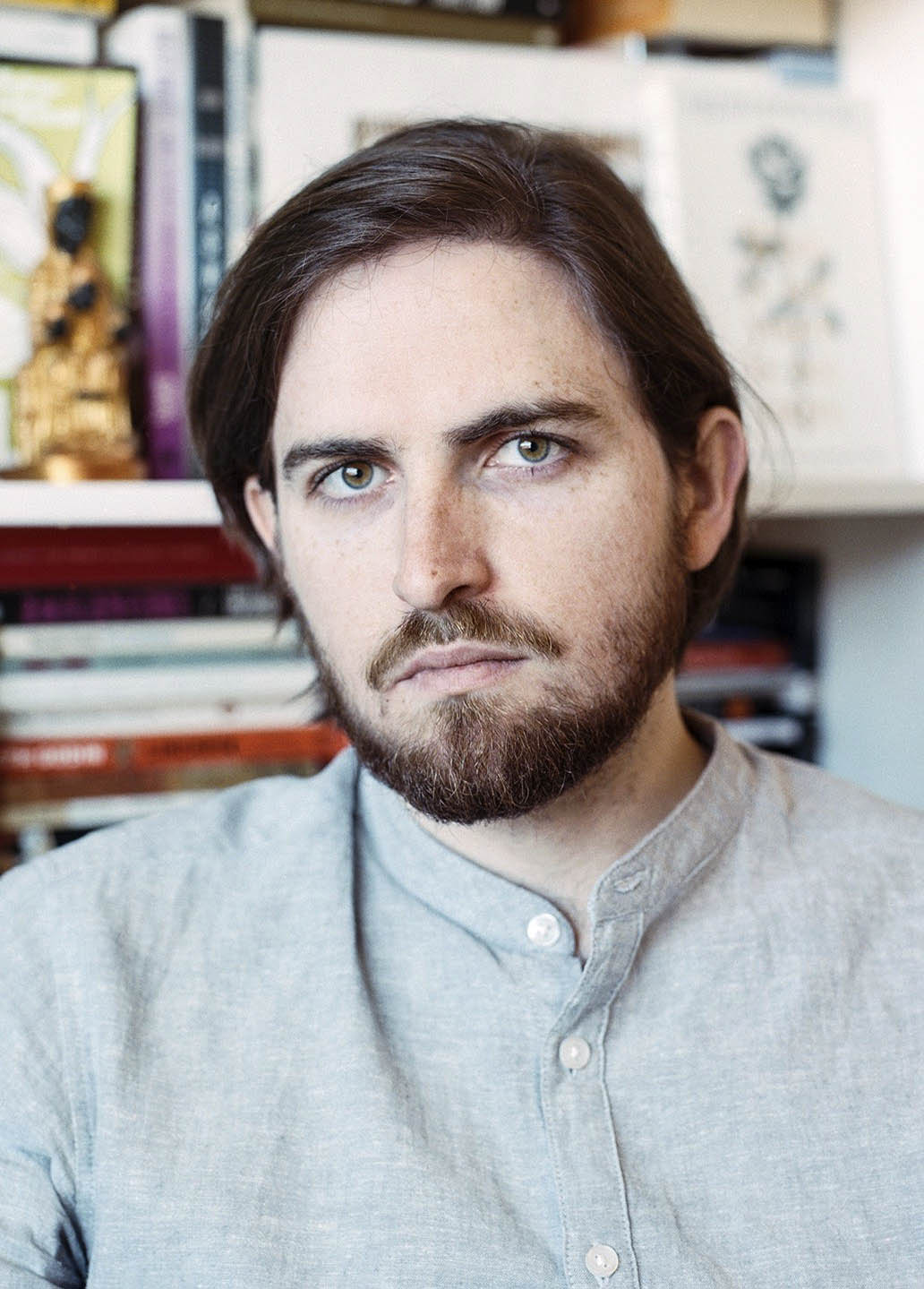

[Mulgrew writes his lived experiences (Michael Tymbios)]

Another of Mulgrew’s achievements is the protean ability of his voice and experimentation with modes of storytelling. One of the most tragic stories in the collection, For Sale: Set of Second Hand Mags for Toyota Corolla (mint condition), Bargain, is told through an ad placed online. One cannot help but be reminded of the six-word, flash fiction story, For Sale: Baby Shoes, Never Worn, often attributed to Hemingway.

This oblique form is an aspect that runs throughout Mulgrew’s fiction, with some of the most telling and poignant parts presented as asides or muffled voices overheard. For instance, in one of the collection’s stories, the spectre of white, male violence shows itself, as it so often does in reality, as a flippant remark. In The Turtle-Keeper, a white man, after hearing that infant turtles are often dug up on the beach for muti, responds: “Typical, hey. Muti.” This three-worded dismissal is a pinch that is easily recognised, holding far more weight than the small space it takes up on the page.

Mulgrew does well not to centre white privilege, choosing instead to have it feature as an omnipresent force, lurking menacingly in the corner, wielding its power but never taking centre-stage. It is this obscuring of power that gives his stories their force, allowing them to flourish with possibility.

The sense of the possible becoming probable is everywhere in The First Law of Sadness; from a foreign medical student landing up with a dead goat in the boot of his car at the home of an unknown interlocutor, to a woman skincare therapist who slowly turns into a torturer, the steps are all incremental, mundane even. The consequences, however, are drastic (aside from a certain airplane crash in Durban in the final story, which would be a deus ex machina had it not actually happened in reality).

This collection is certainly a maturation from what was already a strong debut, offering us an idea of what is possible for writers writing outside of their own lived experience. Through Mulgrew’s lens, we are opened up to a world which, like our Kip, becomes almost “too full of colour, too possible”.