Hadebe’s efforts “to be as open as possible” and outline Eskom’s financial difficulties frankly set a very different tone from past engagements

There is a story I was told about Eskom’s new interim chief executive Phakamani Hadebe and his time at the treasury.

He was part of the team who, in the early days of democracy, worked to get South Africa’s credit rating raised to investment grade.

He is said to have sat in meetings with ratings agencies, doing calculations based on their own formulas and arguing fiercely when he disagreed with their assessment of the country’s performance.

This depiction of him — a civil servant battling to establish the investment credibility of his country in the eyes of the international community — had a particular resonance when he presented Eskom interim results this week.

“I don’t see my responsibility as being that of Eskom but I see it as that of the South African economy, our country,” he told journalists. “And I’m honoured that I have had people who have felt that I could add value in this space, and I’ll do my best to do so.”

Hadebe, who before a stint in investment banking spent 19 years in government, first at the treasury and then successfully rescuing another state-owned entity, the Land Bank, was quick to call the story “the height of exaggeration”. He emphasised that it was a team of people who achieved the investment rating.

“It’s because we had a common strategy in South Africa, where everyone was following the same goal, on spending, on savings but, over and above that, on guarantees and on borrowings.”

But in recent years, a common strategy by government has arguably been lacking as political battles over patronage had infected the workings of parastatals such as Eskom.

In its case, it has resulted in a qualified audit corruption allegations that refuse to go away, and Eskom’s credit lines being frozen. This in turn precipitated a liquidity crisis that has almost brought South Africa’s economy to the brink.

Much like his role at the Land Bank, Hadebe said he had been called in “to stop the bleeding”. And he is confident it can be done.

Since the announcement of the appointment of Hadebe and the new board under Jabu Mabuza, Eskom has secured, “in principle”, the R20-billion the company needs by March, enabling it to publish its much delayed interim financials before the January 31 deadline and narrowly avoiding the trading of its bonds being suspended by the JSE.

Hadebe said the first R10-billion would be in Eskom’s bank accounts by February 1 and the next R10-billion was expected on February 27.

They have also begun the task of dealing with corruption in the ranks of Eskom.

The “permanent suspension” on Wednesday of former interim chief executive officer and chief information officer Sean Maritz is the latest development.

He is alleged to have signed a letter advising consultancy firm McKinsey that more than R1-billion in payments to the firm were lawful, despite an internal inquiry finding otherwise.

Meanwhile Matshela Koko, the head of generation at the power utility, has again been suspended — reportedly on new charges including misleading Parliament.

But besides addressing corporate governance concerns and Eskom’s immediate liquidity crunch, its capital structure had to be reviewed, Hadebe said. Eskom’s reliance on debt had left its gearing rate at an unsustainable 72%.

“Over the next two and a half months, we will have to ensure that we review the sustainability of Eskom,” he said.

This is expected to include the conversion of debt into equity, and discussions with government institutions such as the Industrial Development Corporation, the Development Bank of South African and the Public Investment Corporation to find ways to go about this.

Hadebe’s efforts “to be as open as possible” and outline Eskom’s financial difficulties frankly set a very different tone from past engagements, according to an analyst. There was “a sense of sincerity”, “a humbleness” and an acknowledgement that there was work to do to win investor trust back.

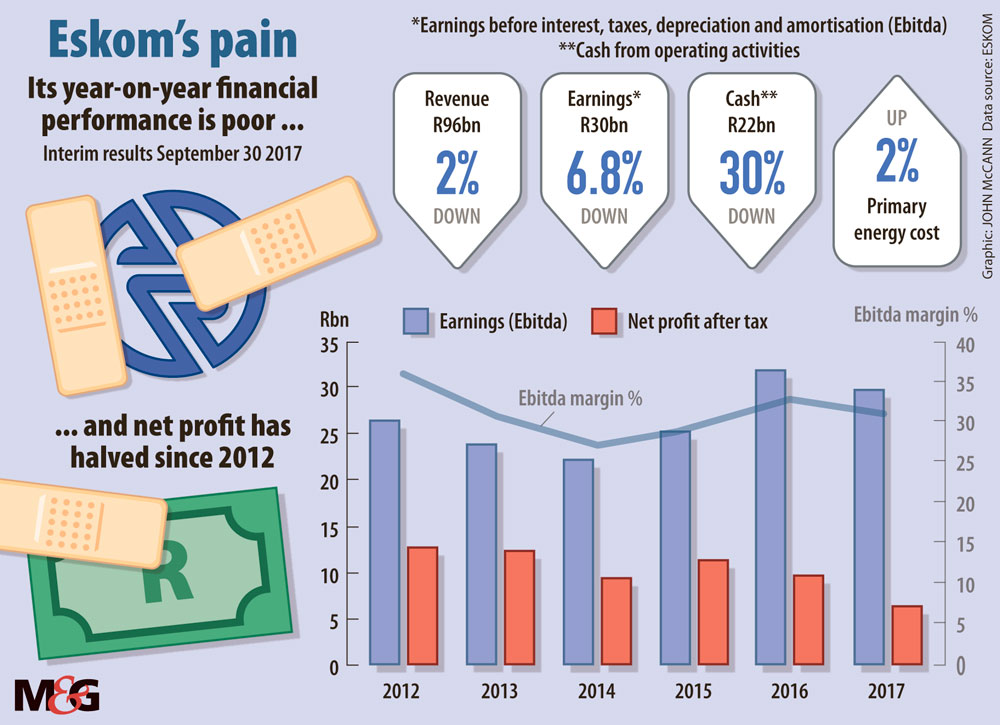

But there is no illusion about difficulty of the task ahead. Eskom’s finances are dire. Its profits for the period to September 2017 were down 34% to R6-billion. This has not been helped by a tariff decision by the National Energy Regulator of South Africa to allow it a price increase of only 5.2% .

The company’s debt has risen 10% to R367-billion and its cash from operations has shrunk by 30%. Outstanding debts, predominantly by municipalities, have risen from R16-billion in 2016 to nearly R20-billion.

(John McCann/M&G)

Eskom’s acting chief financial officer, Calib Cassim, warned, given the cyclical nature of Eskom’s business, it would be very hard for the company to break even by its financial year-end.

Although its auditors gave Eskom’s interims an unqualified report, it raised concerns about liquidity and corporate governance.

The company’s weak balance sheet means it cannot commit any money to a nuclear programme, Eskom revealed.

It has been pointed out that the nature of the clean-up at Eskom will require significant “political cover” to ensure that both the board and Hadebe can get the job done.

In the case of the Land Bank, it had been bedevilled by corruption, with money dished out to officials and their friends and ballooning bad debts.

In 2008, the bank was transferred from the then ministry of agriculture and land affairs to the treasury, and Hadebe had the political backing to right the ship.

Eskom is a much bigger and more difficult beast and political pressure has resulted in the departure of many executives in recent years.

Although it is now being overseen by a team of ministers, including Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, it ultimately reports to Public Enterprises Minister Lynne Brown.

Mabuza has said there was a clear delineation of roles between the board and Brown from the start.

For her part, Brown said: “The country has the highest expectation in the new board to reposition Eskom, tighten its governance systems and traverse a changing energy environment, while placing Eskom on a sound financial footing. The board has the full support of government.”

But investors and industry players are sceptical and doubt her ability to support the new leadership as it uproots vested interests within the organisation.

But Hadebe believes his time in government has prepared him for the politics that comes with this job.

“I know the dynamics, I know how [government] operates, I know the responsibilities of the line ministers. If there are any areas where I am uncomfortable, I know how to manage that.”

His appointment at Eskom ends in three months but he refused to say whether he would stay for longer than that, or under what conditions he would consider doing so.

Much will depend on the full-year results Eskom puts out mid-year and whether it manages to shake off the qualified audit opinion.

In the political life of South Africa, a lot can happen in three months.