Robots weld a vehicle at a Ford plant in Cologne. Seven motor vehicle companies in South Africa have invested in state-of-the-art production facilities. (Oliver Berg/dpa)

If you go through the 2018 budget, you will find that the category that costs the fiscus most in terms of tax forgone is zero rating on foods. This amounts to about R55-billion.

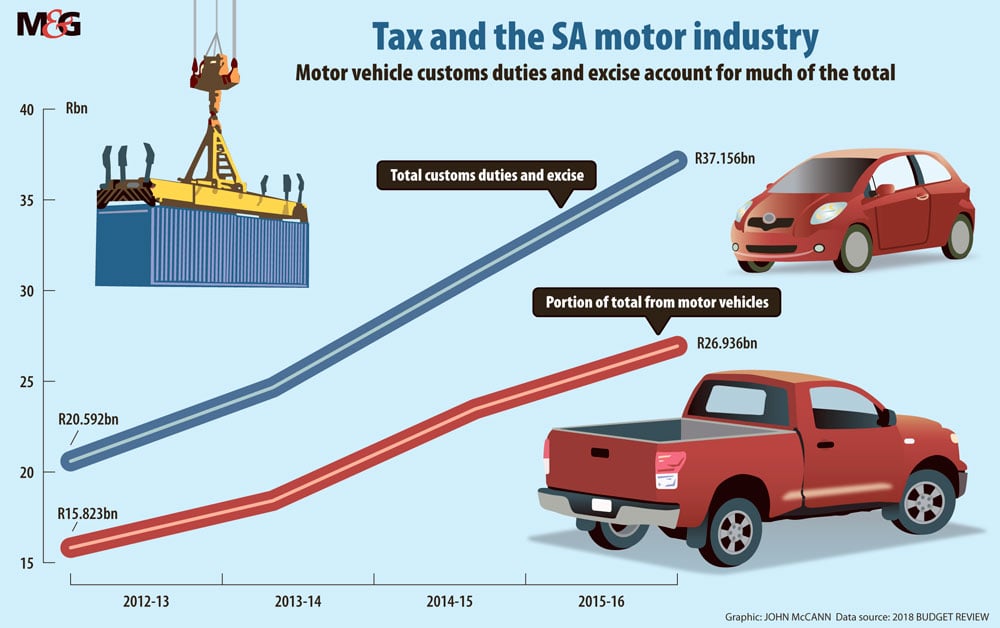

This is followed by tax exemptions on pensions — R31-billion. But not far behind is the R27-billion that goes to the motor industry. This has increased by almost 50% in the four years between 2012 (about R15.8-billion) and 2016 (R26.9-billion).

According to the 2018 budget, the increase “stemmed from higher customs and excise expenditures, largely the result of strong growth in expenditures” that were related to South Africa’s motor programme. The Motor Industry Development Programme, which was replaced by the Automotive Production Development Programme (APDP) in 2012, will run until 2020, when it will be replaced by the South African Automotive Masterplan (SAAM), which is intended to be in effect until 2035.

Incentives paid to corporate investors have both supporters and critics. Supporters say the industry contributes 6.9% to South Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP), supports 112 000 jobs and creates state-of-the-art production facilities. By the end of 2017, the seven motor vehicle companies in South Africa had invested more than R32-billion in production facilities over five years.

The automotive sector accounts for 50% of all vehicles sold on the continent. But, despite generous support from treasury, the industry, which produces about 600 000 vehicles annually, has so far undershot its intended APDP target of one million vehicles by 2020.

Sales in the economically sluggish economy have also been poor. In 2018 552 190 vehicles were sold locally, a decline from the 2017 figure of 557 703. The decline, according to the National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa (Naamsa), was attributed to “a weak macroeconomic environment, pressure on consumers’ disposable income and fragile business and consumer confidence”.

But critics say the incentives could amount to corporate welfare, and Tax Justice Network chief executive Alex Cobham has urged that the industries that benefit from tax forgone by the government should be reviewed regularly to maintain transparency.

“This corporate welfare undermines fair competition, distorting markets so that consumers as well as taxpayers are hurt. But, on top of this, the tax incentives are often opaque to citizens and enacted without parliamentary scrutiny, making large-scale corruption possible and even likely,” he said.

In a 2016 World Bank study, which analysed South Africa’s tax incentives, found that, between 2006 and 2012, they resulted in 34 000 additional jobs overall and additional investment of R2.1-billion but revenue forgone amounted to R4.5-billion, or R116 000 a job.

The implementation of the SAAM is intended to avoid the end of South Africa’s automotive industry, as happened in Australia when its last car manufacturers (General Motors’ Holden, Toyota and Ford) closed in 2017.

This was the result of several factors, but mainly the Australian car market being flooded by cheaper imports and the country’s distance from its export markets.

Australia’s minimum wage (US$1 1 dollars a day) also made it difficult to compete with neighbouring countries (such as Thailand, where the minimum wage is US$9.70 a day) to export vehicles competitively to international markets.

For the past 10 years leading up to 2017, the Australian automotive industry relied on government support to stay afloat, and taxpayers paid AUS$5-billion into the industry, according to motor publication Autocar.

Another case study of mooted corporate welfare is Nissan’s production line in Sunderland in the United Kingdom. Employing more than 7 000 people, Nissan has produced vehicles in the northeast of England for almost 40 years, investing £3.7-billion into its UK operations. But researcher Kevin Farnsworth, who is the executive director of UK-based Corporate Welfare Watch, said this investment came at a price, because the UK promised to cover up to a third of Nissan’s initial capital costs in the 1980s and sold land to the motor company at a hefty discount.

By 1988, the UK had put £125-million into Nissan’s production facilities. That, because of various government loans and policies and corporate welfare, now amounts to £797-million.

Naamsa said in a statement that the duty rebate mechanism for the motor industry was intended initially to “force model rationalisation and encourage more efficient, longer production runs per model”.

The mechanism, under the APDP, benefits vehicle and component production “irrespective of whether such manufacturing was for the local or global markets” and it “allows offsetting of import duties through the local content of vehicles produced”, Naamsa director Nico Vermeulen said.

Econometrix economist Sam Rolland said, because South African producers could not manufacture everything locally, “they can offset some of the import costs by meeting production volumes. The rise of import rebates in the [2015-2016] period would either have been a result of an increase in production, or an increase in claims on rebates, or both.”

The treasury said in the 2018 budget that tax expenditures had to be reviewed periodically to prevent wasteful spending.

The department of trade and industry’s spokesperson, Sidwell Medupe, said the APDP had been largely successful because it ensured “South Africa still has an automotive industry, notwithstanding recent and current global and local economic conditions ranging from the 2009 financial crisis [that] retarded growth in the region to very low domestic economic growth”.

But, “in terms of achieving initial targets of producing more than a million vehicles a year, the APDP did not succeed”, he said.

In 2018, South Africa produced about 610 000 vehicles, an increase from the 601 178 vehicles produced in 2017. It is expected to produce 657 500 vehicles in 2019. It is the continent’s biggest vehicles (including trucks) producer.

Much of the original equipment manufacturer production took place in Pretoria, Durban and East London, Rolland said, which played a vital role in KwaZulu-Natal’s and the Eastern Cape’s economies because “these provinces are not as diverse as Gauteng’s economy”.

He said, compared with our own market, the export market played a large role in South Africa’s production and, although South Africa wanted to be the springboard to export into Africa, there was already competition, because Kenya and Nigeria assembled semi-knocked-down vehicles and Morocco’s motor industry is growing.

Vehicle production in Morocco increased nine times between 2010 and 2017, according to Naamsa president Andrew Kirby.

In 2017, according to the 2018 Automotive Export Manual, Morocco produced 341 802 passenger vehicles, surpassing South Africa’s 331 311 units.

Although South Africa had better ports, more skills and greater political stability, Rolland said: “We are also far from our markets.” South Africa exports the majority of its vehicles to Europe.

The SAAM aims to make South Africa’s automotive industry globally competitive, as have previous automotive plans, but to keep it sustainable it has to export more than 350 000 vehicles to 149 countries. According to the 2018 budget, the APDP will be reviewed to assess its success and to decide on how it should be amended. The report on the APDP is expected this year, according to Southern Africa’s non-manufacturing group Motus.

The SAAM, largely seen as an extension of the APDP, will take over from 2021 to 2035. Its intention is to increase the number of people working in the automotive industry to 224 000 (from 112 000) and double the percentage of vehicles assembled in South Africa from 38.7% to 60%. This will amount to 1.4-million vehicles produced annually.

It also plans to transform the automotive supply chain by achieving broad-based black economic empowerment status four.

The SAAM has been welcomed by the industry, and Saul Levin chief executive of not-for-profit economic research organisation Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies, has said: “The continuation of the APDP, and its tweaking so as to strengthen and build the automotive supply chain domestically, will continue to increase the capacity of the main firms and will further support industrialisation and job creation in South Africa.

“Not only does the automotive sector bring direct jobs, it also comes with a number of other benefits, such as technological capacity,

skills development, exports and import replacement, amongst other things.”