Unhu: Through telling a story, author Tsitsi Dangarembga looks at womens varying views and and the dynamics between them

“Who is that one?” a girl shouts.

“That’s a murungu,” answers another.

“No it’s not. That’s a person,” the girl says.

These children have no idea who Tambudzai Sigauke is, arriving at her village after many years’ absence. She is driving a purple double-cab Mazda, and is so changed that not even her mother knows who she is at first. As recognition dawns, her mother, shrunken with age and gnarled by arthritis, observes tartly, once the provisions she has brought have been unloaded: “Finally, Tambudzai, now you have stopped eating everything you get alone.”

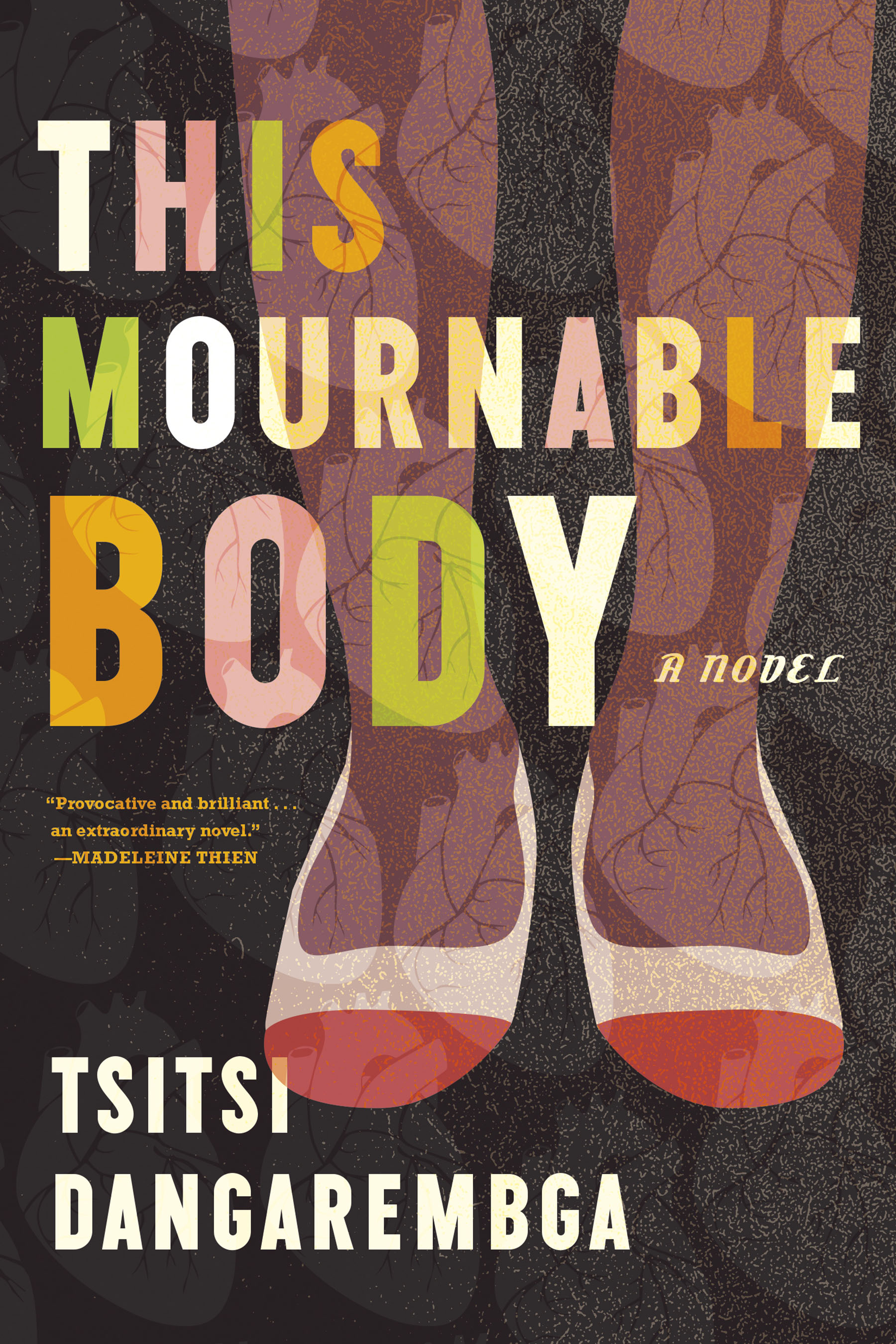

Those who have read Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions and The Book of Not, prequels to This Mournable Body, will remember Tambudzai, protagonist and narrator. In Nervous Conditions her voice was cool and plain, infinitely poignant as she recounted how she got herself to school. And her struggle against patriarchy, which was manifested in her favoured, spoiled brother (whose death she did not mourn — that famous opening sentence); in her beloved, respected headmaster uncle, Babamakuru; and her feckless father, who had to be humoured despite his genial uselessness. And perhaps in her mother’s complicity. In Nervous Conditions she was assisted by her irrepressible, clever cousin, Nyasha, one of the female relatives who form her thinking.

In This Mournable Body Tambudzai is in her 30s, and she again narrates her story herself, but in the second person, an interesting distancing of herself from herself, which reflects the divisions in her being.

Here Dangarembga’s writing is mature, less formal, vibrant and effortless in the complexity she layers into events and characters. She is often darkly funny and always deeply serious. The title of her novel was inspired by Teju Cole’s 2015 essay Unmournable Bodies, in which he commented on the grief and outrage in Paris after the attack on the French satrical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, noting that victims of violence in Africa were never given the same amount of attention.

Tambudzai, so full of ability and promise in Nervous Conditions, now goes through a period of suffering, which includes a stay in a mental hospital. Although she is still focused on her personal success, she gives up a well-paid job in an advertising agency, where she has had enough of being exploited and unrecognised. She takes a job as a biology teacher, but is infuriated by the bornfree girls she teaches, who are more interested in smoking, drinking and middle-aged men than in applying themselves to getting an education.

In her darkest hour it is the women of her village and her family who come to her aid, but eventually there will be a price. Dangarembga takes time to create these many female characters. In these harrowing times after the Chimurenga there are three widows and one lower-ranked wife of a polygamous politician, as well as female soldiers returned from war zones. They are managing to survive in Harare; politics is obliquely referred to in the milieu in which life has to be lived. Perhaps in these women Dangarembga brings us several mournable bodies. Most buoyant but not unscathed is Nyasha, now returned from Europe with two degrees, a white husband and two children. The first time she goes to Nyasha’s house, Tambudzai observes; “Your cousin begins to hum with the air of an empress returning to her fort after battle.”

The women war vets include Tambu’s Aunt Lucia, younger sister of her mother, as well as Kiri, from a neighbouring village, who takes news of Tambu home and brings a gift from her mother, a sack of home-grown and home-ground mealie meal. Tambudzai cannot bring herself to fetch it from Kiri, nor, once she has it in her own room, can she bring herself to cook and eat it. This symbol of her mother’s concern, uncompromising and plain, like her mother, torments Tambu and follows her even when she thinks she has left it behind. At one point she says: “You should have eaten it, you reprimand yourself, cooked your mother’s love … and taken it into your body. In this way you would have made a home wherever you were.”

In this novel Dangarembga deals less with patriarchy and more with the manifestations of feminism and the solidarity of women.

As a minor theme she also addresses whiteness, and “the Englishness” Tambu’s mother so abhorred in Nervous Conditions. She integrates three white characters into the plot: the widow Riley, a pitiable old white woman abandoned by her children who, in her confusion, insists Tambu is her daughter; Leon, Nyasha’s husband brought from Berlin with his different attitudes to money and work; and Tracey Stevenson, Tambudzai’s frenemy from school days, the ad agency and then her boss at Green Jacaranda Safaris. It is the whole way of being of the West that brings so much painful conflict to Tambudzai.

When the game farm owned by Tracey’s family and on which Tambu leads her ecotours is taken over by “war vets”, Tracey pushes Tambu to set up a new tour in her home area. This is what has brought Tambudzai back to the village, in her ostentatious vehicle. She is relieved to find that her mother is well disposed to the tourism idea.

Although it will bring opportunity and money, it is still something that has to be carefully negotiated. Tambu does her best, but Tracey imposes a demand relating to women dancing with bared breasts for tour groups. This is too much for Tambudzai’s mother. Refusing to be photographed with Tambu, she grabs an expensive German camera and flings it by the strap into a mango tree.

“How dare you,” she screams, although the visitors cannot understand her. “You want to laugh at my child when you are back home because her mother is a naked old woman.”

This dramatic and cathartic scene is not the end. Tambudzai finds she has much to learn “concerning the unhu, the quality of being human, expected of a Zimbabwean woman and a Sigauke, who has many relatives who either served or fell in the war”. This leads, after a few months of tears and penance, to a satisfying, but not simple, resolution of the novel. And it answers the question about whether she is still a person, despite her education and her aspirations.