Forget the white slimy stuff you may have seen your grandad eat; Florentine tripe is brown

The land is not just the dusty earth on which we stand. It is a kinship with our ancestors. It is an affirmation of self. It is the urgent aspiration for dignity and agency. This week the Mail & Guardian is proud to publish a story that is a continuation of a new, specialised reporting genre, focusing exclusively on the land, led by celebrated journalist Lucas Ledwaba

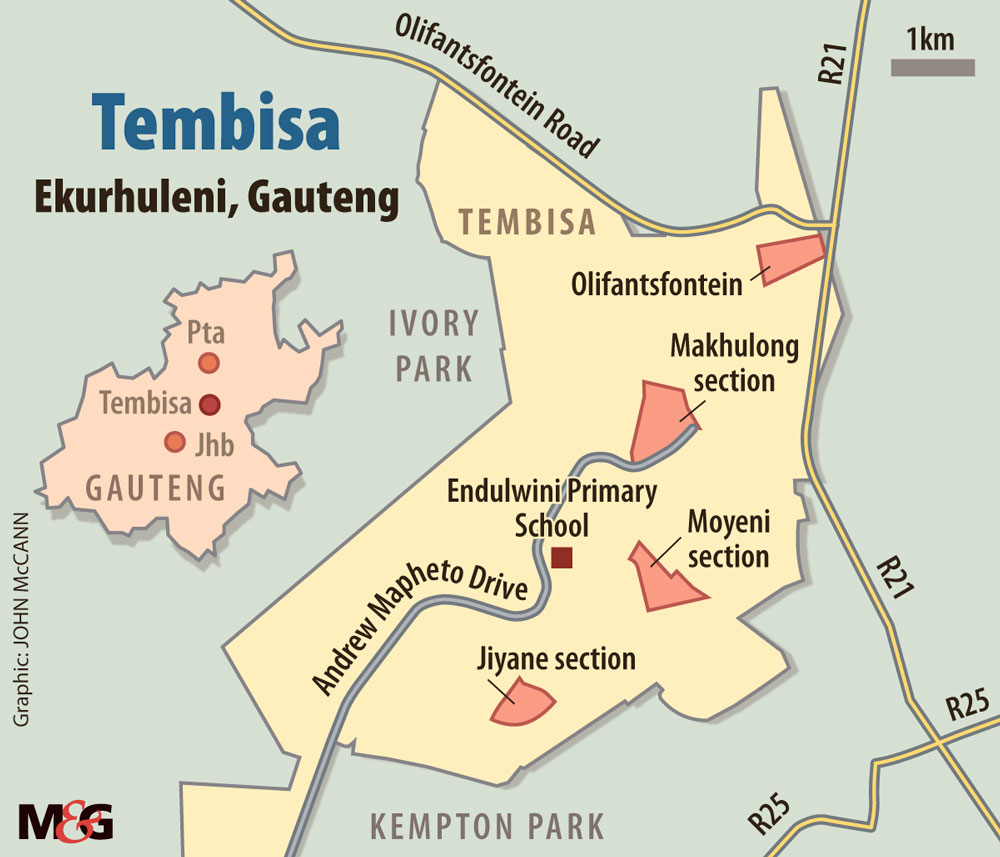

[Tembisa has a population of 463 109, which means many claimants can only get cash as compensation (John McCann)]

Amos Skhosana remembers a time, about 50 years ago, when his father brought him to the spot, now a grassy school playground, to perform ancestral rites at the graves of their forebears.

Then the graves were demarcated and built up with rocks that were clearly visible on the high ground above what is now Andrew Mapheto Drive, one of the busiest streets that connects Tembisa township to Kempton Park.

“My grandfather is buried here,” Skhosana points at the ground with a mixture of anxiety and confusion.

He looks around for signs of something, anything that bears testimony to the fact that a part of his heritage — his paternal grandfather Somkhambeni, his brother Koos and his maternal grandmother Mangisi Skhosana — lie buried here.

“Somewhere here. Somewhere here,” he says, carefully scanning the ground with bespectacled eyes.

The terrain doesn’t provide any hint of his forebears’ final resting place. Time and history have been unkind. The living have expunged any visible sign of their presence here.

This portion of the land that the Skhosanas once called home is now part of the Endulwini Primary School. Children in blue school uniforms run around here at break time, celebrating life, unaware of what lies in the ground beneath their little feet.

“The cattle kraal was here. My grandfather’s houses were over there,” Skhosana points across the road to vacant land overlooking row upon row of township matchbox houses, a church and the busy Andrew Mapheto Drive.

The Endulwini section of Tembisa was once farmland, where dispossessed Africans lived in some semblance of freedom as labour tenants on farms owned by their white conquerors. Because of colonial laws, they became tenants on the land they had once owned, for which they paid with their labour during certain periods of the farming cycle.

Skhosana does not know when exactly his forebears arrived here. But he knows that his grandfather Somkhambeni, who he believes was born in the 1800s, had his homestead right here. He remembers coming here with his father, around 1961, who told him about life here, about how they harvested watermelons and milked cows and worked the land.

Endulwini is now in the heart of Tembisa, a sprawling, vibrant, brawling, populous township 40km northeast of Johannesburg in the Ekurhuleni Metro.

In the last census in 2011, Statistics South Africa found that there were 463 109 people living in the township.

Sixty years old this year, Tembisa looks nothing like it did when his family was resettled here in 1964.

Skhosana was born in 1951 in Olifantsfontein, a settlement some 6km to the east of his grandfather Somkhambeni’s homestead. His father had moved to Olifantsfontein — forced to leave after a dispute with the farm owner. But 1950s South Africa was chaotic.

The National Party, having won the 1948 general election (in which the of black African majority was prohibited from participating), began implementing its grand scheme of racial segregation known as apartheid.

In April 1950, Parliament passed the Group Areas Act, a notorious piece of legislation that sought to push black Africans and other non-white races further away from the cities into racially segregated townships and suburbs. Settlements like Olifantsfontein, where Skhosana was born, were targeted for total destruction by the authorities.

In 1964, Skhosana and his family found themselves back in Endulwini, not far from where their forebears had lived for generations as farmers, but now dumped in a soulless zinc shack with a bare floor.

From being owners of a little bit of land in Olifantsfontein, they were now, again, merely tenants on government land. “We left everything [behind]. Our chickens, cattle, everything,” he says about their removal.

The removals were harsh, inhumane, heartless and barbaric. Residents would be surprised by bulldozers tearing down their homes while government trucks, escorted by armed police, roared outside, waiting to be loaded with whatever items they could salvage.

They were given no time to gather their belongings. The state machinery wanted them off the land. Some families like Skhosana’s managed to salvage the zinc sheets they had used as a roof. These later came in handy at their new location, where they used them to extend the little shack allocated to them.

Rude and impatient government authorities then took down the names of all who lived at the new address and allocated each family a metal bucket to be used as a toilet. And so began life in the new settlement that grew into what is Tembisa.

“This was a bush here, all around here there were lots of trees. If it was not for the forced removals, we would still be living here on my grandfather’s farm. I was still young when the removals happened. But it wasn’t right. It was bad,” says Skhosana.

The South African History Archive notes that Tembisa was established in 1957 on a farm originally owned by Mr JHM Meyer and Mrs MWZ van Wyk and that the land was purchased at R3.52 a hectare with funding from the National Housing Commission and government loans.

It became a new home to victims of forced removals from areas east of Johannesburg. These included the settlements and townships of Olifantsfontein, Sterkfontein, Verwoerdburg, Irene, Six Mile, Edenvale, Witfontein, Kempton Park, Modderfontein, Mooifontein and Alexandra.

It grew from a township of a few hundred houses to a population of more than 460 000 in the 2011 census.

In 1996 Skhosana lodged a claim under the 1994 Restitution of Land Rights Act for the land his parents were forcibly removed from in Olifantsfontein. The claim was settled in 2009 and he was paid R60 000. He is also planning to lodge a claim for this land in Tembisa.

In Olifantsfontein on a weekday afternoon, Skhosana, Godfrey Thobejane and Norman Bhuda walk carefully among graves located on a thicket behind a printing factory. The three are members of the Tembisa Land Claims Forum, which helped claimants to understand the process and prepared them for the application process with the Commission on Restitution of Land Rights.

[Poor compensation: Godfrey Thobejane’s family land is now an industrial area that is still called Olifantsfontein. They settled for cash (Oupa Nkosi)]

Thobejane, who lives in Masemong section, was born in Olifantsfontein in 1957. The following year his family was forcibly removed to Tembisa. In 1996 his family lodged a claim which was successfully settled in 2007.

The land from which they were removed is now part of the thriving industrial area known by the area’s old name, Olifantsfontein. After more than 40 years of living and establishing their roots in Tembisa, none of the family was interested in going back to the land of their ancestors. They settled for the once-off R60 000 cash settlement instead.

The money was shared equally between Thobejane, his three brothers and four sisters. In the end each one’s share was just R7 500 — for the loss of their ancestral land, the break-up of their homestead, the pain, suffering and emotional trauma caused by their forced relocation.

Thobejane, a bearded, silver-haired, jolly man with a sense of humour, shakes his head furiously when asked why the family did not opt for the land instead of the measly cash payout.

Although his family’s roots are in Olifantsfontein and he was born there, home to him remains Tembisa. He was born in 1957, the same year the apartheid government established the township.

It was in the streets of the township that he was schooled and politicised during the 1976 student uprising, during which he confesses he was part of a group of students that set alight state offices.

“I came here when I was a toddler. I don’t remember anything from Olifantsfontein,” says Thobejane.

In Moyeni section, Hendrik Jiyane is preparing to reclaim the land once owned by his grandfather, whose name was also Hendrik. He was ignorant about the process of lodging a claim and missed the December 31 1998 deadline.

In June 2014 President Jacob Zuma signed an amendment of the Restitution of Land Rights Act, paving the way for people to submit new claims from July of that year. However, in July last year, the Constitutional Court ruled that the amendment was invalid, on the grounds that Parliament failed to allow for proper consultation before passing the law.

Arduous: Norman Bhuda, along with Godfrey Thobejane and Hendrik Jiyane, helps people with the restitution of land rights process (Oupa Nkosi)]

The court further ruled that no new claims could be processed until those submitted before the 1998 deadline were finalised. This means people like Jiyane face another long wait. Skhosana’s second claim — for his grandfather’s farm — must also wait.

Jiyane’s grandfather owned a large portion of land in what is now part of Jiyane section. The land is now a residential area comprising old-style township matchbox houses, stylish revamped houses, bonded houses, shops, schools and taverns.

According to the StatsSA’s 2011 census, the section had a population of 2 958 people living in an area of 0.24m2.

Jiyane, who was born in 1950, doesn’t know the exact size of the land his grandfather owned. But even though he was just a little boy, his memories of life on the farm are nothing but sweet.

“Eh, eh, eh, eh!” he shakes his head and smiles when asked what life was like on the land.

“We had large fields. We farmed veggies. We had dams on the farm. We would open the taps and water the veggies. We had how many? One, two, three fields. My grandfather was a farmer. We planted cabbage, onions, tomatoes, beetroot, everything,” says Jiyane.

His grandfather was a wealthy man. He sold his vegetables in the settlements around this eastern part of Johannesburg. Through the years he had managed to buy himself a truck for his farming business and a stylish private car, a Studebaker. He lived on the land with his four wives, his brothers, sisters, his children and grandchildren.

[Memories: Hendrik Jiyane’s grandfather owned a large piece of land in Tembisa’s Jiyane section, but he remembers the fields of vegetables (Oupa Nkosi)]

But the prosperous Jiyane farm, together with its vibrant communal family spirit, did not escape the long, brutal arm of the apartheid authorities. In the mid-1960s, the extended family was systematically uprooted from their land.

The family was broken up and sent off to live in the standard four-roomed matchbox houses in different parts of the township.

Jiyane still lives in the one his family was moved to in Moyeni section. His grandfather was the last to leave in the mid-1970s. He was moved to Makhulong section. He did not live long after being moved.

Jiyane hopes that when the process to lodge land claims is reopened he will at least get an opportunity to find some sort of compensation for the family. Returning to the land, which is just less than 2km from his house, is out of the question though.

Besides the land now being an occupied residential area, he reckons starting over would not be easy.

“There is no one [among the older generation] who doesn’t want to return to the land [from where they were forcibly removed]. But, if you say that to our children, they will ask you, what are we going to do there?” laments Jiyane.

Claiming the land and getting compensation will not be an easy road to travel. Last year the Land Claims Commission revealed before Parliament that 166 000 new claims were lodged since the reopening of the process in 2014 until the court ruling last year. The commission revealed that there was still a backlog of 7 419 land claims outstanding from the 1998 period.

Thobejane says the Tembisa Land Claims Forum had received about 5 000 land claim applications between 2014 and 2016 from Tembisa residents. These were people who were either not aware of the initial process, or those who had been ignorant about how they and their families had ended up in Tembisa.

Thobejane says the settlement of the claims lodged before the 1998 deadline led to a sudden rush of claims.

“Three times a week we transported people to Pretoria in a 22-seater bus. We even had to ask the commission to come to the people,” says Thobejane.

A mobile caravan was dispatched to Tembisa for a week in 2015 to process land claim applications.

In Olifantsfontein, the forgotten graveyard provides a glimpse into the people who once called this place home. One of the many granite headstones — hidden among aloes, dense trees, grass and heaps of rubbish — reads: In memory of Maria Sebeela. Born 26-10-1873 at Adamshoop. Died 1-4-1942.

Another reads: In loving memory of Mogodi Stephen Morake. *1862 + 1952/08/03.

[Neglect: The gravestones of some black people remain in the veld, unlike those of white people, which are fenced off and protected (Oupa Nkosi)]

The graveyard is now bordered by an illegal dumping site. The repugnant stench of human excrement and rotting animal carcasses saturates the air.

This is worlds apart from the state of the graves of three white people in Jiyane section. The graves, at a street corner, are fenced off and the area around them is paved with cement.One has an imposing headstone and reads: Hier rus Jon Georg Duvenage. Gebore op die 7 Mei 1821. Oorlede op die 20ste Junie 1887 …

“I feel pain because the graves of my ancestors have been flattened. But there in Jiyane there is a grave of a white man which has been well preserved by our own government,” fumes Skhosana.

[Days gone by: Somewhere on the land that is now occupied by Endulwini Primary School were the graves of people who lived there before their families were forcibly removed under apartheid. (Oupa Nkosi)]

In the centre of Olifantsfontein, heavy trucks and big machines roar in the late afternoon. Scores of workers in blue overalls walk about the streets and the factories. Nothing suggests this was once home to a vibrant community of farmers.

Skhosana says: “This place has changed so much. Even the old people would be frightened if they were to be resurrected. They would be totally surprised.” — Mukurukuru Media