From Seedtime

Omar Badsha may never get the same recognition that many of our struggle and documentary photographers have. He has always been too much of an outsider, too much of an activist.

“I’m not your photographer’s photographer,” he says. “I’m not made for that. I’m not precious about who I am. I’m not producing work for my ego. I produce work because I must.”

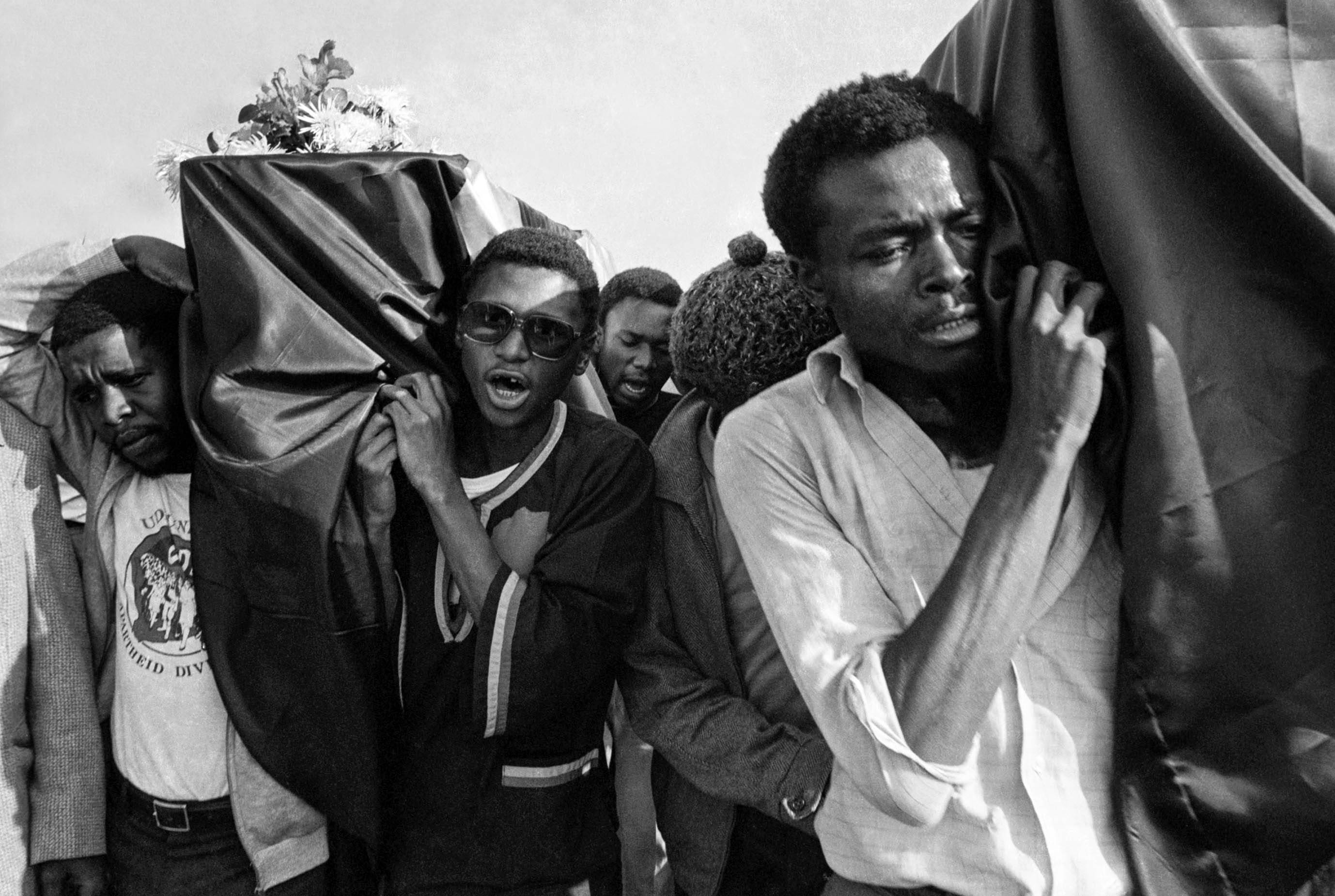

Seedtime, Badsha’s retrospective collection of photography, will surely change that. It’s named after a line in a Mafika Gwala poem that was written in response to the 1976 Soweto uprising — at a time when children had reignited the anti-apartheid struggle.

Badsha says: “It’s a statement about post-apartheid South Africa and that [1976] vision, and how it gets lost. If it’s not addressed, there will be another Soweto.”

He hopes the book and an accompanying exhibition will open space for more dialogue. “We fought for the marginalised, the downtrodden, the poor and we still have a long way to go. In fact, we are at a cul-de-sac and that is going to lead to what happened to South Africa during apartheid. People must rise up, force change. [The book is] my way of reminding us that during apartheid, change took place because of ordinary people. They were the ones that got out, stood up and fought in the streets. They made the country ungovernable.”

The book, which he funded himself, features four sections. The first and largest portrays South Africa, beginning in the 1970s and ending with an image of Nelson Mandela at the funeral of Walter Sisulu in 2003.

It also features work he produced in Ethiopia, part of a wider project he undertook that considered the impact of conflict in Africa. Another section is a collection of the work he produced in Denmark, where he spent a few weeks in 1995 as an African photographer focusing his gaze on their society. The last section documents Badsha’s voyage to India for the first time in 1996, where he visited his ancestral home of Tadkeshwar.

[Funeral of ANC cadre Stembiso Nzuza, Kwazulu-Natal, 1994]

“I grew up listening to stories of the villages and, up until the mid-Sixties, meeting a few people from the villages who were visiting Durban,” he says. “When I got to Tadkeshwar, I was amazed at my ignorance. Meeting people on my daily walk through the small town, I saw how much people knew about me and events in my family, and the village network in South Africa and the diaspora scattered around the world.”

Badsha is one of those rare individuals who always finds the intimacy in his interactions. His approach does not differ whether he is photographing workers, community meetings or family members. His photographs are personal. Striking examples of this include the portrait of his daughter Farzanah, with her great-grandmother in 1978.

Another exemplary portrait is of a pensioner on Christmas Day, taken in Inanda in 1982. It is a classic portrait, the dignity in her gaze holding us and illustrating the simplicity of her home.

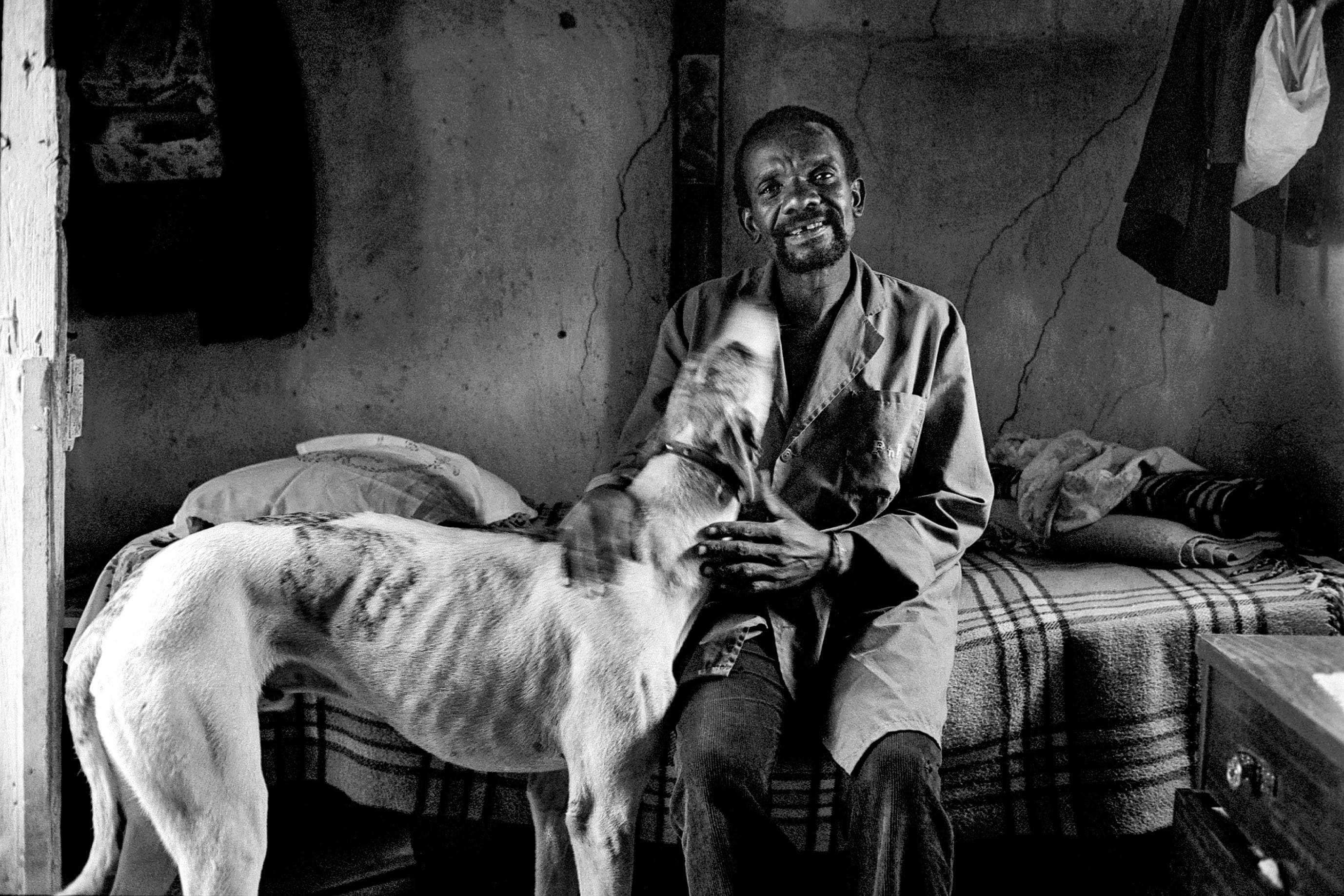

The photograph Badsha took of a man and his hunting dog in Inanda is also a great example of his thoughtful approach to his subjects. It is a beautiful and honest moment.

[Man with hunting dog, Inanda, 1982]

The importance of dignity, of the individual, features heavily in our conversation, underlying its importance to his work and its purpose.

“They were not just victims: they created, they were lovers, they were mothers and fathers, they were husbands, they were wives. They created their own spaces. They lived,” he says of his subjects.

“This defines who they are. Not like the one-dimensional people that the main discourse in South African photography has always been: that here are these poor, starving people,” he says.

Seedtimes reflects a life that has been lived, and seen, through bright, inquisitive eyes that are still amazed. I ask him how he feels now that the book is done. “I’m always someone that feels once it’s done, it’s done. I move on. Now I have to sell the damn thing!”

Proceeds of the book go to the South African History Online internship programme. It is available from omarbadsha.co.za