(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

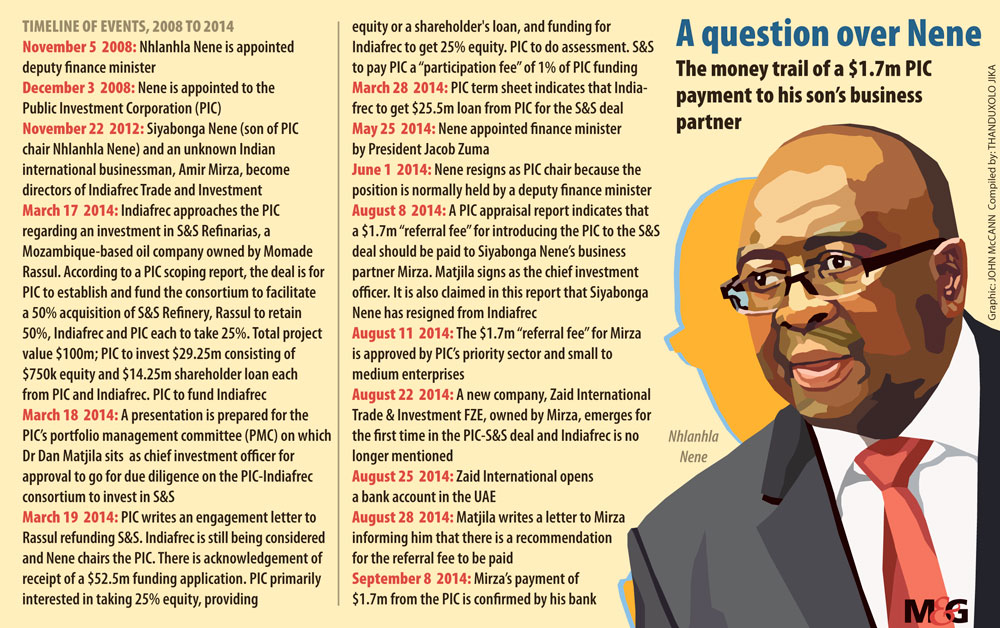

Siyabonga Nene asked the PIC to finance a huge investment in Mozambique. He didn’t get that for himself, but the state-owned fund manager appears to have bent over backwards to help his business partner —which included depositing millions into an offshore account

Twelve minutes’ drive from the Port of Nacala in northern Mozambique lies the 35-hectare industrial complex that Momade Rassul Rahim built. Behind a three-metre perimeter wall there is a palm oil refinery, soap manufacturing plant, office and staff accommodation blocks and a dozen or more warehouses.

It is here that on February 24 2014 a large consignment of imported motorcycles caught fire, gutting a warehouse and leaving a mountain of mangled metal parts.

Questions have since been asked of those bikes. Published research papers have linked them to the same people who allegedly ran a scam in which import duties on motorcycles were evaded by claiming they were for the ruling party, Frelimo, and that their petrol tanks had doubled up as vessels for trafficking heroin.

It may be premature to speculate whether Rassul was complicit in such crimes, although his arrest on allegations of money laundering, tax fraud and smuggling last year will add to the suspicion.

He did not respond to queries this week and has yet to stand trial.

South African civil servants, through their pension fund, came to be Rassul’s business partners and majority owners of S&S Refinarias de Óleos LDA, the palm oil refining and associated business he had built at that site.

The short answer of how this happened appears inthe records of the Public Investment Corporation (PIC), which state: “PIC has been approached by a South African company lndiafrec Trade & Invest (Pty) Ltd to establish and fund the consortium to facilitate a 50% acquisition of S&S Refinery LDA In Mozambique…

“Indiafrec … is the brain child of two young entrepreneurs, Muhammad Amir Mirza and Siyabonga Nene.”

The PIC is the state-owned investment manager of government employees’ pensions. Its chair at the time of Indiafrec’s approach was Nhlanhla Nene, then deputy minister of finance. Siyabonga Nene is his son.

After rumours about the deal started circulating last weekend, Nene Sr used his appearance at the Zondo commission of inquiry into state capture on Wednesday to state: “I deny that I have ever acted inappropriately with regard to any investments made by the PIC. I deny any and every allegation that I knowingly acted to promote any funding from the PIC for any business involving my son.”

His spokesperson, Jabulani Sikhakhane, later told the Mail & Guardian: “Minister Nene only became aware of his son’s involvement in Indiafrec’s Mozambique deal when his son, in a casual father-son discussion, mentioned that he and his business partner had run into problems with a deal they had been negotiating with the Public Investment Corporation. At no point did Minister Nene discuss the Indiafrec transaction with the PIC.”

He denied any conflict of interest, pointing out that the deal was of such a value that it did not require the approval of the board Nene chaired. “Conflict of interest would only have arisen if Minister had presided over a PIC meeting where Indiafrec’s funding proposal was being discussed… In any case, Indiafrec’s funding application was turned down.”

The details of Nene Sr’s knowledge and subsequent actions is still to be heard.

In the meantime, the available evidence suggests a picture of the PIC rushing eyes wide shut into a R1-billion investment that could only bring trouble, made not in the interest of government pensioners but founded on the need to gratify Nene Jr and his business partner.

At the sharp end of the PIC’s efforts was Dan Matjila, first as its chief investment officer and then as its chief executive, a position to which Nene Sr appointed him in December 2014, six months after becoming finance minister for the first time.

Relevant PIC motivations and transaction documents invariably bear Matjila’s signature —including when the PIC paid an R18.5-million “referral fee” into the freshly opened account of an obscure Emirati company, Zaid International Trade, represented by Mirza, Nene Jr’s business partner in Indiafrec.

When things fell apart between Mirza and Rassul, Matjila was still there, allegedly involved in negotiations to secure a $3.3-million settlement in favour of Zaid International Trade.

Nene Jr and Mirza did not respond to requests for comment.

The PIC said in a written response this week that “the suggestion that the investment was made to bestow patronage does not hold water”.

It said it was dealt with “in terms of PIC’s established investment process, which includes thorough due diligence and was approved in terms of the delegation of authority.

The assertion that Dr Daniel Matjila, as the chief executive officer, makes all the investment decisions must be dismissed. Investment decisions in the PIC are made by the relevant committees in terms of delegated authority by the PIC board.

“It is equally important to state that, at no stage —from the time when the application for funding was received until approval —did the then chairman of the PIC board, Minister Nhlanhla Nene, become involved [in] investment processes.”

Half to Indiafrec

But back to February 2014, the month of the burning bikes. That same February, PIC staff considered documents with a view to investing in S&S Refinarias, which was still building the plant, which would refine palm oil to produce edible fats and soap.

By the middle of the next month they put their signatures to a scoping report that envisaged acquiring 50% of the company by investing $29.25-million in it. Half of that stake would go to Indiafrec, whose participation the PIC would finance.

It contained the line, subsequently repeated in other PIC reports and motivations, about Indiafrec having “approached” the PIC with a request to fund the deal. It also said that Indiafrec was co-owned by Nene Jr and Mirza.

Company registration records show that the two men incorporated Indiafrec some 16 months earlier. Both were and remain directors. They also co-founded another company around that time.

Little is known about Mirza, an Indian citizen who appears to be in his early thirties and has given his address as a residential hotel in Fordsburg, Johannesburg.

Indiafrec out, Mirza in

In early April 2014, Rassul signed an “engagement letter” which the PIC had prepared. It explained that the PIC and Indiafrec were interested in acquiring 25% each of S&S Refinarias and outlined the next steps towards the potential investment, which now stood at $52.5-million.

Up to that point, Nene Sr was the deputy finance minister and PIC chairperson. The following month, May 2014, he was appointed finance minister. Although he would no longer be the PIC chair, it now answered to him as its sole shareholder on behalf of the state.

Sikhakane maintained this week: “The minister of finance is very far removed from the day-to-day business of the PIC and there’s no requirement for the PIC to report to him on investment deals that are being done by the PIC.”

Two-and-a-half months later, in August, the PIC’s formal approvals kicked into gear. Matjila signed an “appraisal report” motivating the investment to a PIC investment panel consisting of executives and directors, which approved it.

But now the deal structure was different.

First, the appraisal report contained a claim that Nene Jr “has since resigned” from Indiafrec, which appears untrue given that company records still reflect him as a director.

Second, it no longer envisaged Indiafrec acquiring a stake but rather Mirza personally. He, the PIC and Rassul with his wife would hold 33% each. The envisaged PIC investment had now grown to $62.5-million, which would go into loan finance and the PIC’s stake but not Mirza’s.

Third, the report motivated for, and the panel approved, the payment of a $1 726 500 “referral fee” to Mirza who now, rather than Indiafrec, got the credit for having “introduced the potential investment in the company”.

In short: Nene Jr and Indiafrec had been written out of the deal and substituted with Mirza alone —who would no longer have his stake funded by the PIC, but would get a very large fee supposedly for having introduced the PIC to the opportunity.

Nene Jr’s exit appears consistent with what a senior ANC leader said he had been told by Nene Sr. “He said his attention [about his son’s involvement] was drawn when he was deputy minister. He said he asked him to pull out of this thing.

“He said the relationship had nothing to do with the PIC, but he told the son to get out of it.”

The PIC this week initially commented that it did not fund Indiafrec because its “BEE [black economic empowerment] policy at the time did not apply to projects outside South Africa”.

It later supplemented the comment, saying: “We also wish to state that one of the other considerations in this specific transaction was a potential perception of conflict of interest, given that Siyabonga is related to the then chairman of the PIC board.”

But was the son’s exit real?

Events to follow, including his alleged participation in attempts to recover the $3.3-million Rassul settlement and the emergence of the obscure Zaid International Trade to receive the referral fee and payments, may cast some doubt on that.

R18m offshore

The PIC paid the $1 726 500 referral fee (R18.5-million then) in early September 2014, some weeks after the PIC investment panel’s approval.

This was after Mirza and Rassul had given written assurances that the PIC could also partner with Rassul in other business opportunities, a condition which appears to have been inserted to assuage internal concerns.

Large questions about the payment include:

Indiafrec had come to the PIC asking to be funded. It was not an independent party bringing a rare investment opportunity. Although the investment panel approved the fee, its minutes included this apparent reservation: “High cost … R17-million [sic] why should the PIC be responsible to pay that[?]”

The PIC commented that it was “disingenuous” to regard the payment as undue. “It is industry practice to pay referral fees in certain instances. PIC deemed it appropriate in this circumstance to pay a referral fee to Zaid International Trade and Investment for introducing investment opportunities in Mozambique which, at the time, PIC identified as a country with good investment prospects.

- Even if justified, why so much?

The fee was calculated as 1.5% of the total project value of $115.1-million rather than the PIC’s intended investment then standing at $62.5-million. The latter would have been a more rational measure as the PIC’s returns would be determined by the level of its investment, not total value.

Mirza invoiced in the name of Zaid International Trade and Investment, a United Arab Emirates “free zone” company with an account number that attached bank documents show had only just been opened. Emirati free zone companies, which had been used to great effect by the Guptas to launder money, are typically instantly registered, tax free and completely opaque.

Nene Jr had as much apparent reason to benefit as Mirza, because their joint company Indiafrec made the “introduction” in the first place. Zaid International’s opaque ownership as a free zone company does not help dispel concerns that he was to benefit too.

The PIC said: “With regard to the ownership of Zaid International Trade and Investment, the PIC understood this to be a company wholly-owned by Mr Amir Mirza.”

Sikhakhanesaid that Nene Jr had “no involvement” in Zaid International.

Mirza in, Mirza out

The referral fee having been paid, PIC staff got back to the actual investment.

That same month, September 2014, staff bounced a new structure around, one remarking in writing that “I have discussed this with Dr Dan [Matjila]. He is happy with the structure at the moment.”

He was referring to a breakdown that showed the PIC’s stake rising to 45% of S&S Refinarias, but its loan finance contribution decreasing to give it a total commitment of $53-million. The remaining 55% was to be held by a special purpose vehicle in turn held 60/40 by Rassul and Mirza, the former seemingly financing the latter’s stake.

The PIC investment panel approved the amended structure in October, after which the money started flowing: $18-million for the 45% shareholding in November and $35-million in loan finance by July 2015.

Soon, the intended special purpose vehicle was set up to hold the remaining 55%, Mozambican company records show. But there was a catch — the shares were divided between Rassul, his wife and a third Mozambican but nothing for Mirza.

PIC at the settlement table

A lawyers’ letter sent last year on Mirza’s and Zaid International’s behalf to Matjila states that “over and above” the referral fee, Mirza and the Emirati company “had an original entitlement to the allocation of shares” in the special purpose vehicle.

“For various reasons … this initial intention did not proceed and a settlement agreement was concluded to compensate our client for its exit from the project.”

The letter claims that although Rassul had originally promised Mirza $10-million to walk away from the deal, a final amount of $3.3-million was negotiated when Rassul, Mirza, Matjila and others met at the Protea Fire & Ice Hotel in Pretoria.

A settlement agreement, the letter said, was drafted by the PIC’s lawyers and signed in the presence of the PIC.

Why the PIC would have facilitated the settlement that, on the face of it, was a matter between Rassul and Mirza, remains unclear. It did not dispute the facts or comment on them.

The settlement agreement was signed by Mirza and Rassul on October 20 2015 and the former invoiced the latter, again giving details of the Zaid International offshore account.

Again there is the question whether Nene Jr was to benefit. Two confidential sources have placed him in at attempts to recover the money when Rassul failed to pay the full $3.3-million.

One, a PIC-linked source with direct knowledge, said Nene Jr was present when Mirza consulted lawyers about the issue.

When the due date for Rassul to pay up came and went in November 2015, the PIC —coincidence or not — very soon moved to put another $10-million in Rassul’s pocket.

Within two weeks, two further “appraisal reports” had been prepared motivating the purchase of a further 25% of S&S Refinarias from Rassul’s special purpose vehicle.

Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene was the chair of the PIC and the deputy minister of finance in 2014, when his son, Siyabonga, approached the state-owned fund manager with an investment proposal. Nene Sr used his presence at the state capture commission to deny any wrongdoing. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Finance Minister Nhlanhla Nene was the chair of the PIC and the deputy minister of finance in 2014, when his son, Siyabonga, approached the state-owned fund manager with an investment proposal. Nene Sr used his presence at the state capture commission to deny any wrongdoing. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

“The rationale,” the documents said, “is for PIC to warehouse the additional equity for strategic partners who will be appointed as the Management Company.”

This supposedly offered the PIC “the ability to support [the] Black Industrialists Programme”.

In January 2016, a PIC investment panel approved the purchase for $10-million, although minutes reflected concern about Rassul’s commitment to project, given that he was selling down his shares “within such a short period of time”.

The PIC this week denied that the further $10-million investment was linked to Rassul’s settlement agreement with Mirza, repeating that the rationale was to warehouse the extra shares for strategic partners who would be appointed as operating partner.

Owners of a lemon?

When the $10-million flowed to Rassul a few months later, government employees, via the PIC, became the proud owners of 70% of S&S Refinarias for a total investment, including the referral fee, of about $65-million (R950-million now).

Did the civil servants get value for money?

During the PIC’s approval processes for the investment, there were internal concerns regarding Rassul’s adherence to corporate governance standards and about managerial capacity at S&S Refinarias.

The investment panels set conditions including that two directors must be appointed to the S&S Refinarias board, that the PIC should appoint an independent chair and that the PIC should appoint chief executive and chief financial officers.

Only the first condition appears to have been met.

The commissioning and operationalising of the plant, first envisaged for late 2014 or early 2015, has been way behind schedule. The refinery was formally commissioned in December 2015 but in late 2016 feedstock for continuous production had still not been secured.

The PIC’s own assessment of the project’s performance in its schedule of unlisted investments as of March 31 2017 was bleak. It noted an 6.38% rate or return against an expectation of 24% and gave it an economic, social and governance score of only 20%, which it categorised as a “laggard”, the lowest category.

The PIC commented this week: “The investment in S&S Refinarias was done on the basis of satisfactory due diligence conducted by PIC and independent appointed professionals … At the time, there was sound commercial basis to invest in the project.

“However, subsequently Mozambique experienced a severe economic downturn, with the currency devaluing by more than 50%, power outages and flooding in the area in which the project is based.

“This exacerbated problems normally associated with early stage investments. PIC and its Mozambican banking partners have appointed a new operator. PIC is satisfied that economic conditions are improving and that, with the introduction of a new operating partner, the increased production capacity will yield good results.”

What the PIC did not say was that the new operator, Vamara Mozambique, is part of a multinational group unlikely to fit the “black industrialists” description used to justify the final 25% purchase — or that according to its contract with S&S Refinarias, Vamara will take 50% of profits, again reducing the PIC’s return.

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism, an independent non-profit, produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB supporter to help it do more.