Afro-modern literature reflects the pluralities that this generation of Africa's emerging writers live with. Photo: Delwyn Verasamy

I encountered the term Afro-modern at the Open Book Festival in September when Cape Town was shedding those excess layers of winter. Coined by Nigerian writer Pwaangulongii Daoud in his story Africa’s Future Has No Place for Stupid Black Men, the term resonated with what captured my mood for 2018.

The story won the 2018 Gerald Kraak award and was published along with other stories and photographs exploring gender, social justice and sexuality in an anthology titled As You Like It.

What is exceptional about the Afro-modern is its radical unsettling of being a theory or a movement. It is that bold generation, as Daoud puts it “We are open space: Africa’s newest genre.”

His story details a gathering of the African intelligentsia who are “neither Afro-romantics nor Négritudes. They are not critics and insulters of white people or the other kinds of craps. Afro-moderns are interested in a non-romantic view of Africa. That’s how they hope to see it well, and thereby recreate it. That’s how to create its curricula, its new politics, its new arts and aesthetics, its new business, its new industry, its pluralities.”

Daoud articulates a rebirth of the African personality, put forth by Pan-Africanists and the multiple versions of it that did not trigger action in the eyes of those distracted.

Perhaps you are climbing up your first mountain. Maybe you have reached the zenith only to discover that there millions of mountains surrounding what you have overcome. But no matter in which direction you gaze, the idea of genre and the persistent need to defy genres is overflowing in every valley. Questions of where do you come from, how fixed or fluid is your identity, where are your papers?

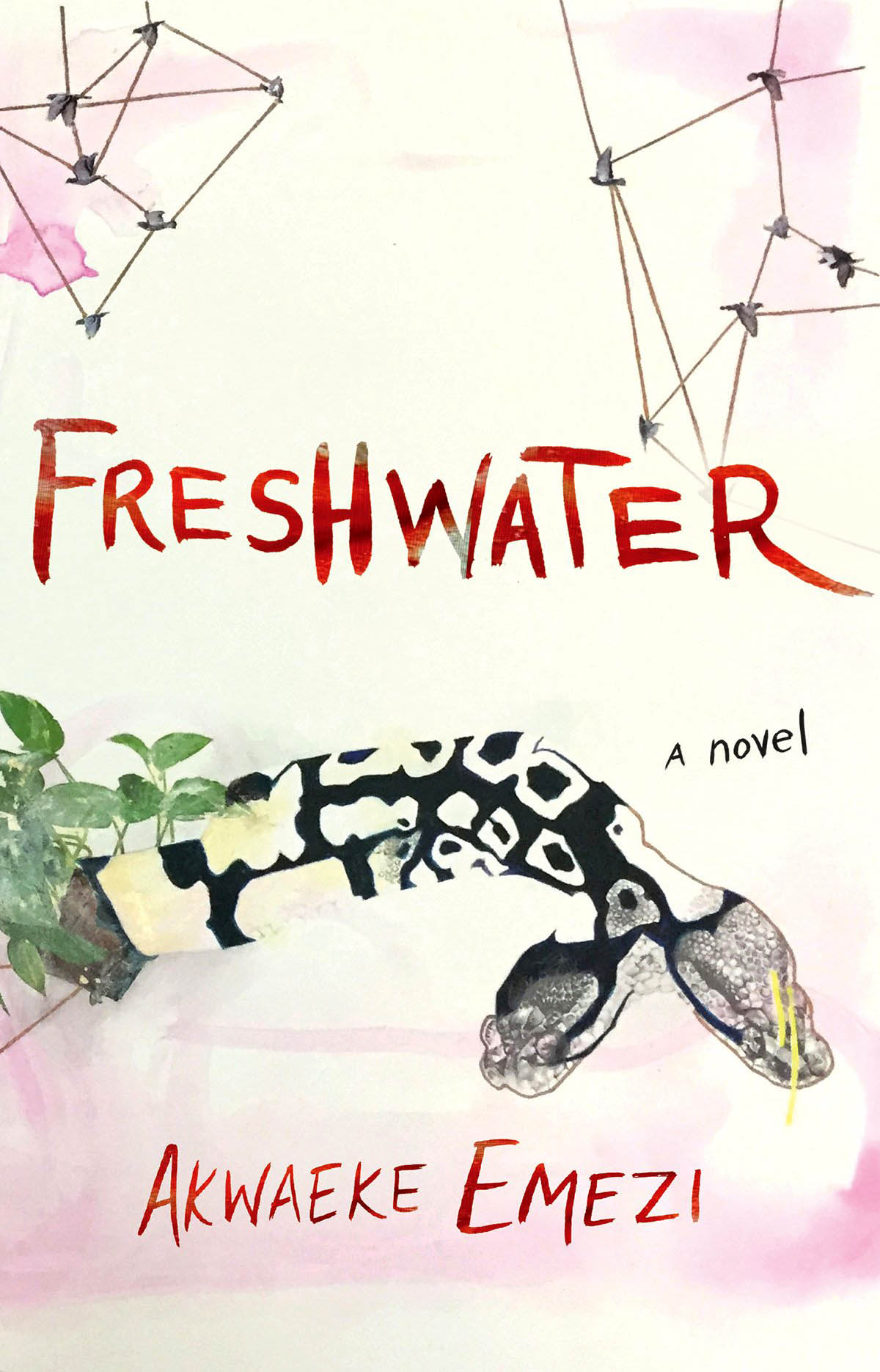

Imprinted in pages so deeply rich and intentionally frayed at the edges, Africa and her diaspora have always shared a deep give-and-take across the waters. A sense of displacement and becoming whole is found in the debut novel by Akwaeke Emezi titled Freshwater.

When Freshwater was published at the beginning of this year, I pledged myself a hardcover copy because the cover artwork was by ruby onyinyechi amanze. Both the author and the artist have Igbo roots, and the reconstruction of liminal spaces feels like distant cousins uniting to discover that their superpowers harmonise. The two-headed snake curling around the book spine through watermelon pink smoothly captures the hopping between the spirit world and the flesh world. I wonder if the fictional character Ada, who exists in the multimedia and ethereal drawings of Amanaze, shares a relation with the Ada of Emezi’s story, which unearths hybridity in terms of genre and imaginative configurations.

A story told through the voices of Ada’s multiple selves, Emezi shifts between the use of “let me tell you” and “let us tell you”, speaking on behalf of one and many. Reminiscent of folklore and a patterned stream of consciousness, Freshwater reminds you to speak back to yourself. You will be gently (sometimes a little to tightly) reminded of past experiences and self-made memories in the coiling embrace of time. It’s like singing along to Big Big World by Swedish singer Emilia in 1998, when MTV was the place to hear new music.

Emezi reminds their readers to feed their gods, and involves us in a practice of narratively experiencing and telling our worlds. But fragmented your worlds may be, whether you document them with words or just let the thoughts run away, the Afro-modern is taking up space in your territories and on your tablets.

Take Efemia Chela, for instance, a Ghanaian-Zambian writer whose story Sailing with the Agronauts is also published in As You Like It. From the opening line your wig will be snatched: “Christmas is my straightest time of year …”. Welcomed with resounding laughter at her reading at the Open Book Festival, Chela allows us to gain an external perspective on our ways of knowing with low-key charm. It is the kind of story that requires tea refills and may provoke some interesting conversation about queerness this December when you flock home, leaving a part of yourself in another city.

Africa’s emerging literary voices are full of pluralities, reflecting what this generation performs and undertakes.

And never forget that beneath the emerging mountain is a relentless force allowing us to begin again and open up emancipatory futures through the written word.