ANC national chairperson Gwede Mantashe.

At the ANC’s Luthuli House headquarters, he had the unenviable task of trying to speak with a single voice for a fractious organisation. Gwede Mantashe’s position as the party’s secretary general at times proved to be so impossible that he found himself flip-flopping between positions, an act that has been termed “mantashing” — a sudden and unexpected change in thought or logic.

Will he need to mantash in his new job as the minister of mineral resources, overseeing what can be a fractious industry? Or, will his 30 years of experience as a miner and unionist mean he has the leadership skills to get agreement?

Mantashe has kick-started new negotiations over a third Mining Charter. His predecessor, Mosebenzi Zwane, had caused a major rift between the industry and the government when he published a new Mining Charter in June last year. The result was that mining shares lost more than R50-billion in value over the next few weeks and the Chamber of Mines described the document as illegal and applied to the high court to have it declared unconstitutional.

Present at last weekend’s mineral resources meeting was the Chamber of Mines, which represents 90% of the mining companies, organised labour in the form of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), Solidarity, the United Association of South Africa and the South African Mining Development Association, and members of the parliamentary portfolio committee on mineral resources. (See “Zwane’s mining DG in firing line”, Page 15.)

“The first problem has been resolved, [that] of not talking,” Mantashe said at a press briefing on Tuesday. A few months ago, the parties were not willing to speak to one another but now the department was committed to finalising the charter by end of May, he said.

The key issues to be addressed include empowerment targets, the issue of “once empowered, always empowered” and a contentious 1% levy on mining revenues.

Known to be a rigorous negotiator and a lover of debate, Mantashe described the discussions as robust and open. Those present interviewed by the Mail & Guardian said a long and heated debate preceded the agreement to use “charter three” as a basis for new discussions. The chamber had expected the department to start the process from scratch.

“The starting point for an engagement is not to say there is nothing. It is to say: ‘You have problems with Charter 3; what are those problems?’ That’s where you start. Let’s identify the problems,” Mantashe said.

“The chamber gave us their problems with charter three in writing.The teams that are working on the details will have something to work on,” he said.

Two task teams have been established to identify the issues that will be discussed. One will focus on transformation and the other will focus on growth and competitiveness. The teams are expected to report back within three weeks.

Previously, the chamber raised issues about the new ownership empowerment target, which required mines to increase their black ownership from 26% to 30% within 12 months. Mining companies would then be compelled to maintain the 30% ownership level, essentially discarding the “once empowered, always empowered” principle.

Surprisingly, Mantashe said this was not an issue at the weekend’s meeting. “There’s no problem around the 30%, that’s it. Whether we’ll revise that issue is ongoing”.

Mantashe said there were arguments that 30% ownership was not substantial. “If you move to 30% from zero, that is substantial movement. My argument is 30%; if we agree with it, let’s meet it and comply with that.

If we grow it then it will be an issue that’s happening systematically”.

But the senior executive of public affairs and transformation at the chamber, Tebello Chabana, said saying the 30% ownership target was not an issue was “not correct” because it was still “very much unsettled”.

“We made it clear that the issue of an ownership target is intimately linked to the resolution of the case that we have related to recognition of past transactions [once empowered, always empowered]. That’s a critical part of declaring what recognition you’re getting for the empowerment that you have already done and how does that relate to any new target.”

The chamber did not want to give a blow-by-blow account of the matters discussed at the meeting. The negotiations had just started and there was no certainty about how an issue could end up, Chabana said.

David Sipunzi, the secretary general of the NUM, said their only issue was how the 30% would be constituted. “It should equally go to workers, community and entrepreneurs. Ten, 10, 10.”

The contested charter three states that 8% of the mining right should go to employees, 8% to mine communities and 14% to black entrepreneurs.

In addition to ownership targets, the third charter also required mines to pay 1% of their annual turnover to the 30% black economic empowerment partner before any distributions, such as dividends to shareholders.

Charter three asks mining right holders to employ “a minimum threshold of black persons which is reflective of the demographics of the country”. Fifty percent of the board members and executive managers should be black people. At junior management level, 88% of all appointments must be black people, of which 44% must be black women.

Solidarity’s Gideon du Plessis said everyone at the meeting had agreed that the charter was badly worded and riddled with ambiguities.

“We agreed that the definition of HDSA [historically disadvantaged South Africans] that included the naturalisation clause, which included the Guptas, would be scrapped.”

He added that, although not finalised, there was a “discomfort” among those present that the exclusion of white employees from the employee share ownership programme would create division among lower-level employees in the mines.

The chamber also took issue with the establishment of the Mining Transformation and Development Agency, which is to manage the shareholding of mining communities. Foreign suppliers are expected to pay a minimum of 1% of their annual turnover generated from local mining companies to the agency.

At Tuesday’s briefing, mining community members criticised Mantashe for excluding them from the weekend meeting. In February, the high court in Pretoria ruled that communities affected by mining must be included in talks to formulate a new charter.

Mantashe said the department had a planned programme of consultation with mining community members, not only with those who went to court. The department said it would conduct discussions in major mining provinces and major labour-sending areas.

Those who attended the meeting said there was a general consensus that the charter and the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Amendment Bill had to be finalised to restore investor confidence.

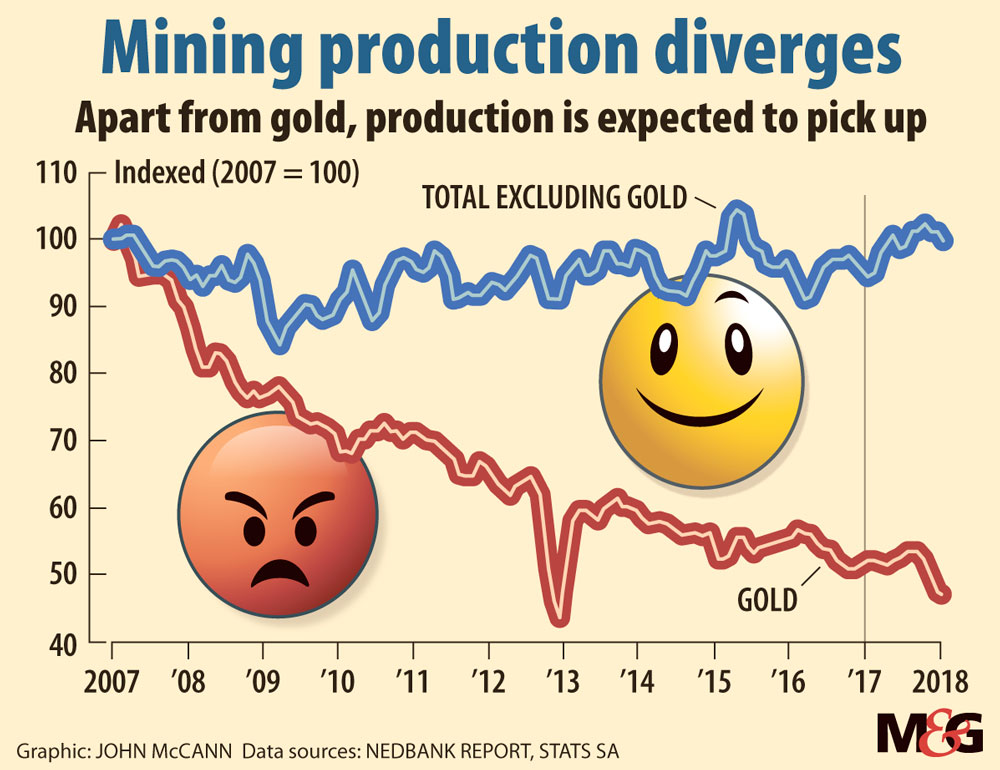

Mining production grew by 2.4% in 2017 but Chabana said the country could be doing better. A survey by the chamber revealed that there was a huge financial upside for South Africa if the country’s mining industry moved back towards “best practice” in terms of regulation and policy.

Chabana said the 16 companies that participated in the survey had already planned to invest about R164-billion but they said they would be willing to spend an additional 84% (R122-billion) if South Africa got its regulatory house in order. “That’s just from our members. Imagine those others that are holding back and not investing, or those that have actively turned away from investing in the country.”

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust trainee financial reporter at the Mail & Guardian