File photo: In two recent incidents, staff in Delft were threatened by extortionists, the Western Cape standing committee on social development heard on Friday. (David Harrison/M&G)

It started with just one police officer but then more formed a crowd around her. As they forced her to the ground, with bursts of stun grenades exploding in the background, Henriette Abrahams saw their stony faces looking down at her. When they pulled her to her feet, six pairs of arms tightly coiled around her body, she continued to resist the arrest.

“Fok them,” Abrahams said as the police marched her to their van.

It was September 25 and Abrahams had been leading a protest against gangsterism in Bonteheuwel. On that day, the residents of the Cape Flats had attempted to shut down major arterial roads in their areas to protest against the violence.

The shutdown movement began at the end of August in Cape Town and has spread to areas rocked by gang violence in Gauteng.

The slogan on Abrahams’s placard read: “The power of the people is stronger than the people in power.”

She knows this first-hand.

She saw it at the funeral of Anton Fransch 29 years ago on a mournful day in Bonteheuwel. Fransch was just 20 years old. He had been a commander in Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) and he was killed after a seven-hour gun battle with police in Athlone, Cape Town, where he was hiding.

His shattered body was found inside the house. The police claimed he had committed suicide but a neighbour, Basil Snayer, told the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that he had seen a police officer throw something into the house moments before the explosion. Another freedom fighter in Bonteheuwel had died a violent death.

Abrahams had seen it many times before she stood at the front of Fransch’s funeral procession. A photograph by Omar Badsha shows her standing straight, with the coffin behind her, the side of her right hand touching the corner of her eye in a salute. She was 19 years old and the only woman close to the coffin.

Henriette Abrahams at the funeral of Anton Fransch, killed during apartheid. (Omar Badsha)

By that time, Abrahams had been arrested 14 times and, in her matric year, she had spent five months in detention. She had started her political education with Fransch and Ashley Kriel, the beloved MK martyr of Bonteheuwel, at the Bonteheuwel High School.

“Since the age of 13, I have been conscientised into the movement,” she recalls.

Eventually she would become a member of the United Democratic Front (UDF) and then the ANC. When Kriel, Fransch and others — the top-tier leadership of the organised structures — left the country to train with MK, Abrahams was among those who rose up the local leadership ranks.

“As Bonteheuwel in the Western Cape, we were quite a hot spot for [minister of law and order] Adriaan Vlok and all of those people. We had a very militant history. Some of our people left and joined the ANC in the camps. Some of our people stayed, like myself.”

Years later, she married and left Bonteheuwel. But she returned when she divorced, deciding to leave her only child, a son, with his father because Bonteheuwel is too dangerous to raise a young man.

This is what her fight now is about. The gangsterism and drug addiction have become intolerable and Abrahams has had enough.

“Today, we are the parents and the grandparents of our youth being shot and killed on our streets. We are the parents and the grandparents of these drug-addicted children. We are the parents and the grandparents of our little girls being raped,” she says.

“We have a consciousness as parents because of that time that we were in our youth, and we have the organising and mobilisation tools to organise for people’s power. And that I think is what government must realise.”

The militant priest

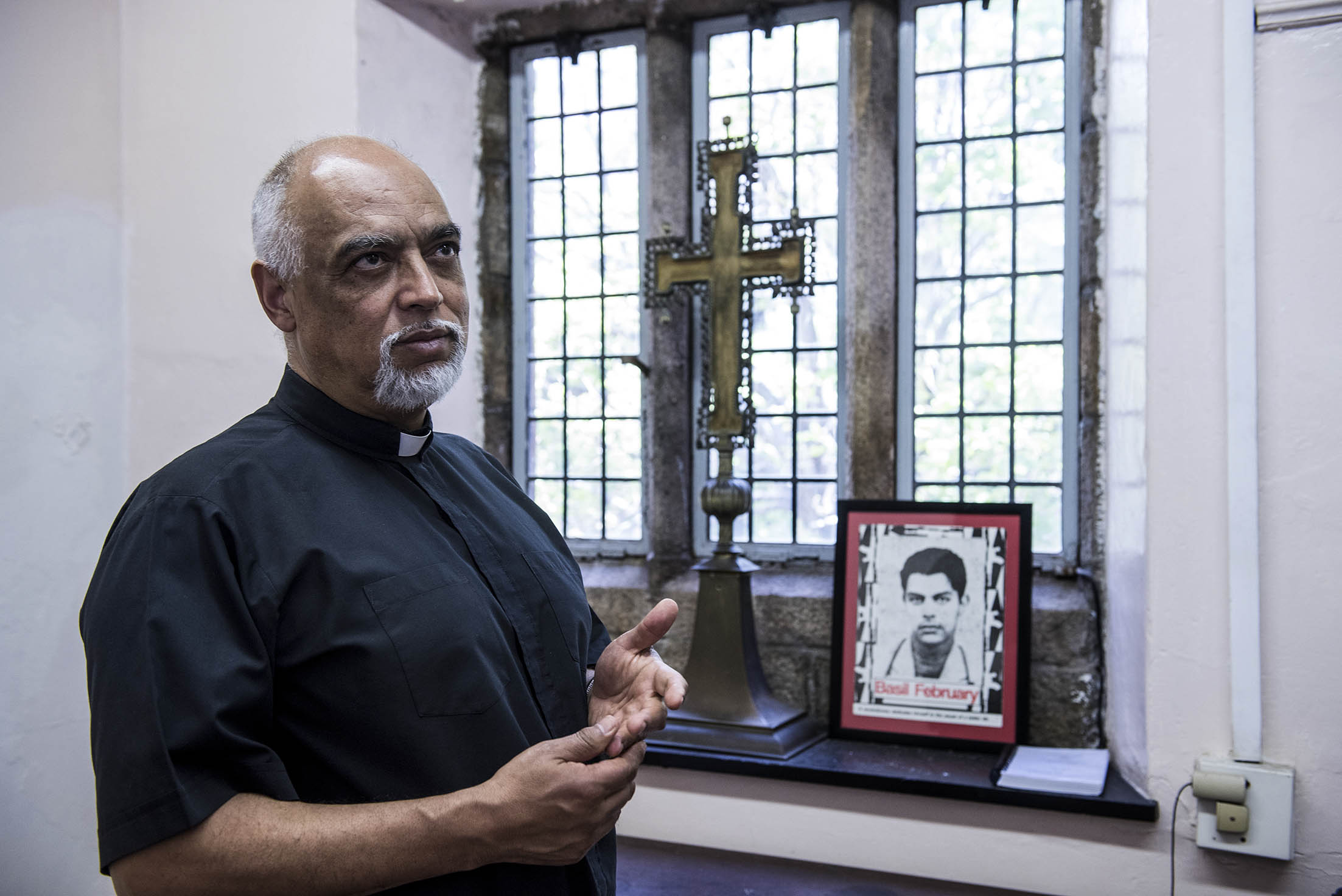

Father Michael Weeder is 77km from Bonteheuwel, in the Overberg town of Botrivier in the Western Cape. It has been two weeks since the video of Abrahams’ arrest went viral, catapulting her as a heroine of the anti-gang movement. He still feels inspired by her activism.

Michael Weeder is now dean of St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town. (David Harrison)

“She never walked away from Bonteheuwel,” he says.

Weeder, who is the dean of St George’s Cathedral in Cape Town, was asked by leaders on the Cape Flats to explain the plight of people living in gang-dominated communities to Police Minister Bheki Cele. He was later asked to facilitate a follow-up meeting with Cele in the Cape Town suburb of Kensington where, in August, the first shutdown took place.

Weeder is easy-going and laughs at himself, describing himself as a “bourgeois priest” with an “anarchist” attitude. At one time, however, he may have been described as a militant priest. In the 1980s, Weeder was a member of MK. He hid Tony Yengeni, the MK leader in the Western Cape, in his house in Factreton, an area that today helped to serve as a catalyst for the shutdown movement. It was the first gang-ridden area to shut down in protest with Kensington.

For a time, Weeder kept some of his activities with MK a secret from Archbishop Desmond Tutu. But when Yengeni was arrested, he told Tutu and asked whether he should leave the country, fearing Yengeni would name him under torture.

“I had no illusions of being the Che Guevara of the church because, whenever I met these young umfundis [students], and even Tony, I would pray with them. They would talk to me,” Weeder says.

Tutu advised Weeder to leave. He stayed in London, but returned to South Africa when he realised Yengeni had kept him safe from the Security Branch. On his return in 1988, Weeder said the church sent him to Ashton, a farming town in the Western Cape, to “cool down”.

But he didn’t really cool down. In 1990, Ashton rose up. Mandela was released and, as a young black priest, Weeder was enveloped by the growing resistance against the state. Locals wanted to occupy the municipal offices. A group of people marched to the town clerk’s offices, but it ended quickly. Weeder, who was not at the protests but heard it was coming to a premature end, went to meet the activists.

“I hear all the protests died down because the town clerk said, ‘You have no permission to be here, please leave’. And so the revolutionary insurrectionists leave,” Weeder says with a small laugh at the memory.

“When I come, I say no, we must sit down. I told them, when they beat us, don’t run, just stay. There’s about 100 people at first,” he says.

The first volleys of teargas came. Five defiant people were left — Weeder, a high school pupil from Zolani township and three women. As they sat, unmoving but afraid, the police threw another canister.

“The sergeant drops the teargas can and it bounces, and there’s a young laaitie that comes and he’s got woollen gloves with the fingertips cut off. He catches it and he tosses it into a pond. You just see how the goldfish pop up dead, their white bellies are pointed up,” he says.

The cops issued another warning, and Weeder encouraged the protesters to stay strong, not to move.

“I say to the women, ‘the teargas hurts you when you panic. When the teargas comes, just take shallow breaths and close your eyes and stay in the darkness there. You will pass out, you won’t die’.”

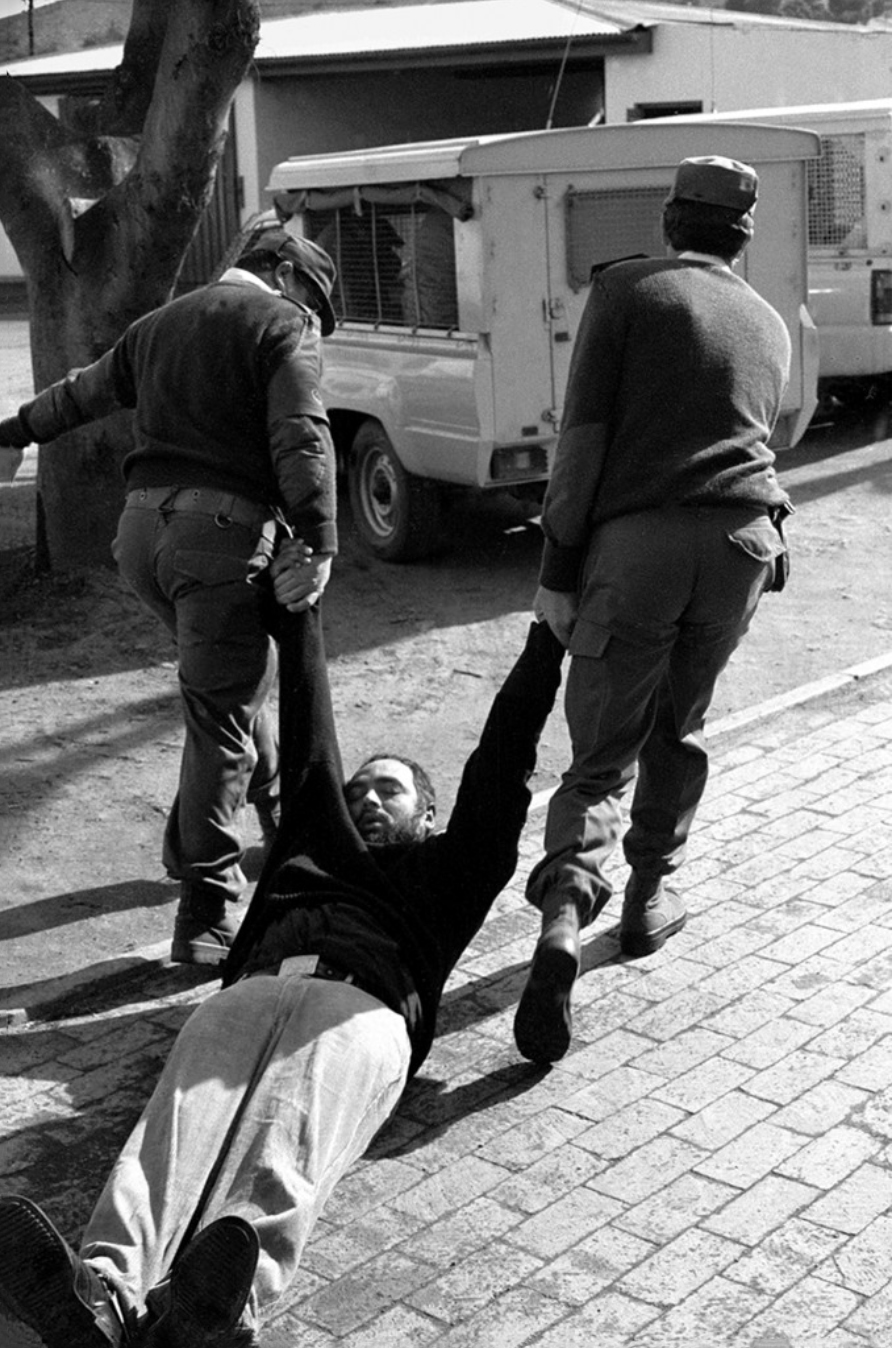

The police threw another canister. Weeder passed out and was dragged by police to their van. Weeder’s beard is now almost completely grey and his hairline has receded. But still he is called upon to be a peace-broker.

Reverend Michael Weeder was tear-gassed for his activism in 1990. He is now called on to be a peacebroker. (Benny Gool Archive)

He is from Cravenby and Elsies River, spending some of his formative years in a backyard with his mother, a woman who proudly embraced her Khoi ancestry. Their former neighbourhood, Elsies, has been overwhelmed by gang violence.

For Weeder, the gangs are spurred on by capitalism, poverty and what he describes as a lack of cohesion among coloured people because of the annihilation of the Khoi. He argues that younger generations do not have a sense of belonging and the gangs have taken advantage of this.

“When gangsters come and they have got their slogans and their rites of initiation, it gets a lot of our young people into a sense of belonging; even if it’s not an initiation that brings you into a community, it’s an initiation that isolates you from a community.”

But Weeder is careful — he acknowledges that gangsterism isn’t a coloureds-only problem. Groups such as Gatvol Capetonian have sought to appropriate the shutdown protests in the name of a coloured nationalism, arguing that they — as descendants of the Khoi — are the first nation and the rightful heirs to the land.

“It’s like they are saying ‘we are Africans with more rights than you have’,” Weeder says.

The youth congress activist

Anthony Phillip Williams, a leader of the Gauteng Shutdown Co-ordinating Committee, says he has been working closely with Gatvol Capetonian.

The protests that led to the shutdown movements in Gauteng started in Westbury, Johannesburg, after Heather Peterson was killed in the crossfire as gang members shot at each other. Residents began the protest but Williams, who lives 16km from Westbury, has tried to claim some credit for the protest, and others happening around the country.

He was involved in the Riverlea Youth Congress (RYCO), a youth formation of the ANC in the 1980s. He says he remembers being “smacked silly” by the notorious Security Branch officer Seth Sons, and attending meetings at the house of Shirley van Wyk, poet Chris van Wyk’s mother.

One of his former comrades says he was “very active”, another says “he was there”, whereas a third claims Williams was only a “supporter”. But Williams has furiously defended his role in the struggle.

He has not been without controversy since those days, however. Last year, Gauteng education MEC Panyaza Lesufi branded Williams and others racist because they rallied against children in Eldorado Park being taught by a black teacher. They demanded a teacher who is coloured.

Williams attributes gangsterism to the coloured people’s loss of identity, though he disagrees with Gatvol Capetonian that everyone from the Eastern Cape who came to the Western Cape after 1995 should be purged from the province.

He says being called coloured is wrong and people should instead identify themselves as KhoiKhoi. The genocide of the Khoi by colonialists, Williams says, meant that coloured youth don’t know who they are and are apparently now biologically predisposed to a loss of identity.

“This has been transferred genetically from generation to generation and that’s the reason why people don’t want to confront this cultural genocide and the misappropriation of who they really are,” he says.

“There is this anger and they don’t understand where it comes from. They don’t know why it is so easy for one to take a knife and stab the other one. They don’t understand because it is genetically infused in them and transferred,” he states.

But his views are not as popular as he would like.

The UDF and Cosaw member

Roegshanda Pascoe, a member of the shutdown movement, disagrees vehemently with Williams and Gatvol Capetonian.

“They are in denial,” she says. “The formation of gangsterism came when our people were in prison as a result of the racial segregation.”

Pascoe became active in the UDF in Manenberg, Cape Town, while she was at school. For her, political education at a young age helped her to make sense of the deeply traumatic home she grew up in and her community as it is now.

Pascoe was tired at a young age. When she was 10, she sat on a pavement on a street in Manenberg. She was waiting for a bus to come so she could throw herself under it.

Then a friend saw her sitting there. The little girl led Pascoe to the Moravian crèche, where her political education would soon begin. She found friends there and soon became active in the UDF.

Her foremost home became the Congress of South African Writers (Cosaw), which aimed to combat inequality in the apartheid education system. But it was difficult. Pascoe’s maternal grandfather was a “staunch” National Party supporter. When a letter arrived at the house from Cosaw, he accused her of being a communist.

“He literally phoned the police. I ran away for a few nights,” she says.

But she came to understand that the ills that traumatised her family were the result of a political system that left them dispossessed, poor and treated as inferior. Her great-uncle was an alcoholic whose land in Retreat was taken “by the Boers” in exchange for alcohol, she says.

The power hierarchies she saw then shape how she sees Manenberg today. She does not believe that gangsterism is only in areas where the population is predominantly coloured. Instead, she sees it as a capitalist phenomenon, where the hunger for money and competition for resources leads to people being killed.

For Abrahams, it’s a shame that ideas of nationalism and first nation have seeped into the protests. Justice is what the fight is about.

“It’s sad that the majority of communities in the uprising is a bunch of coloured communities because now people are seeing it as a race issue. It’s not a race issue. For us, it’s a working-class issue. The working class, regardless of your race, has been compromised,” she says.