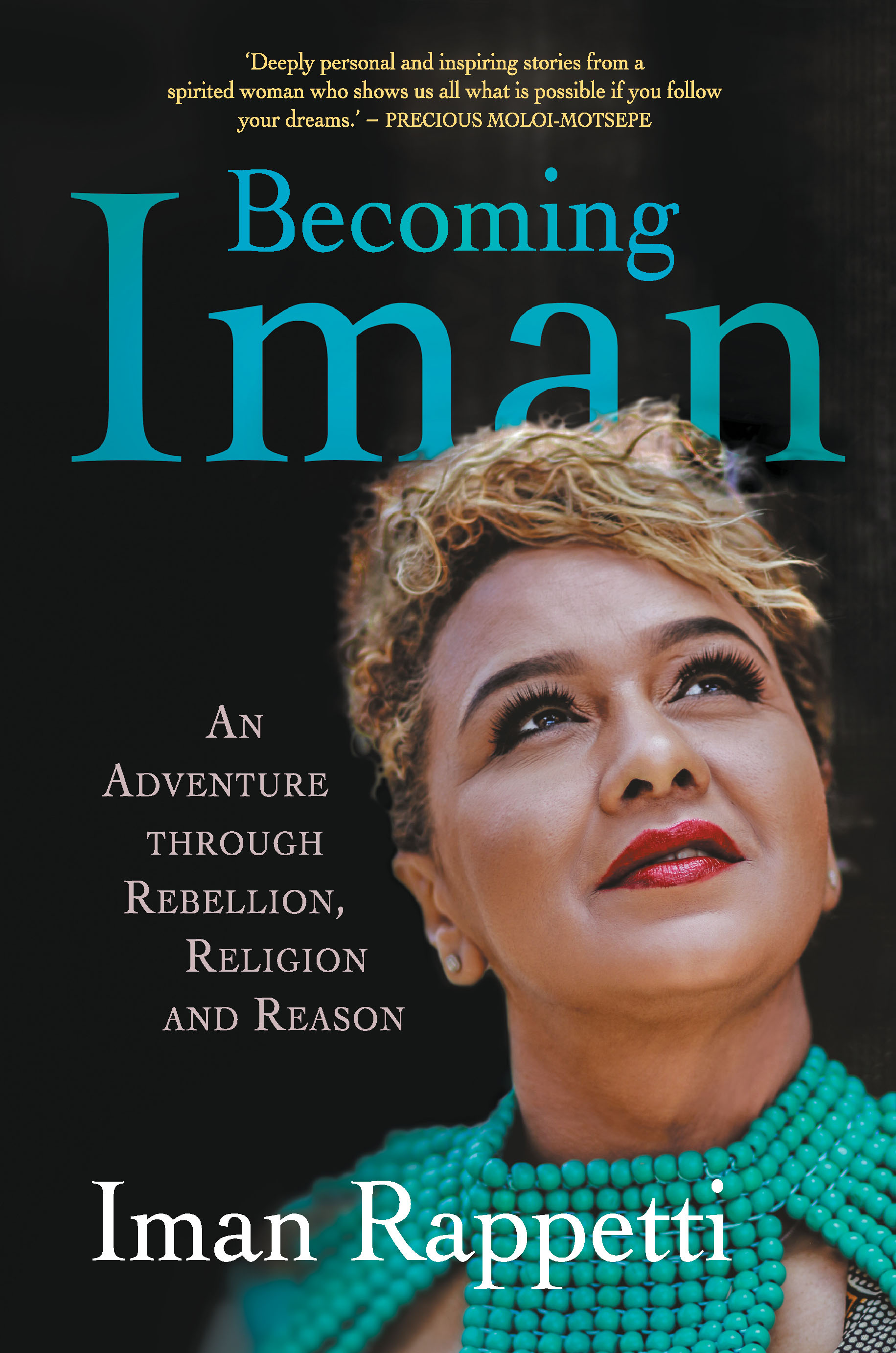

Multifaceted: Iman Rappetti was born to an Indian father and a coloured mother

The opening scene of my favourite musical, Rent, begins with Seasons of Love and a familiar piano riff. Characters gather at the front of the stage, arranging themselves in a straight line, as they collectively ask: “How do you measure a year?” Daylights, sunsets, midnights, cups of coffee, inches, miles, laughter and strife are all offered as possible units of measurement, before they settle on measuring life in love.

For writers, one way of measuring the passing of years that culminate in the experience of human life is in a memoir. Over the past year, the South African literary landscape has been enriched by the publishing of astonishing, brilliant memoirs that include Sisonke Msimang’s Always Another Country, Thuli Nhlapo’s Colour Me Yellow, Sara-Jayne King’s Killing Karoline and Siya Khumalo’s You Have to Be Gay to Know God.

Each of these books offers diverse and intersecting personal narratives, revealing as much about the authors as they do about what it means to be and become against a South African backdrop.

Iman Rappetti’s Becoming Iman enters this domain as a deeply vulnerable, achingly honest, hilarious and vibrant narrative of a life punctuated by difference and change. In a series of vignettes, she journeys from her upbringing as a mixed-race child in Durban’s Reservoir Hills to her religious conversion, her move to Iran and her return to South Africa, with a refreshing frankness and studied observations of race, religion and gender.

[Iman Rappetti’s memoir is a vulnerable, honest, funny and vibrant narrative from the journalist (Pan Macmillan)]

Each chapter holds significant moments, functioning as critical insights into the shaping of a life. On the surface, the memoir tells the story of how the young Vanessa morphs into Iman, the radio and television broadcaster and journalist known across South Africa.

However, this seemingly simple progression belies the many layers that both hold the narrative and give it weight, shape and depth.

Life, as we all discover, is not a progression that follows neat logic — we become who we are in tiny shifts along the same path. Change can be abrupt, forceful and even surprising. When we reflect on the journeys we’ve travelled, the difference can be so stark as to render all the people we have been almost indistinct from each other.

These people, all facets of our deepest selves, may have never been friends, sat in the same room or even held a polite conversation. Yet they all form part of who we are. Sometimes this change in personhood is marked by having a tattoo, moving across continents or adopting a new name. At other times, it barely registers on our radar, only becoming visible after the passage of large tracts of time.

I met Rappetti as a frequent guest on her Power FM radio show. As I walked into our first meeting, fairly new to the city, I was struck by her familiar accent. Later, it would frequently curve around a “what-kind stekkie”, as I entered the studio, and seemed instantly to collapse the distance between Johannesburg and Durban through our shared slang. It never failed to produce in me a nostalgic ache for home.

I felt the same ache years later as I read her memoir on a flight back from the Franschhoek Literary Festival, where we had reconnected. The book is peppered with meals I recognise, people I identify with and a vernacular that now sounds like poetry to me.

“Hawu, don’t vat me.”

“Where you vying?”

“Yoh, that stekkie is a GF!”

These are the voices of my childhood: the exchanges I heard outside my sister’s house in Wentworth, the slang we spoke on the streets, code-switching with finesse across contexts.

As experiences from the Western Cape continue to centrally define what it means to be coloured, reading about another way of being registered as relief and rapture.

There are multiple ways of being coloured, mixed race and even both, nestled into the corners of our country, often pulsing beneath more dominant narratives.

Rappetti captures a sensory experience that made me relish the smells and sounds of home. Sticky fingers after eating beans and trotters. Swirled hair, carefully kept silky under stocking caps. Being pulled from sleep and pushed into the routine of Saturday-morning cleaning.

It is a reminder of the importance of representation — of seeing people who share your experience in the lines of books, in images on screens and reflections in references.

In Becoming Iman, this recognition is familiar and familial and yet also profoundly different. One of the book’s strongest contributions is how it reveals that being mixed race is not simply a combination of the apartheid categories of black and white. Rappetti explores the contestation between her Indian and coloured roots, echoing experiences across the two communities that exist side by side yet still wrestle with tensions, stereotypes and bigotry that create vast distances between them.

She relates how her father was shunned by his wealthy family after marrying a coloured woman, and how this marked their lives in unalterable ways. She reveals how in a context where racial borders masquerade as clearly defined, mixed identities and different experiences are difficult to reconcile.

She writes: “My neither-here-nor-there-ness cheated me out of a solid identity. I was coloured in Unit 13 and Indian in Red Hill, and each social setting amplified the stigma of not being completely enough or worthy of either.”

She embraces all the aspects of what this mixed existence means as it pervades her metaphors and language, exploring the beauty and backgrounding the ugliness and pain.

A further strength lies in the way Rappetti writes about her conversion to Islam with compassion and colour, even as she now stands at a distance from this version of herself. It provides important insight into a world pervaded by the ugliness of Islamophobia.

Regular listeners to her radio show will find a familiar voice in the book: intimate, insightful and accessible. She writes as she speaks, with remarkable clarity and lush poetics. However, as fellow writer and journalist Rehana Rossouw comments: “Her writing is drop-dead gorgeous, but some of her sentences are so rich that they sag under the weight of her poetic words.”

But when it works, her sentences sing. There are moments when the leaps between chapters feel large, leaving questions about the spaces in between the scenes.These are rare, however.

The tone of the book is relatable, as her warmth radiates across the pages with sincerity and authenticity. Even when she is dealing with difficult matters — losing religion, divorce, domestic abuse, betrayal and prejudice — Rappetti does so with the humour, honesty and optimism that has become synonymous with her name.

But whereas the voice is familiar, the Iman who emerges might not be – this is the mark of great memoir: the creation of intimacy and a more profound sense of knowledge about the author. Rappetti shares pathologies and fears in her book, breaking herself open in ways that reveal her humanity, as she explores the effects of social conditioning, strict interpretations of religion, racial stereotypes and the complexities of desire within communities, with powerful resonances.

The journey in Becoming Iman is punctuated by the coexistence of joy and difficulty and the spaces in between, and it is one that Rappetti is committed to, in all of its intricacies and in the challenging introspection required to find peace and personhood.

Our experiences indelibly alter us. We are made by various moments along the trajectory of our lives. From birth to death, we shape-shift and shed skin as we shift across time. As Rappetti reveals, becoming is a strange and almost mysterious process.

In relating the many versions of herself, past and present, she is able to treat all with compassion, kindness and a gentle understanding.

The importance of this kind of personal work is expressed in the words of Joan Didion, who in Slouching Towards Bethlehem writes: “I think we are well-advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be, whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4am of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.

“We forget all too soon the things we thought we could never forget. We forget the loves and the betrayals alike, forget what we whispered and what we screamed, forget who we were.”

It is common knowledge that who we were shapes who we are and who we will become. We are a composition of all our experiences. In Becoming Iman we see:

The young girl who loved her father, and was wounded by witnessing him beat her mother.

The child who was “Vanessa” to her coloured mother and “Venesha” to her Indian grandmother.

The Living Waters Full Gospel church-goer attendee and the chador-wearing Muslim.

And finally, the sexually liberated woman and the successful journalist.

Different, intersecting and all Iman.