An ode to Trevor Makhoba's 'Studio Visit' (2001) 'Jy moet jou ma da by die wit mense vir nou enjoy want aan die einde kô amal huis toe' The artists mother on the topic of mixing races (2002) by Lady Skollie (Paulo Menezes)

Co-curating, as well as participating in an arts writing workshop running parallel to the exhibition, Sumayya Menezes reflects on trawling through the source material that birthed Mating Birds Vol.2

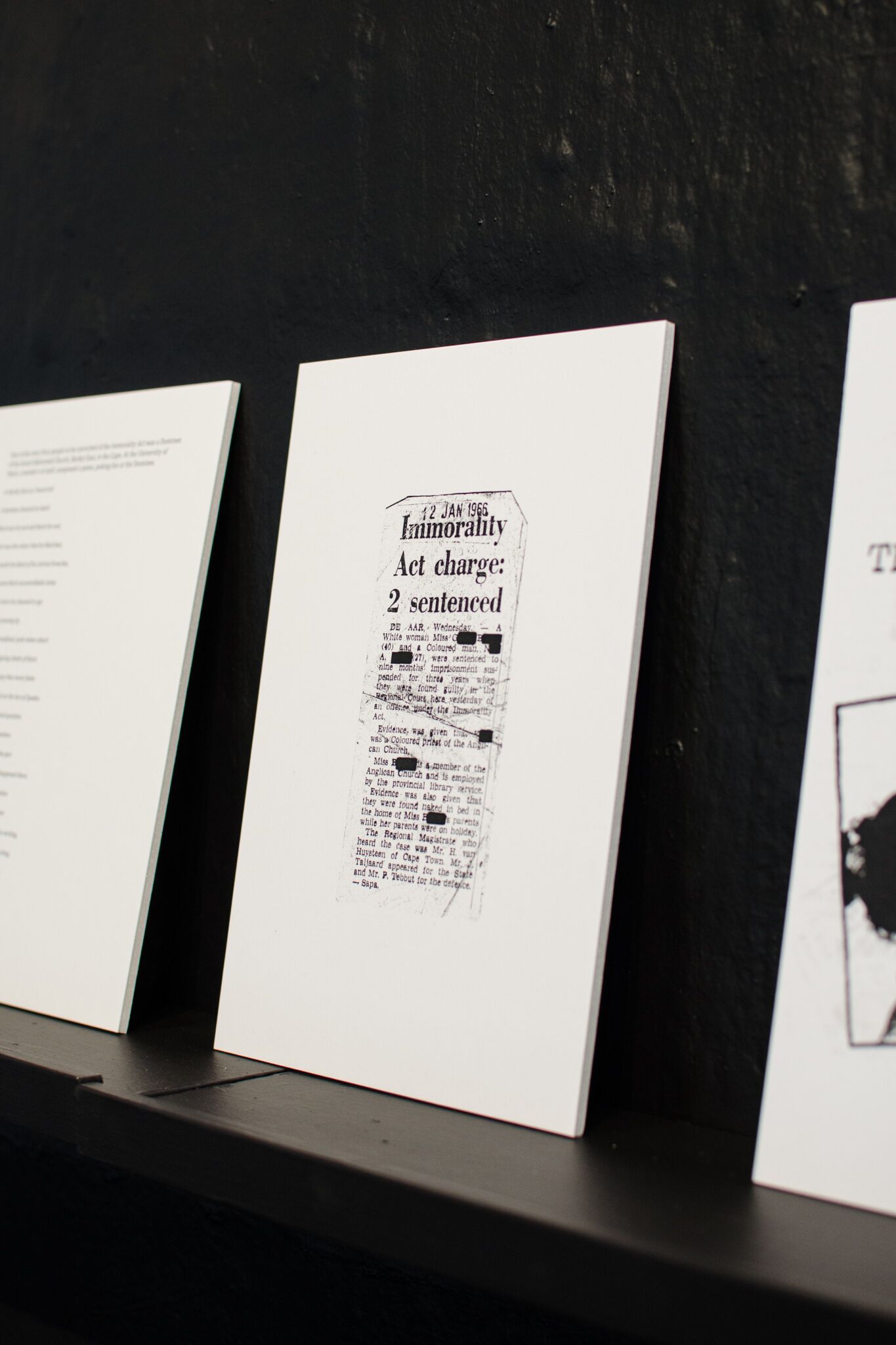

Mating Birds Vol.2 draws on a host of sources including original artwork, reference material from art, literature, philosophy, legal documents, letters, newspaper clippings and exhibition catalogues.

(Paulo Menezes)

(Paulo Menezes)

For me — a somewhat green, fledgling curator navigating the concept of a curatorial essay under the wing of Gabi Ngcobo, the scale of the research this entailed was extraordinary. Artists and artworks, fiction and nonfiction, archival documents complete with Afrikaans footnotes — the range was extensive and left nothing out. Three short months later, the research has come together and Mating Birds Vol.2 inhabits the exhibition space with a quiet sense of purpose, inviting visitors to delve into the historical narratives it begins to unpack.

The facts are presented in impartial black and white, with three versions of the Immorality Act and its amendments (Act No.5 of 1927, Act No. 21 of 1950 and Act No.72 of 1985) displayed officiously behind glass. A few photographs of segregated beaches illustrate them — some obscenely brightly coloured, the bluest of skies and sparkling waters impossibly at odds with the ugly histories contained within the frame.

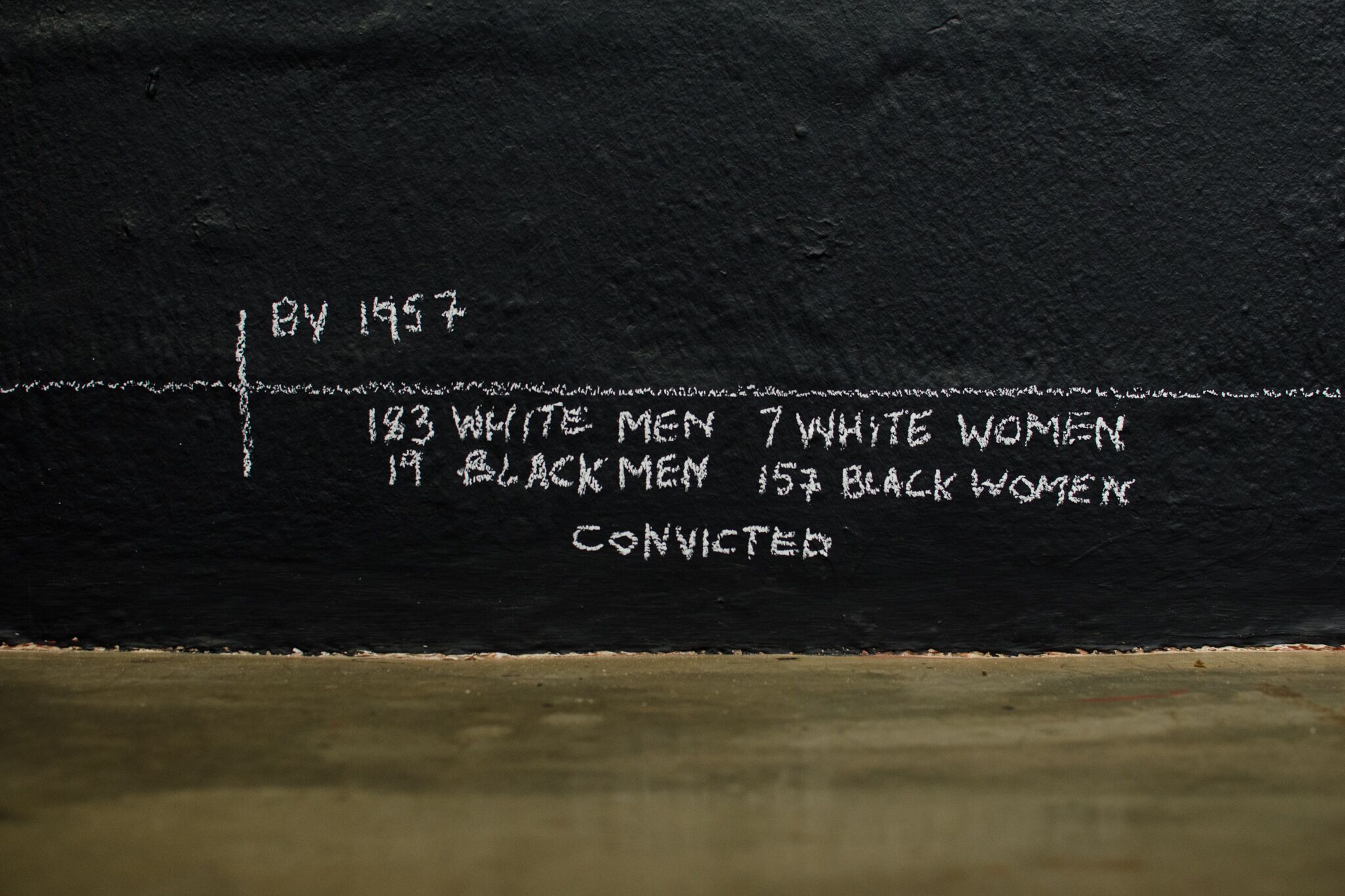

Beyond, a timeline stretches across the wall. White chalk on a black wall, acts and several amendments march through the decades, punctuated with statistics. ‘From 1950 to 1961, 4379 persons were convicted under the act’, ‘1962 – 1967 3871 arrested, 2055 convicted’ the chalk intones. Moving upstairs, it continues relentlessly: ‘In order to trap suspects, police have resorted to climbing trees, hiding in the boots of cars, feeling beds for warmth, peeping through keyholes and windows. Non-white women have also often been used as traps.’ Throughout the space, Simnikiwe Buhlungu’s silkscreen banners are insistent, unavoidable — ‘We are not making this up!’

(Paulo Menezes)

(Paulo Menezes)

Yet, interspersed between these cold pronouncements, there are distinct slices of brave humanity. Floating serenely in a wall-mounted box, Zanele Muholi lies elegantly draped with her lover; Caitlin and I is a scene of trust and surrender, a portrayal of two bodies at rest and at peace with each other, and the world beyond the lens. The accompanying text from Zethu Matebeni’s Intimacy, Queerness, Race confirms their repose and continues, ‘With their gaze, they are breaking down the gaze of the viewer, undoing conventional ways of viewing’.

Above the women, a prison stamp draws the eye to a series of letters, extracted from Til the Time of Trial: The Prison Letters of Simon Nkoli. Discovering these letters while researching for the essay, I was struck by the unquenchable humanness of Simon Nkoli, penning letter after letter to his lover, Roy Shepherd, while incarcerated for four years awaiting trial for treason.

Lovemefuckme by Tracey Rose (Paulo Menezes)

Lovemefuckme by Tracey Rose (Paulo Menezes)

‘My dearest Roy’, begins one dated May 31 1986 ‘… Brown suit! Mm, that is what I asked you to buy for me. Brown suit will be nice with a yellow or pink shirt and brownish tie.’ Here was a man whose spirits were raised at the prospect of a fashionable new suit. The letter continues, softer now, more vulnerable and pleading — the voice of a man concerned for his beloved’s safety. ‘Roy I am happy that you are not going in the townships. It is not safe at all – so please as long as I am in Prison, honey keep yourself away from the townships, even if one of your black friends invited you, Roy. For my sake honey stay away …’

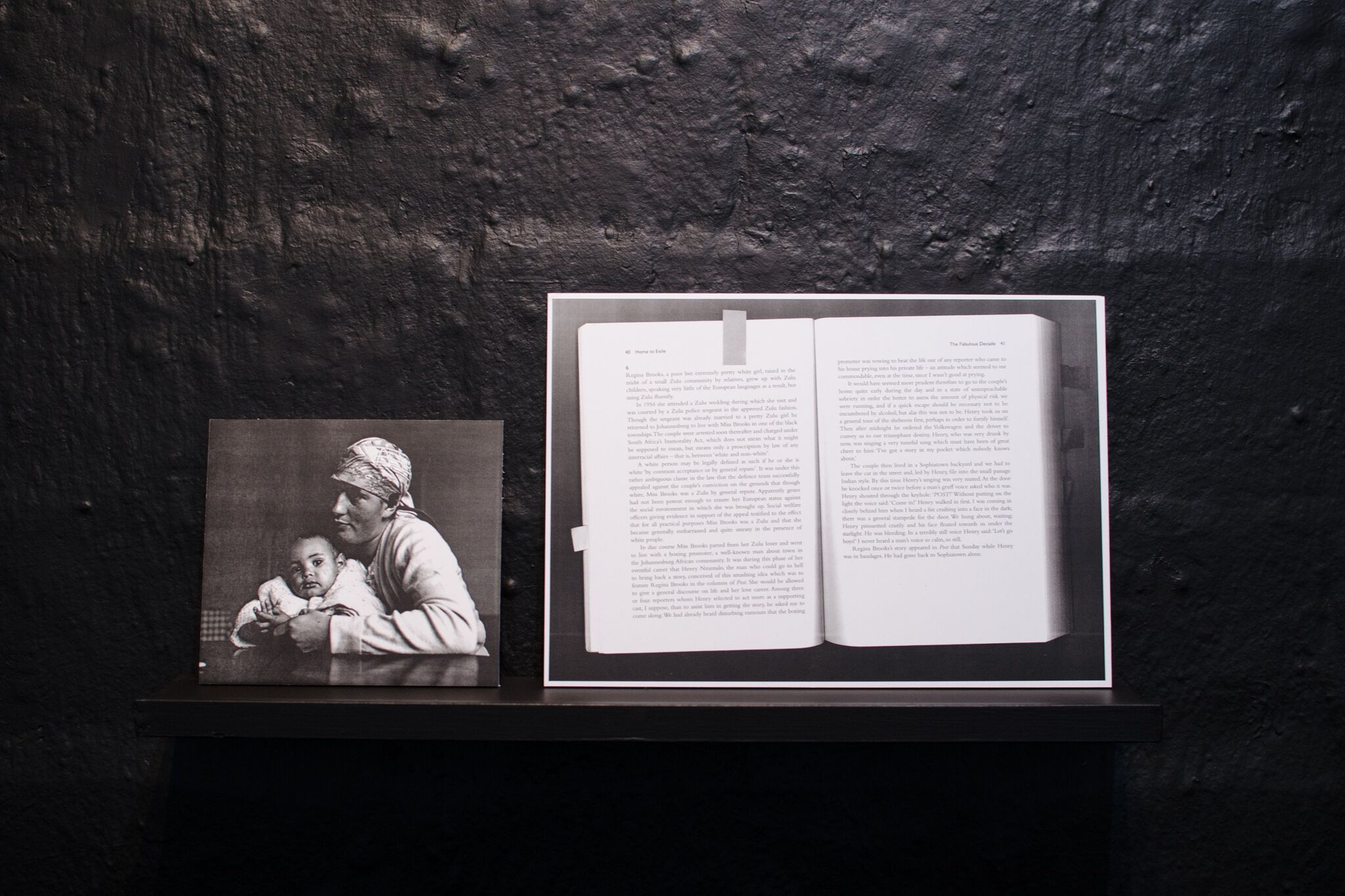

Here was the story of a man, separated from the one he loves. Race or gender were suddenly irrelevant; pain and heartache make no such distinctions. Across the mezzanine, another story beckons. Newspaper clippings hold the image of Regina Brooks, a white-skinned woman charged under the Immorality Act in the 1950s. Brooks, who grew up learning Sotho and Zulu from her father’s farm workers, dated a black police officer, Sergeant Richard Khumalo, when she was 18 years old. After a long trial, she emerged victorious when the courts ruled that she was not white as she ‘spoke Zulu fluently, wore a doek and put her child on her back like all black women’. Brooks was later re-classified as ‘other coloured’ and in 2017, her story was brought to life in a play, Gone Native: The Life and Times of Regina Brooks presented by the Soweto Theatre.

Regina Brooks (Paulo Menezes)

Regina Brooks (Paulo Menezes)

Another stage comes to mind and I recall Trevor Noah, South Africa’s much loved comedic export and famously ‘born a crime’. His is a narrative not directly referenced within the exhibition space but encountered in our research and familiar to many. Born to a white Swiss father and a black Xhosa mother in 1984, Noah’s autobiography is prefaced with the text of the Immorality Act of 1927. It’s sobering to realise afresh that just a single generation lies between today and the final amendment of the act, Act No. 2 of 1988. Buhlungu’s banners nod, sagely — ‘This we are not making up!’

Slightly removed from the newspaper clippings and damning chalk, Billie Zangewa’s La Danse stands alone at the end of the gallery. A delicate, whimsical piece, the silk tapestry seems to transcend the weighty archives that share the space. A black woman in a red dress, dancing with a white man. ‘Une histoire d’amour’ it proclaims in uneven black letters – ‘A love story’. In the background, hand embroidered snippets of the pair’s conversation as they dance, and we understand that this is a recent acquaintance, still flush with newness and giggly flirtation. There is no sombre undertone of menace, no threat of authority peeping through keyholes or windows looking to make arrests. They are simply a couple, enjoying this dance and its possibilities, and we cannot hear the music.

Back downstairs, in the curatorial statement accompanying the essay, a line from Frantz Fanon (Black Skin, White Masks) introduces the text: “Today I believe in the possibility of love; that is why I endeavour to trace its imperfections, its perversion.” Paging through Mating Birds Vol.2 in the exhibition space, one is invited to pause and reflect on the perversion of love in the time of the Immorality Act and its many amendments, and the possibilities that, for some, never could flourish or bear fruit. A historical narrative saturated with facts, figures and statistics, easily traced through the archive — but with many gaps, waiting to be peopled with memory.