Get the message? Westburys residents took to the streets to get the police to act against the violence wrought by gangsters. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Heather Peterson (46) left her washing machine running when she went to collect the report card of a 10-year-old relative at the Westbury Primary School last Thursday, according to residents familiar with the details of the day.

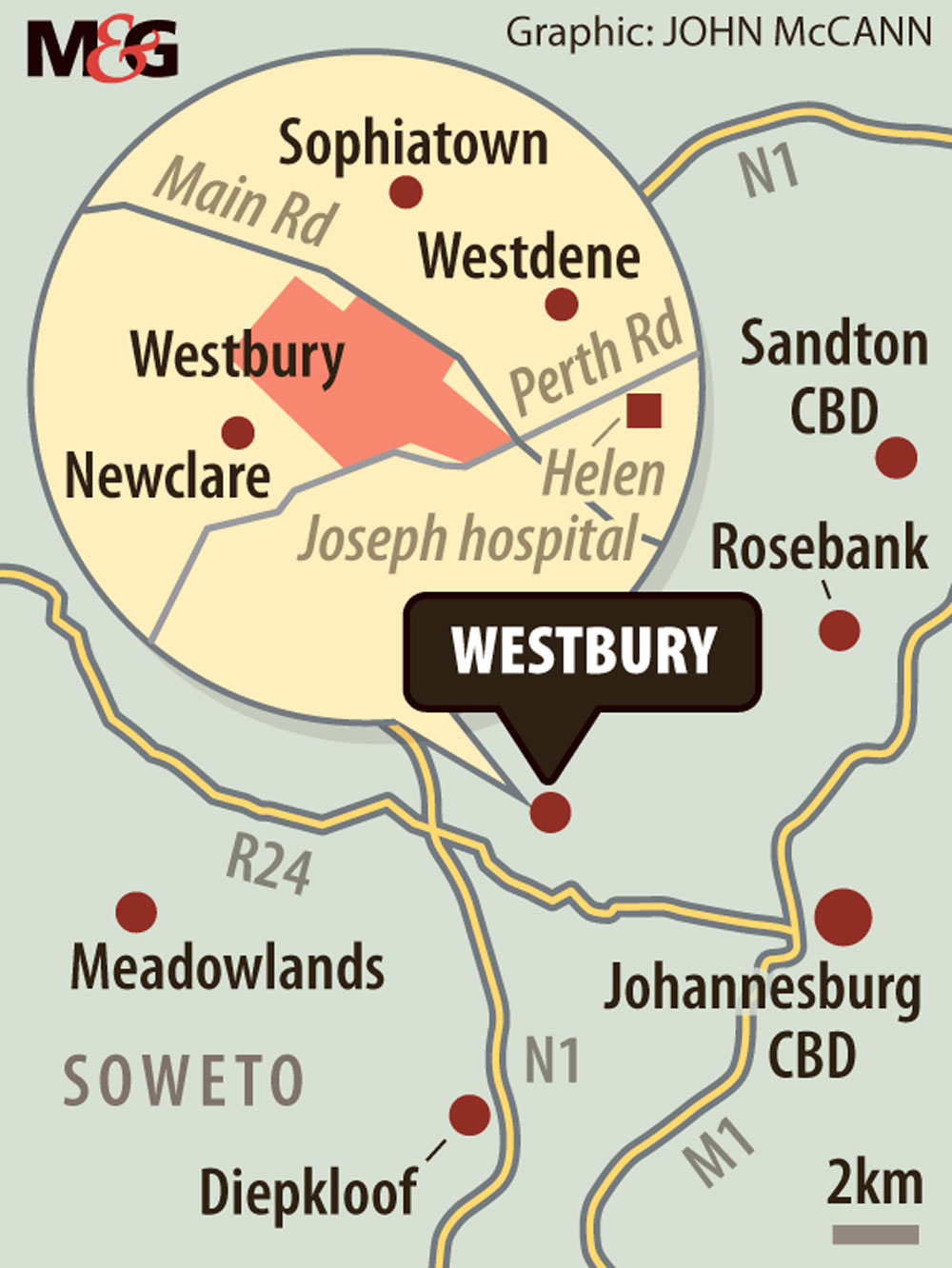

On her way back from the school, in an alley just metres from her home and down the road from the Rahima Moosa Mother and Child Hospital, Peterson and the child were caught in the crossfire of feuding gang members.

A photograph of Peterson, lying face down in a pool of her own blood, has been circulated widely among the residents of Westbury, on the edge of Sophiatown in Johannesburg.

She is wearing a doek and a plain tank top, the outfit of a woman cleaning her house or planning to nip out on a quick errand before continuing her chores. But Peterson never returned to hang up her washing.

Her death was the straw that broke the camel’s back, after years of gang-related killings in Westbury, according to residents.

A week ago, they took to the streets to protest against the ongoing violence.

Heather Peterson was shot dead at this spot in Westbury. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Abandoned

By Monday, the streets of the dusty suburb are covered in a film of black ash from burnt tyres. Yellow shopping bags, broken glass and bricks are strewn around. “I never knew Westbury had so many bricks,” one resident jokes.

The pedestrian bridge above the Rea Vaya bus station is where people gather to see the action but not get caught up in the chaos.

The day is punctuated by short bouts of conflict between police and protesters. But, once the commotion subsides, residents emerge from their houses with brooms to sweep up the mess.

From the relative safety of the bridge, a group of residents, mostly women, recount a list of violent killings that have left them feeling as if they are under siege.

“It makes me naar,” one woman remarks, her grey hair peeking out from under her headscarf. She asks not to be named.

Westbury residents hope for a better life. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

“But I will name the people that they need to arrest, even if they have to go to Durban and arrest them,” she says, taking a drag on her cigarette.

The women say Westbury’s main drug lords, who go by the names of Keenan and Finch, have fled to KwaZulu-Natal, where they are living it up while the rest of Westbury’s people have been left to fend off the police.

There is no love lost between Westbury and the police. On the bridge, Faye Faver explains why Westbury has lost faith in the authorities.

“Even if you bring evidence and the person is caught, they don’t even hesitate to tell them that this person saw you. Now you not safe. That’s the reason why people are not saying anything.

“For instance, with the incident last week, there are police from Sophiatown that know what happened there. Why are they not doing anything about it?”

Local leaders like Bishop Dalton Adams, who describes himself as the bishop who buries the most bodies, connects the violence that has enveloped Westbury to coloured people having been “gravely and tragically neglected by government. The coloured people have become the stepchildren of this country.”

Bishop Dalton Adams believes that the government’s neglect of coloured people lies behind the violence in the area. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Adams says the only way he was able not to get caught up in the violence of Westbury when he was growing up was because he was raised by a “praying mother”.

‘Praying mothers’

Carol Sallie is the person credited with organising the protests in Westbury.

She was teargassed on Monday and her voice is all but gone. But she says she won’t stop the fight because the women are tired of the violence.

“The gangsters are killing and raping our women and children, so we will continue even if we have to burn down everything — until our voices are heard.”

Sallie is a mother of three. She fears for her children’s safety and says that, whenever she hears of a child being kidnapped, she imagines one of her own in danger.

Police Minister Bheki Cele addresses the residents on Tuesday, explaining his plan to “clean the streets of gangsters”, including by deploying a special task team to patrol the streets and ensure that Peterson’s killers are brought to justice.

After the address, a group of women surround Sallie under the shade of a gazebo to seek her counsel. They ask her for direction on what to do next. Trust that the police minister will keep his promises, or take to the streets once more?

She isn’t bothered by being pulled at from all directions. “The people are not actually scared; they’re just waiting for someone to rise up and they will follow,” she says.

Community mouthpiece

Local radio station founder Joseph Cotty pulls Sallie to one side for a short interview. He puts her on the spot, asking whether she is satisfied with Cele’s response. She hesitates but eventually answers in the affirmative.

Fresh out of university, Cotty was an engineer at MNet but saw the need for a “mouthpiece” in the community in which he was born and raised. He left his job and joined forces with local leaders to start Kofifi FM in 2010.

Joseph Cotty of Kofifi FM interviews Carol Sallie, who helped organise the Westbury protests. A municipal worker (above right)cleans up the mess at a Rea Vaya bus station created during the protests by residents. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Kofifi is a nickname for historic Sophiatown where both of Cotty’s parents lived before they were banished from their home during the forced removals in the late 1950s.

Cotty says there was more order in old Sophiatown than there is in Westbury today. “The living was better than what it is now. People were protected, you must understand, under the apartheid government and police.”

Westbury needs the government to ease the residents’ seething anger, he says. This anger has taken on a distinctly racialised dimension. “The government must tone down the feelings that this is only done to the coloured people.”

In the early hours of Tuesday morning, Gatvol Capetonian co-founder Fadiel Adams and a small delegation flew to Johannesburg. His organisation has gained traction by advocating for what it describes as “Cape independence”.

Flanked by members of Indigenous First Nation Advocacy South Africa, Adams says they are there to show their support for Westbury’s people and played no part in precipitating its shutdown.

But many coloured people in the Western Cape have rejected Gatvol Capetonian’s vision.

A representative of the organisation, who was attending an anti-gang protest in Bonteheuwel, Cape Town, at the end of August, was allegedly chased away by residents. They said they did not want to be associated with the group because of the racial undertones of its messaging.

Cotty says Westbury is actually a diverse community.

“We don’t want to have a situation where people are going to now feel that they are not safe in their own area,” he says. “We want it to be the same like it was in Sophiatown, where everybody felt ‘this is our place’.” — Additional reporting by Michael Abrahams