(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

In the jobs summit’s framework agreement’s 84 pages and 12 798 words, “the fourth industrial revolution” is mentioned just three times.

The first time it occurs is in reference to the strategy and principles overview. It then appears twice more when noting the importance of producing the right skills to take advantage of fast-changing technologies associated with the term. These include artificial intelligence, nano- and bio-technology, 3D printing and quantum computing.

The agreement was signed at President Cyril Ramaphosa’s jobs summit in Midrand last Thursday.

Overall, the summit made little mention of the need to equip students and workers with the skills required to be competitive in South Africa’s job market.

Business Unity South Africa president Sipho Pityana raised this issue during the summit, saying the government is not addressing the disruption caused by these technologies in a systematic and meaningful way.

“With the advent of electric cars, what’s the future of petrol attendants? Like the Luddites of 19th-century Europe, the cab drivers of today who see enemies in the Uber drivers are in fact assailing their future allies in the coming struggle against driverless cars,” he said.

“Part of the preparation entails reforming of our education system to deliver suitably skilled workers in the numbers required. We are currently battling technology illiteracy, a shortcoming which makes many of our people unemployable in the rapidly growing gig economy.”

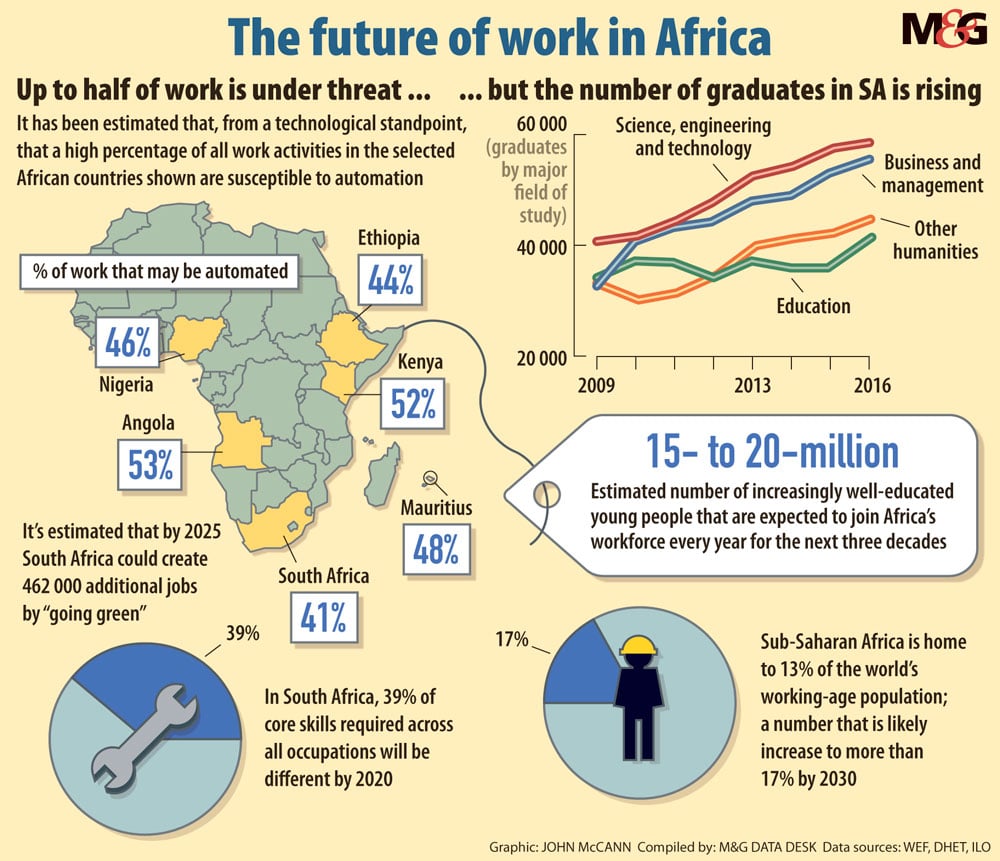

This should be of concern to South Africa. The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs and Skills in Africa analysis, which was published this year, found that in South Africa 39% of core skills required across all occupations in 2015 will be different by 2020.

According to the research, large numbers of employers are citing inadequately skilled work forces as a major constraint to business expansion. “Sub-Saharan Africa is far removed from making optimal use of its human capital potential and under-prepared for the impending disruption to jobs and skills brought about by the fourth industrial revolution,” according to the report.

Although the fourth industrial revolution may replace current jobs, it could also create new ones. Professions needing complex problem-solving and critical thinking such as artificial intelligence engineering and data science are in demand.

Stella Ndabeni-Abrahams, the deputy minister of telecommunications and postal services, ambitiously proposes to train one million people to master these skills by 2030.

The director of the Centre for Economic Development and Transformation, Duma Gqubule, says the idea of technology replacing workers has been going around since the third industrial revolution and it’s not a real threat. “It’s not a done deal that the fourth industrial revolution is going to replace jobs.

“When you get new technological advancements, it creates more productivity because you’re working more. It’s a cycle of ever-increasing productivity in the economy, and productivity means more income for you, which means more growth for the economy.”

According to the department of higher education and training in 2016, 59 125 people graduated with degrees in science, engineering and technology.

This sector has been the most popular and fastest growing since 2013.

Business and management is the second-most popular field of study, with 56 364 students graduating in the same year. This is followed by humanities (45 480) and education (42 107). Gqubule says, contrary to popular sentiment, most graduates find work. “The unemployment rate for graduates is about 6%. The country average is about 27%. So having a degree reduces the likelihood of you being unemployed.”

He says the economy will only be able to accommodate the employment-focused projects proposed in the agreement if the economy grows.

It’s a popular narrative today that people with low-paying jobs are becoming increasingly redundant. Technologies such as advanced machinery and artificial intelligence are automating tasks that previously required more costly human labour.

Yuval Noah Harari, the author of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, describes this susceptible group as the “useless class”. In an article published by The Guardian in 2017, he wrote: “The crucial problem isn’t creating new jobs. The crucial problem is creating new jobs that humans perform better than algorithms. Consequently, by 2050 a new class of people might emerge — the useless class. People who are not just unemployed but unemployable.”

The issue, therefore, isn’t that South Africa is not producing the necessary skills. It’s not producing enough of those skills. The country is struggling to accommodate the 27% unemployed — the class that is at risk of becoming “useless” in a modern economy.