"Riding with Death" (1988). Acrylic and oilstick on canvas. 248.9 × 289.5 cm. Private collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Picture: Private collection, all rights reserved.

A painting can “not simply be reduced to what only a formal examination of its evidentiary summary allows”, writes curator and art critic Okwui Enwezor in the exhibition catalogue to Basquiat, a retrospective of 120 masterpieces showing at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris alongside an exhibition of Egon Schiele’s work, another major force in 20th-century art.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work was concerned with issues of “race, identity, masculinity and social agency”, adds Enwezor. The artist’s sister, Lisane Basquiat, interviewed in the latest documentary on him ( Basquiat: Rage to Riches, 2017) says: “If you want to know about Jean-Michel, look at his work.”

Several retrospectives since 1992 firmly stamped the artist’s reputation as one of the giants of contemporary art. Although one of his first sales in the early 1980s was a painting sold to the musician Blondie for $200, the May 2017 Sotheby’s New York auction sold Basquiat’s Untitled (1982) from his Heads series for $110.5-million.

Dos Cabezas (1982). Acrylic and oilstick on canvas mounted on wood supports. 152.4 × 152.4 cm. Private collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Picture: © Robert McKeever.

Yet the artist, born to Haitian and Puerto Rican parents, was rejected by most American art museums while he was alive. Inscribed into the Western art canon — in part, for reviving figurative painting in innovative ways — Basquiat is a hero to artists such as Banksy, who paid an unauthorised tribute to him on the exterior walls of London’s Barbican Centre in 2017 just prior to the retrospective there, Basquiat: Boom for Real. The American is often cited as the first black contemporary artist who made it big time. Today we are seeing an unprecedented interest in contemporary art by African-American and African artists, thanks somewhat to his uprising about 35 years ago. He died in 1988 at the age of 27.

Initially using downtown New York’s derelict buildings and subways as his canvas, together with Al Diaz (under the collective name “SAMO ©”, abbreviated from the local expression “Same Old”), he quickly went solo. “When he was asked why he wrote in the subway, he replied that it was in order to become famous,” curator and lecturer Simon Njami wrote in a 1992 edition of the African contemporary art magazine Revue Noire. “And, in effect, ‘SAMO’ succeeded in hoisting himself to the very top of the New York underground milieu, before propelling himself on to the walls of the best galleries.”

Walking through the Fondation Louis Vuitton exhibition I was struck by the rawness of Basquiat’s work; its confidence and spontaneity; the impulsive and uneven text — marking, erasing, scratching; the collaging, roughly cut and pasted; the frenetic yet controlled brushstrokes contrasted against areas of flat plastered colour and blank unprimed surfaces; the striking contrasting colours direct from the tube. The artist’s works invite a simultaneous viewing of the picture plane, which evokes his inner turmoil and angst and strikes you like a bolt of lightning.

Text is an equally important formal and considered tool. As curator Klaus Kertess reminds us: “He liked to say he used words like brushstrokes.” Not only words loaded with meaning, but words as forms and shapes. The artist also employed text as an encrypted vernacular.

Compulsively drawing and painting on any surface he could find, Basquiat’s unconventional mode was expressed on doors and panels of varying lengths and shapes, often assembled together as a narrative in exciting new formats.

In these examples the edges of the wooden frames jut out in all directions in asymmetrical lengths, breaking the conventional rectangular canvas mould with unpredictable freshness, as seen in J’s Milagro (1985), Untitled (1985) and Portrait of the Artist as a Young Derelict (1982).

“When [art dealer and curator] Jeffrey Deitch visited Basquiat in 1980, he described how the first thing [he] saw was a battered refrigerator that Basquiat had completely covered with drawings, words and symbols, the lines practically etched into the enamel,” recalls Dieter Buchhart, curator of Basquiat. “It was one of the most astounding art objects [Deitch] had ever seen.”

Basquiat poured his frenetic, sharp and raging mind on to the canvas as though there was a seamless connection between his uncensored thoughts and the paintbrush and crayon. The online photos and videos of him working give a sense of this. He depicted the grittiness of New York’s downtown graffiti scene of the 1970s and 1980s — an era of derelict buildings, piled-up garbage, drugs, racism and HIV.

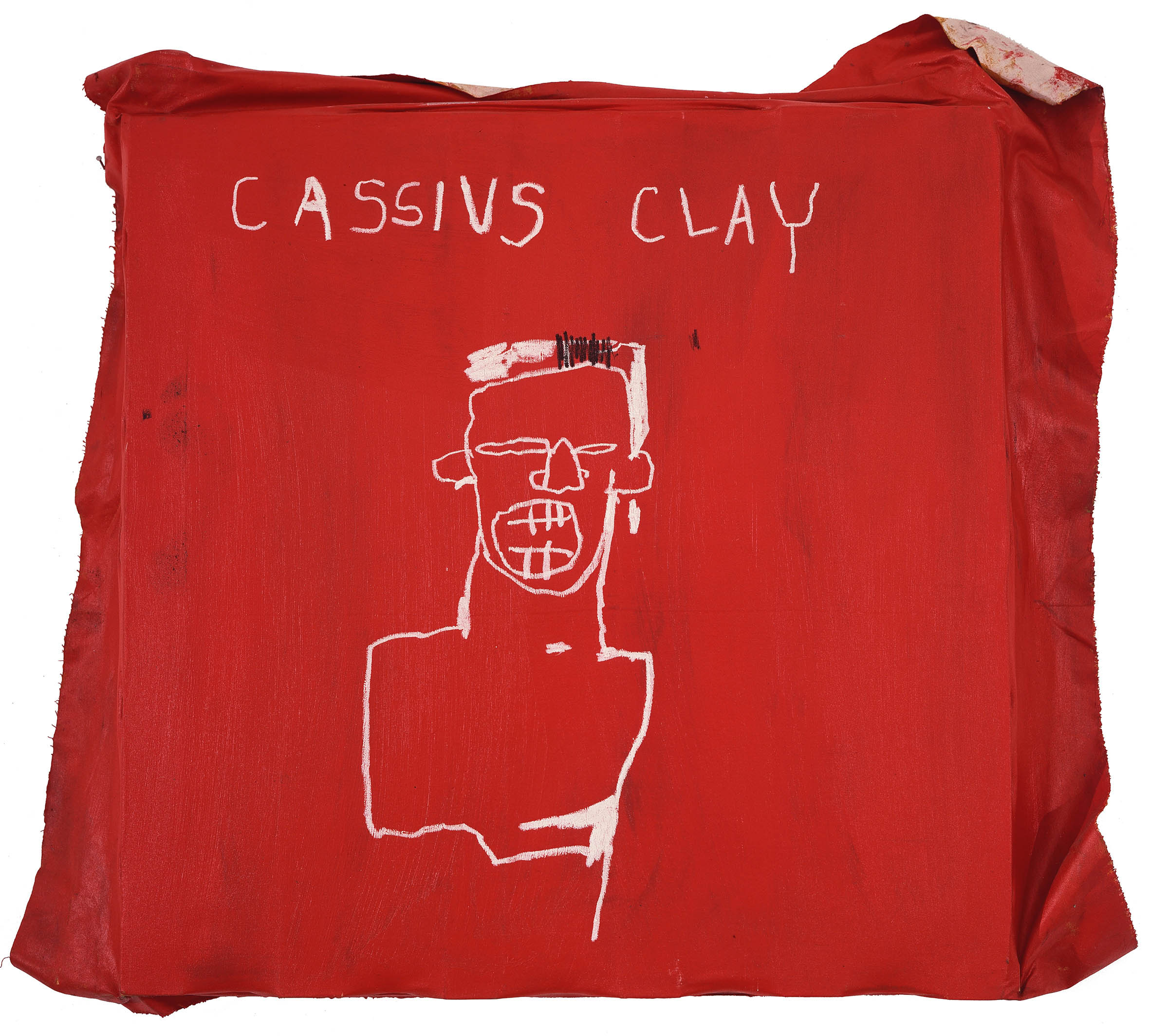

Self-taught, Basquiat looked to a long list of Western modern and contemporary artists for formal guidance: Cy Twombly, Robert Rauschenberg, Jean Dubuffet, Willem de Kooning, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and the Fauvists. He quoted from ancient Greek and Roman sources, but simultaneously inscribed into the art world’s glossary heroic, black masculine figures such as boxing legends Muhammad Ali and Joe Louis, revolutionaries such as Haitian Toussaint Louverture and musicians such as Nat King Cole. This recalled for me the 1950s era in South Africa, when black communities looked to the 1920s Harlem renaissance figures for sources of inspiration encouraged by the likes of Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald in music, Joe Louis and Jesse Owen in sport, and Langston Hughes in literature.

“Black people are never portrayed realistically … not even portrayed in modern art enough, and I’m glad that I do that. I use the ‘black’ as protagonist because I am black,” Basquiat says in Basquiat: Rage to Riches.

The artist inserted variegated vernacular African references, drawing on Nigerian and Kongo figurines (Exu, 1988) and the West African griots — musician storytellers and oral historians — (Grillo, 1984). Constant references to the Atlantic slave history emerge (Slave Auction, 1982) in broader concerns about colonisation, exploitation and racial discrimination in the Americas and the Caribbean. The artist’s works are a chronicle of black history and identity, from ancient Africa to the streets of 1980s New York.

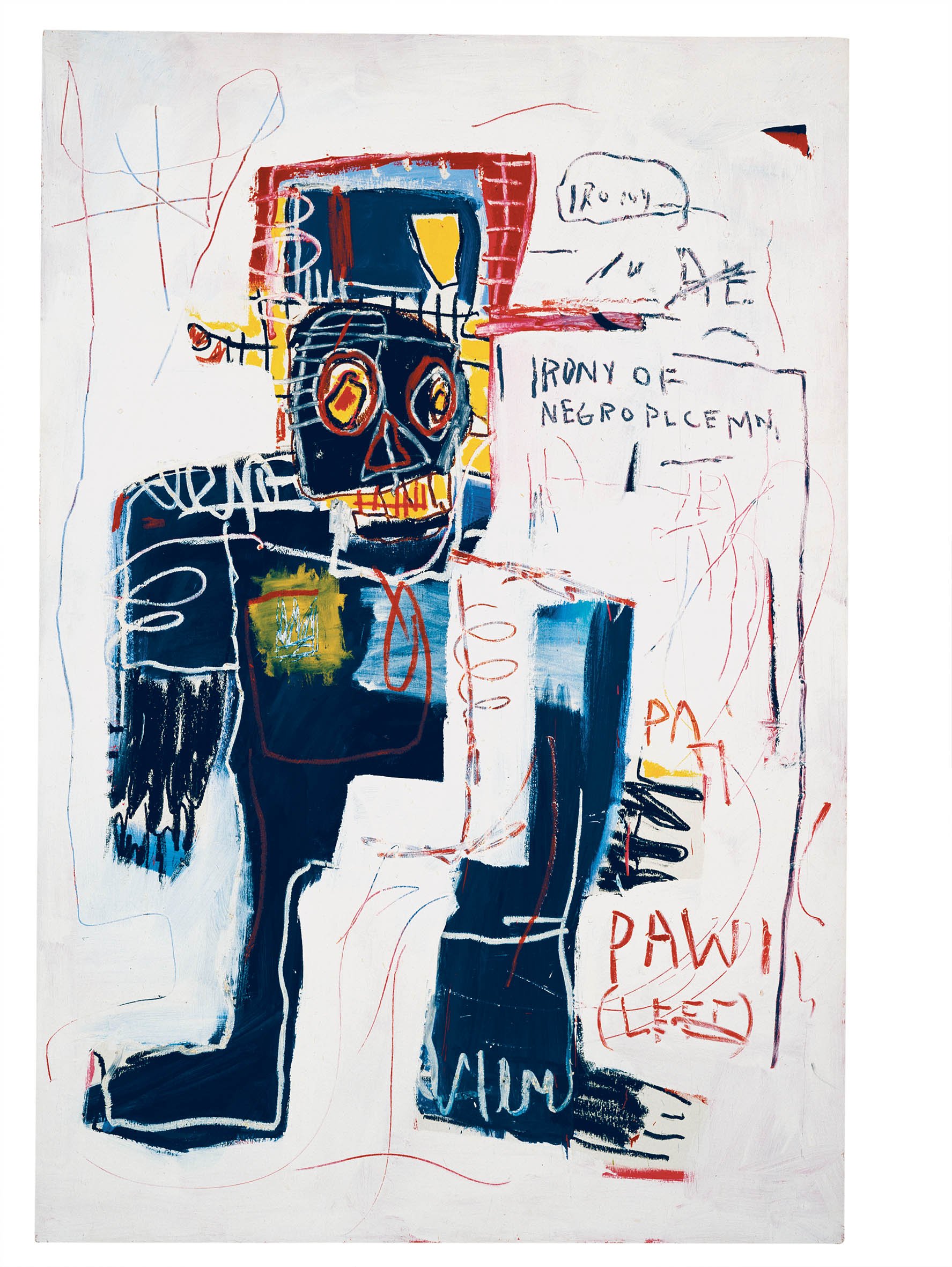

He was part of that world, of black graffiti artists who feared being arrested and beaten by the city’s police officers. His Untitled (Sheriff, 1981) reflects his trepidation about and suspicion of New York’s police force of that era and in Irony of Negro Policeman (1981) he grapples with the dilemma of how a black policeman could oppress other black people.

Creative canvases: Irony of a Negro Policeman (1981). Acrylic, oilstick and spray paint on wood. 183 x 122 cm. AMA Collection © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Picture: Courtesy of AMA Collection.

“In his work, colonisation of the black body and mind is marked by the anguish of abandonment, estrangement, dismemberment and death … The images are nakedly violent,” author and activist bell hooks wrote in 1993. “They speak of being torn apart, ravished … the black body as Basquiat shows it is incomplete. This image is ugly and grotesque. That is exactly how it should be. For what Basquiat unmasks is the ugliness of those traditions. He takes the Eurocentric valuation of the great and beautiful and demands that we acknowledge the brutal reality it masks.”

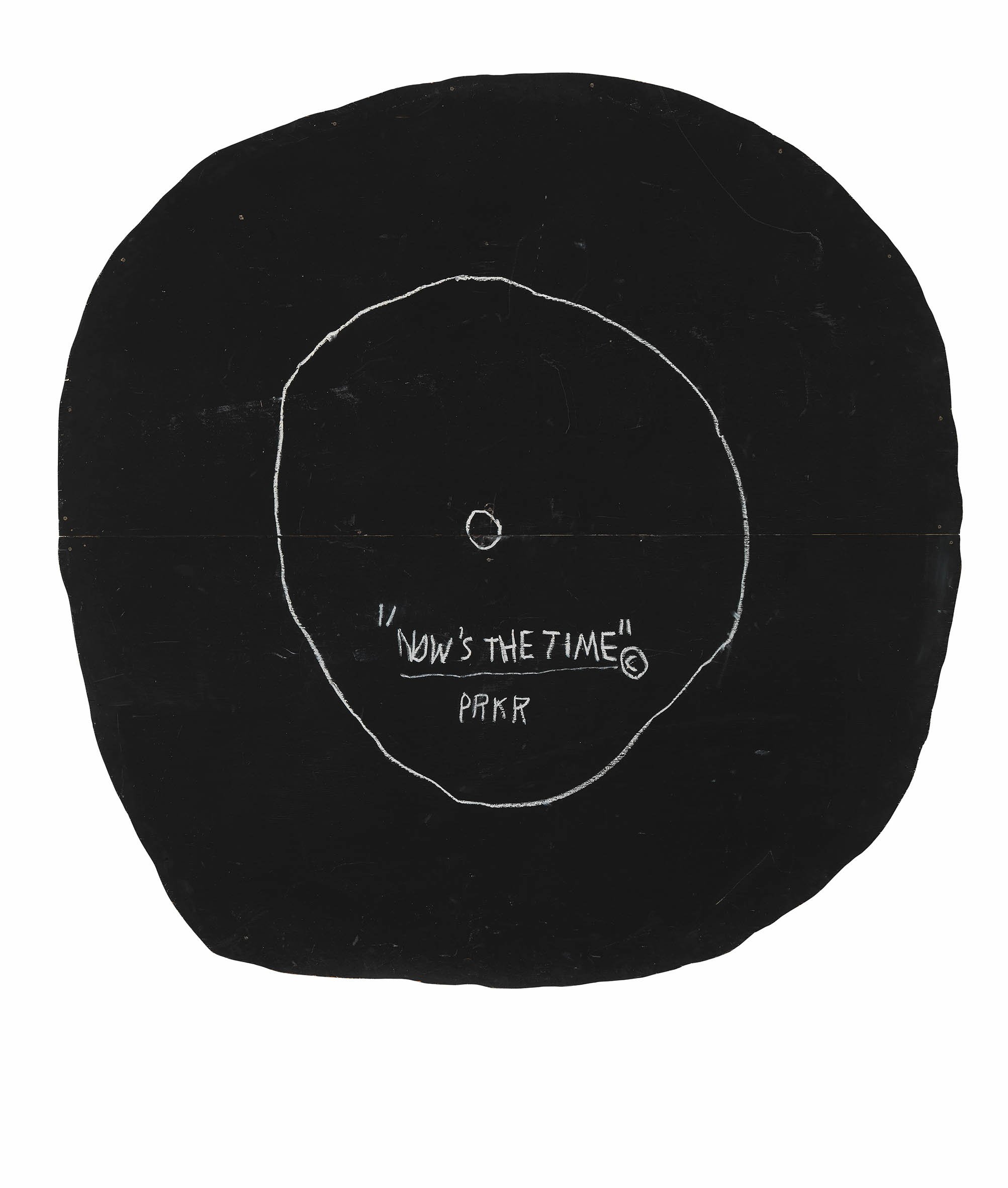

Basquiat’s highly prized art appears to be his early confrontational works, such as those from the Heads series, whereas his quieter works seem to be given less attention. One work that stands out for its simplicity, tranquillity and boldness pays homage to jazz musician and composer Charlie Parker. Now’s the Time (1985) reveals Basquiat’s love of jazz and bebop, which he drew on for inspiration. Buchhart remarks: “After painting the wooden disc black, Basquiat drew two concentric circles in white oilstick. He notes the composition title with a copyright mark and the toneless abbreviation of the musician’s name PRKR on the record. In so doing, the letters and squeezed-out words remain the subject of the painting.”

Now’s the Time (1985). Oilstick and acrylic on plywood, diameter 235 cm. Courtesy the Brant Foundation, Greenwich, Connecticut, United States. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York. Picture: © Robert McKeever.

The artwork in the Fondation Louis Vuitton exhibition lies between two-dimensional painting and three-dimensional sculpture. The found plywood, resembling an oversized vinyl, recalls the uniqueness of the artist’s drawings. SAMO ©’s improvised way of working could be compared with free jazz, spontaneously moving between drawing and painting, collage and text. Basquiat was no stranger to lyrics and music, having been involved with the band Gray and recording and producing an album titled Beat Bop under his own Tartown label.

Through this circular jazz artwork we catch a glimpse of a more conceptual direction Basquiat was exploring. It recalls earlier works such as Cassius Clay (1982), a portrait outline figure drawn in white acrylic against a flat, blood-red canvas, with the rough outer edges of the canvas visible to the viewer. Untitled (1982), of boxer Sugar Ray Robinson, is depicted in the same manner, albeit in white crayon on a black background.

Cassius Clay (1982). Acrylic on canvas. 106 x 104 cm. Bischofberger Collection, Männedorf-Zurich. © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Two of the artist’s most powerful paintings are very still works. One of his first works on canvas is Car Crash (1980). The canvas, which is not stretched and instead hangs freely from a wooden support, narrates a decisive moment in his life. The car accident was to be a life-defining moment, a passport, to expressive colours, marks uncontained and found objects transformed. In economical line, Riding with Death (1988) is a masterpiece — recalling the iconography of Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt van Rijn — of simple, calm brushstrokes on a smoothly painted canvas reflecting an acceptance of the coming death.

These two bookends of the artist’s career illustrate his remarkable development from young street artist with a compulsive artistic expression into one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

Although the Fondation Louis Vuitton exhibition is pristinely curated, with many of Basquiat’s major works on display and a fine catalogue with several interesting texts from different perspectives, the context (historical, visual and sonic) would have enriched the experience. The complex and intense colour-laden works that brilliantly scream out against the museum’s white walls appear to be exclusively reduced to a formal examination of Basquiat’s work. The photos and other archival material hinted at in the catalogue — such as the exhibition poster advertising the face-off between Basquiat and Andy Warhol in boxing trunks — would have been a wonderful inclusion in the exhibition, adding texture to understanding not only the formal qualities in the artist’s legacy, but also those facets of the artist’s mythical narrative that are concealed.

Basquiat is shown alongside a retrospective of about 100 works by Egon Schiele, a leading figure in early 20th-century Expressionism. The Art Story notes that: “His portraits are searing explorations of sexuality and the psyche” and defied “conventional norms of beauty”. Similar to Basquait, Schiele died young, at the age of 28. Both shows are curated by Buchhart and invite comparisons between the two masters, born 90 years apart. “The works of these two extraordinary artists are characterised by their extreme intensity, energy and productivity,” said Buchhart, adding that both “reflected in their drawing practices their aggressive and expressive distortions of the body”.