Kiri’s first criminal act involved a stolen Coke

I work with words. Words allow me to give voice and character to the world around me. But words are shysters. They change and grow or shrink themselves with context or emotion. Sometimes they tell the whole story, other times they disguise and obfuscate. But their importance is undeniable.

One word I find myself thinking about constantly is “faith”. Faith, if I were to describe it to a small child, would be like the wind. You cannot see it but you can see what it moves. It is an invisible, unthinking, unchanging force. It cannot be quantified.

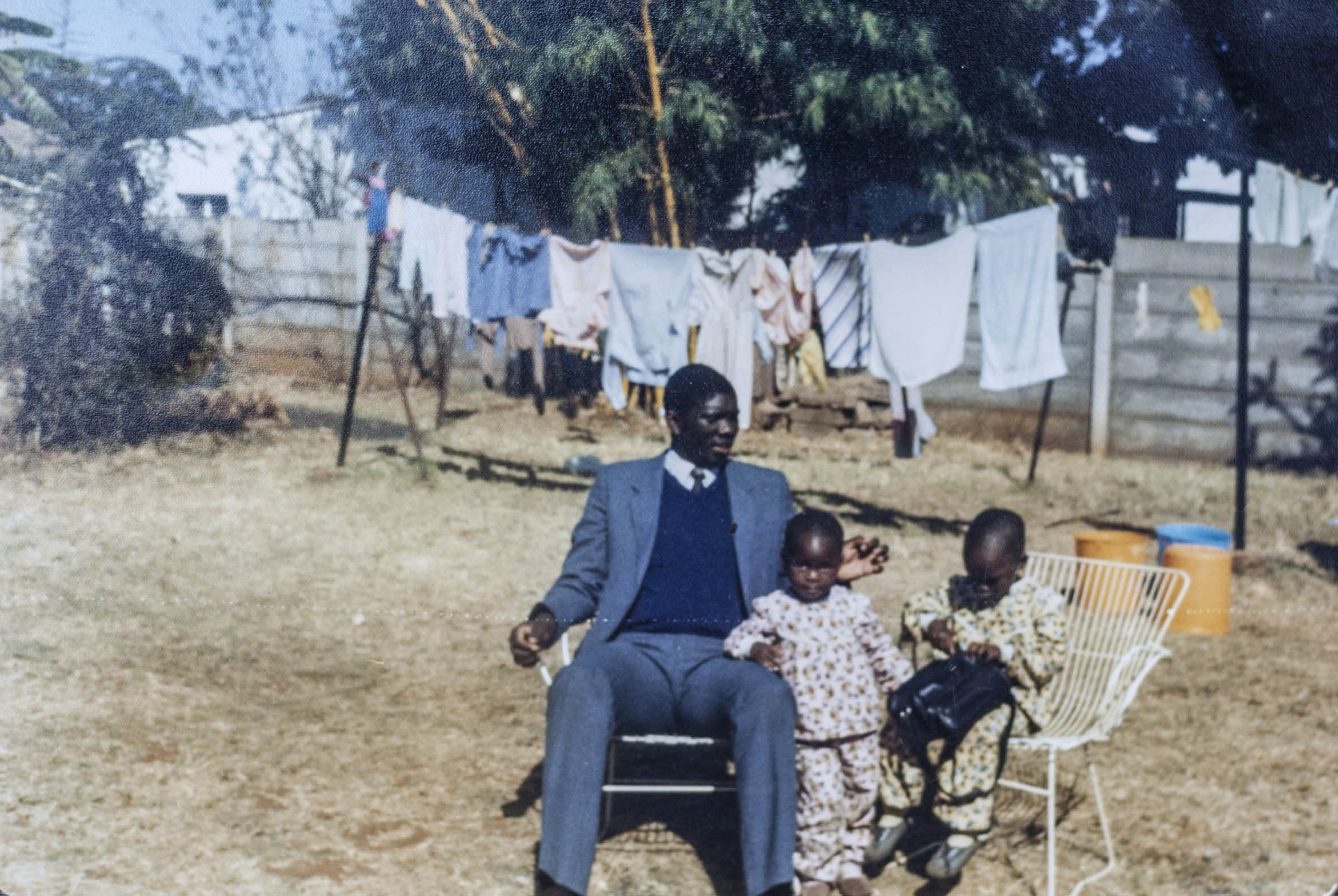

[Kiri, her sister, Beth, and father, Martin]

I was eight when I was baptised at Our Lady of the Wayside Church in Mount Pleasant, Harare. Uncle Manu and Mai Chiedza were designated as my godparents. My mother, bless her soul, had made the mistake of finding a lily-white abomination with matching stockings for this important event. I was given strict instructions that this ensemble would remain clean until after I had taken a swim fully clothed. At least in my understanding.

To my disappointment, however, after the priest had explained what the baptism meant and how I was born with the stain of original sin, he simply wet my forehead.

I was “cleansed” and that was that.

My soul was cleansed, guys. This was huge.

I would finally be able to consume the body and blood of Christ in a process called transubstantiation. The Roman Catholic Church holds that the same change of the substance of the bread and of the wine at the Last Supper continues to occur at the consecration of the Eucharist, when the words are spoken in persona Christi: “This is my body … this is my blood.”

In other words, we are led to believe that the Eucharistic offering is literally and miraculously changed into the actual body and blood of Christ. The manner in which the bread and wine transform is one of the mysteries of faith.

To be closer to God, you must believe what we have told you.

Bound by faith

My godmother had the kind of skin that announced her secrets. It blossomed with bruises, yellowing black eyes and crimson split lips. We didn’t need a town crier to know this was a woman under siege.

Prayer was her solace and succour but there’s only so much fervent benediction can do. Those around her seemingly did not see what was happening — or decided the most Christian thing to do was to mind their own business because God forbid she should divorce him. Death before divorce was a more palatable option.

For black people, especially for the older generations, church is not just a place of worship but a community. A second home, a place to find the one “tribe” that matters where the bonds of anger and pain fall away. I’ve watched prayers being uttered so wholeheartedly. Like incantations. The rosary beads squeezed with whitened knuckles.

The way black folks love them Jesus makes sense to me. There’s another life to come, a life to look forward to where blackness is neither a hindrance nor a source of shame. Life on this earth is fleeting. Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord for he will have eternal life. But you have to work for that eternity of paradise.

[Martin and Prisca renewed their vows at the Sacred Heart Cathedral in Tshwane. Their daughters, Kiri and Bethel, started their service to the Church when they became altar-servers at St Joseph’s Church in Bradford, England]

Earthly life is unfair. It is a series of disappointments and hurts that are designed to test you and prepare you to sit at the table of the Lord.

What was important then and still is today is keeping up appearances and acting out the ritual of the mass rather than keeping the faith. The chancel lamp must remain aflame. The right hand placed over the left to receive the Eucharist. The genuflection like a choreographed dance. The responses recited rather than heard and felt. The ritual, however hollow and vague, repeated.

Keeping the faith

Now that I’m older, and have pulled over on the roadside of the Stations of the Cross, and stopped reciting the mysteries of faith, I must be honest and say I can’t reconcile Christianity with goodness, truth, love and honour. I can’t, with an open heart and functioning mind, keep calling myself a member of the Christian faith. At least not with the bastardised version of Christianity that I saw as a child or see now.

[Kiri and her sister Beth in their school uniform]

The Christianity preached by a Palestinian freedom fighter whose fate was sealed by Pontius Pilate’s handwashing isn’t the Christianity I see today. The Church didn’t save me. Rather, it opened my eyes to contradiction, exclusivity and hate.

As with most cons, the more I see, the less I understand. Why are women held in low esteem? Why are poor people rejected and dehumanised within a religion founded on the very tenets of inclusion and community? Why are refugees dying in watery graves because so-called Christian countries would rather build walls than fellowship? Why is one woman’s life a worthy sacrifice but saving her from a nightmarish existence tantamount to grave sin?

Father Peter Daly, of the Archdiocese of Washington, DC, explains best with a story: cars registered to the Vatican display licence plates with the letters SCV. Officially, those initials stand for Stato della Citta del Vaticano (Vatican City State). But ironic Italians say SCV stands for Se Cristo vedesse (If Christ could see it).

What if Christ could see it? Would he recognise the Church?

Spirituality unbound by institution is a more viable option at this stage in my life. Like keeping God but throwing out organised religion. For older congregants, my friends and I, who nevertheless consider ourselves just as spiritual as they are, represent an exodus from organised religion into the throes of secularism.

But that’s not the full story. When you consider the issues facing young people today, the reasons for the exodus unfold. In rejecting organised religion and its contradictory rules and sanctions, younger generations are expressing a progressive faith in and passion for social justice.

The church exhorts us to have faith in things that betray the truth we see with our own eyes. Its unforgiving and colonised constancy tries to bind us in beliefs and strictures that cannot survive the reality before it. Our parents may scoff at the idea but there’s no denying that it has been on the precipice for decades.

For the younger members of the black community, on the continent and in the diaspora, there has been an awakening to a spirituality that leaves no one behind. And, as one among them, I am committed to the idea that I don’t need religion to tell me how to be a decent person.