A new chapter: Wade Smit's fascination with isiZulu stories and his desire to see more of them made available to a wider audience led him to start a publishing house with his wife

In July 2017, husband-and-wife team Ariana (née Munsamy) and Wade Smit started a publishing house called Kwasukela Books, because of a desire to see more contemporary isiZulu works outside of the social media realm, where there is a great deal but largely in a serialised form.

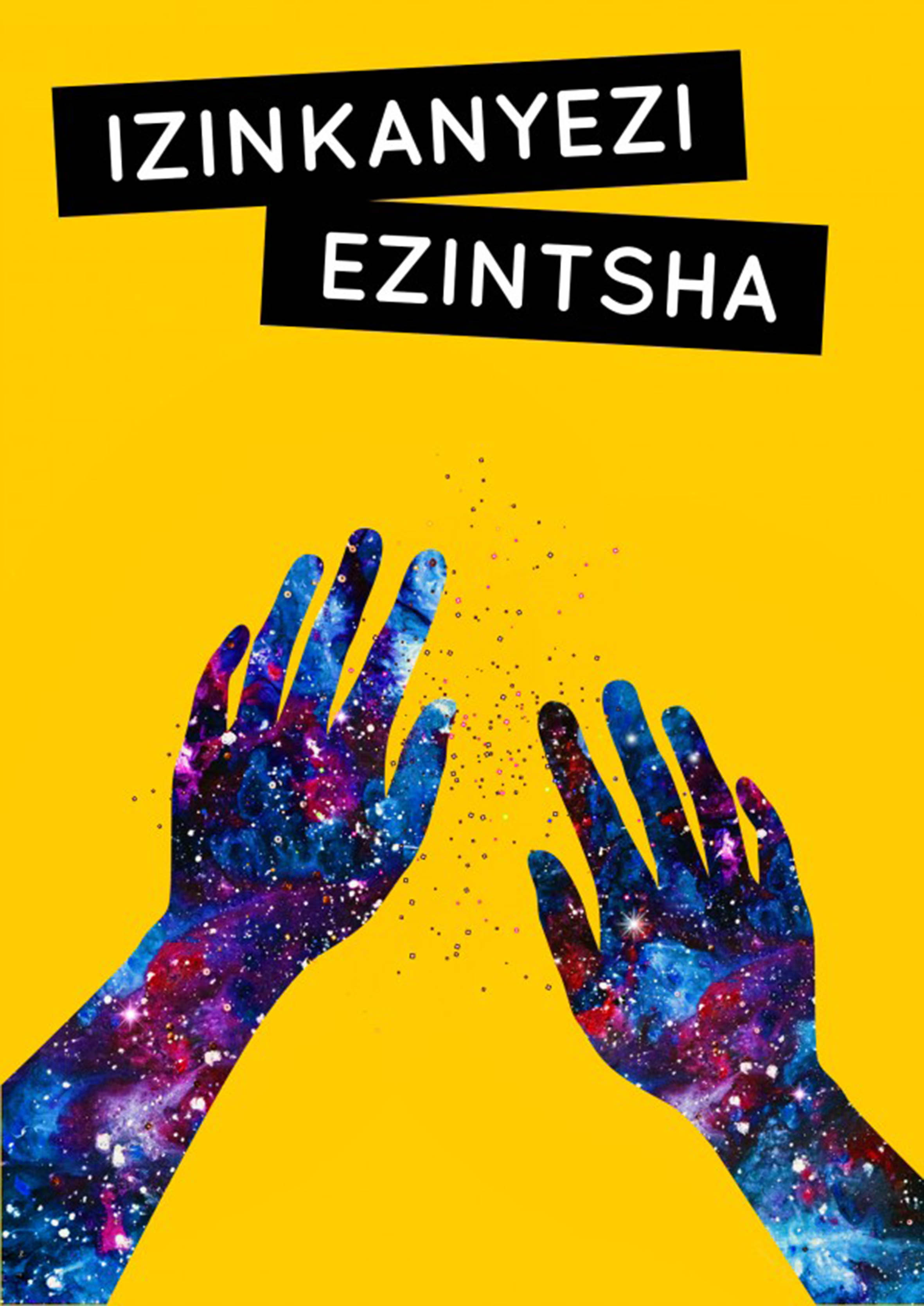

The couple, both of them writers, solicited participants for an anthology of speculative short stories in isiZulu called Izinkanyezi Ezintsha. After selecting the anonymous submissions, a small print run of the book was published, with more volumes to follow later in the year.

[Izinkanyezi Ezintsha is the debut Anthology under Wade and Ariana Smit’s publishing house Kwasukela Books]

Wade, also a freelance editor with uHlanga Press, spoke about his connection to isiZulu and the future of the company.

The most passionate literature scene is in indigenous languages but most people don’t know this because writers and readers are not following traditional publishing.

For a lot of the writers, because the indigenous market is nonexistent, their only avenues are free platforms. Social media has become this really accessible easy platform for people to workshop their writing, give feedback. It’s actually really big if you go into it and look for the groups on Facebook. It’s more Facebook than Twitter.

What format does it take?

It’s mostly through a serial format, like it could be novels or short stories, but you find that the novels are the most popular. So you get chapter by chapter — very short chapters — going on for a long time, like 60 chapters or 80 chapters.

How much does apartheid have to do with this?

More so than apartheid, it’s the legacy of colonialism. When you look at the history of the African continent in terms of literacy, there was already a deep literary history. Colonialism destroyed a lot of those writing systems, to the point where they just don’t exist anymore.

Essentially, in all countries of the African continent, with the exception of maybe Ethiopia, you have to start again, and now you have to adopt the Western way of writing in Latin script.

You had to redo the orthography for every word and that is all done by the coloniser.

Apartheid made it worse because information and art became so politicised.

How did you get involved in Zulu language literature? Do you also write in isiZulu?

I took isiZulu in grade 10 instead of Afrikaans. In primary school, we did both. I loved the short stories they prescribed. After high school, I got heavy into reading isiZulu newspapers because they were the most accessible isiZulu literature available.

Beyond that, I discovered that I could order some old school novels and poetry books from Shuter & Shooter, a mostly educational publisher that provides prescribed text books. My wife bought me a huge collection of assorted books for my birthday and it was just the best thing ever.

What made you choose isiZulu over Afrikaans?

My home situation influenced my decision. I come from a white household with divorced parents. My dad is not in the picture. My mom is a single mom working from six in the morning to six at night running her own company, so I never see her.

The only person I see as a mother figure is my domestic worker, Thembi. To me, she was like my mom. Since basically birth, this was the person I saw. She took me everywhere and taught me things. She spoke to me in isiZulu but then, when I grew up, I grew up in a very Eurocentric cultural space, so it gets taught out of you.

At the end of 2009, my Afrikaans uncle, who I was not on very good terms with, suggested “Why don’t you change from Afrikaans into isiZulu because it will help you in the workplace. It will help you get a job. You know, the country is changing.”

There was an element of truth to the suggestion but then it was also, like, “You have just reminded me of how much I like this language.” So I took it as a second language in grade 10.

When you left school what did you study?

I didn’t know if I wanted to study. It’s a divorced household. My father was always telling me, “Don’t study, it’s a waste of time, just join the family company. You don’t need any of this. It’s expensive, the economy…” and all this. I was like, “okay, I guess he is making a little bit of sense”.

My mom was, like, “You absolutely must study, you need an education.”

My now wife was, like, “You know you have to study. You can’t join your family’s business. You will end up as just another washed-up white guy drowning in your privilege.”

There was something about that, even in my ignorance, that I did not want.

At first, I wanted to do filmmaking because it was something that I thought would be fun to do with my girlfriend. But in the registration queue I saw a sign for English, archeology and anthropology. I found the course descriptions a bit interesting and, on a spontaneous decision, I just chose English, anthropology and archeology.

How did that lead to you forming a publishing house?

It was basically from English, because it was in that department where I had some incredible lecturers. Dr Christopher Ouma, Dr Khwezi Mkhize, one of my tutors Thembelani Mbatha, another lecturer Victoria Buthelezi, and a lot of others.

They were very receptive to the language idea and questioning literature in different languages.

At the time I was reading more and more isiZulu texts and I started to find a lot of correlations to what I was learning in my own time and what they were teaching. When my wife got me those books, some were historical texts by [Rolfes] Dhlomo.

It was interesting because I was learning historical stuff at university and then to see this completely different historiography or point of view and different way of writing history in his books, I just applied that to my English essays and my lecturers were very receptive to it.

It just kind of built up and I felt like we needed to do something about it because we are still in a very Eurocentric cultural space. I just wanted to read more isiZulu that was more current and more relevant.

Was it easy to solicit and find the right writers?

It was hard. We had no established audience, nobody knew about us. We were just bursting on to the scene, with no reputation whatsoever to our personal names, becoming a company name.

I was hedging my bets on the Facebook groups that we were looking at or reading stories on. So I was, like, if I can get the attention of these writers then we can actually get them published. So we just did heavy social media marketing. We got a decent amount of submissions but nowhere near the amount that we thought that we would get. Maybe about half.

By the end of the submissions period, there were more than enough stories to make a full book. We could have made a book with a whole lot more stories but not all of them fit the brief of speculative fiction.

How much was your first print run?

We printed only 100 copies because we were running on a very small budget. We figured this could be a test run to gauge our popularity, response, and it’s a safe number. Because printing companies these days are pretty equipped to do smaller print runs, we can print as soon as we need the next batch, like one or two months in advance.

You said publishing, distribution and advertising for the Zulu language has to be rethought. What did you mean by that?

If you are thinking about advertising and distribution, for instance, where are you going to advertise? Who is going to distribute? A small publishing house will never have the resources and the momentum to say, let’s make a big marketing campaign, let’s go directly to the distributors.

With us, there is no in, because the bookselling industry so far has been very Eurocentric, focused on English and Afrikaans. So you have to make up your own method and find ways of marketing for free, by depending on word of mouth. So we have turned to independent booksellers because they are much more responsive. You don’t have to go through a big distributor first.

Design wise, different design appeals to different people. Different cultural aesthetics have different resonances. If we were to publish this book that we have just published with a cover that looks, first of all, like an educational book, you can easily dismiss it as another textbook or high school book.

If it looks too much like an Exclusive Books bestseller, that format is very eye-catching but it doesn’t tell you “this is new, this is different”. If it had to shout, “this is different, this is new”, people would be confused because they would be able to recognise that this is a book but, if I open it, I can’t read it.

So we have to prove that there is a different type of book that can exist and it is not in English, it is not in Afrikaans, it’s an isiZulu book and has its own way of doing things.

I didn’t think that this would be necessary until I spoke to people and realised that there is a lot to prove. So rethinking aesthetics was a big thing for us.

From what you have learnt about the industry, which isiZulu writer would you say is the most highly regarded or sells more than most?

I think probably the closest to what you are describing is Mazisi Kunene with uNodumehlezi ka Menzi. That book to me is probably the single most impressive published piece of isiZulu literature.

I would say he is the star, which says a lot because he is coming from a very different era and he is more like a legend than a star.

The way isiZulu literature is set up, I would say a star to me is Mzi Mngadi because he wrote a lot of set books and I enjoyed his set works, like Ababulali beNyathi and Kuyoqhuma Nhlamvana. Those books to me were everything. But he is not quite a star because those books were read almost exclusively by matric students.

In which stores can one find Izinka-nyezi Ezintsha?

It is currently at Bridge Books in Johannesburg, Clarke’s Books in Cape Town and MyAfricanBuy online. We are working on other independent bookstores as well as Exclusive Books. It retails for R150.

For more information visit kwasukelabooks.com