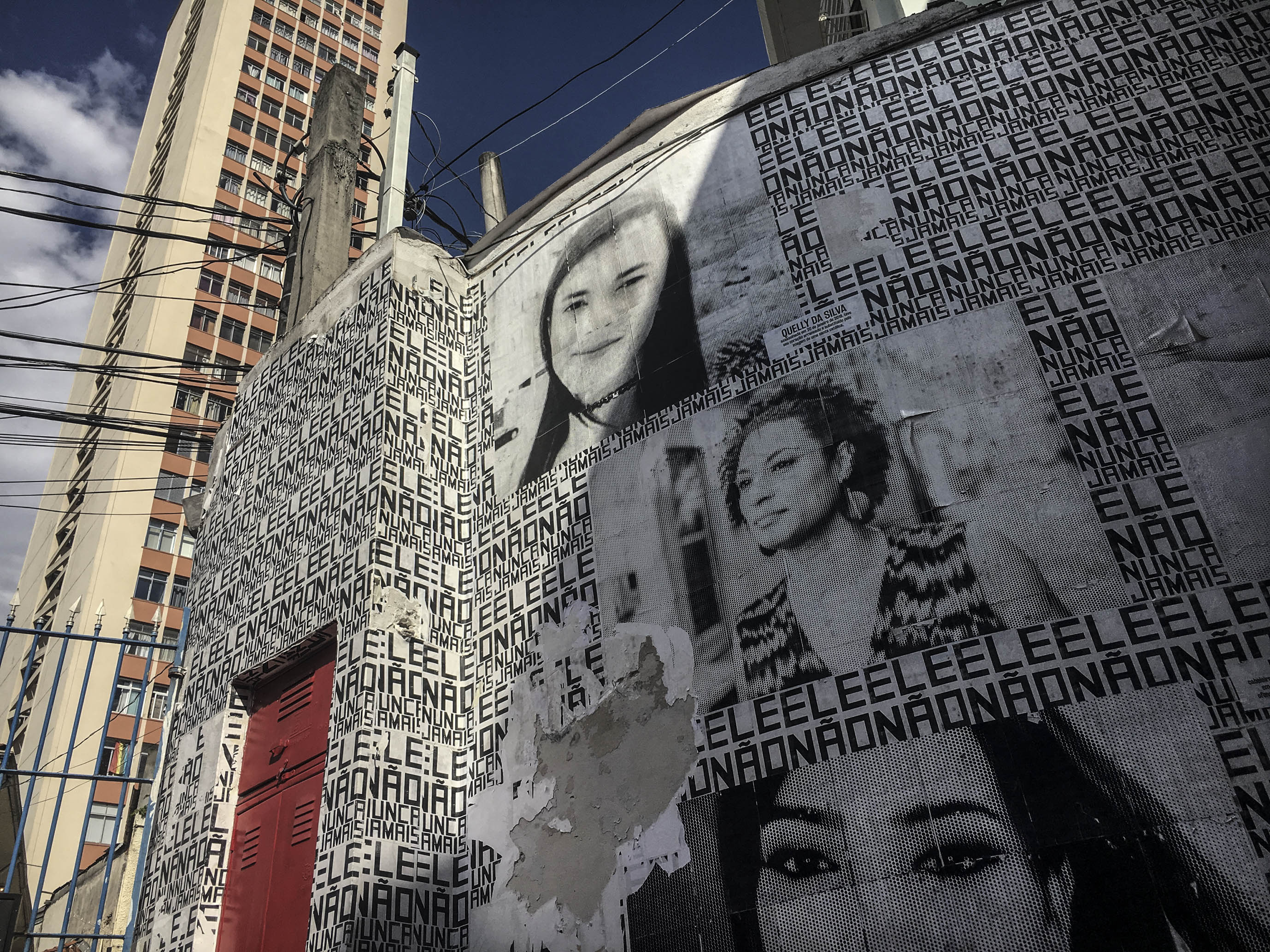

Not him: Brazilians demonstrate against right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro. Photo: Pablo Albarenga/ Getty Images

She introduces herself simply as Daniela as she stands outside the tiny shop on a busy central São Paulo street filled from floor to ceiling with second-hand clothes.

Daniela is a transgender woman who runs a shop at the shelter that gives away clothing. Photo: Carl Collison

The word “shop” is not quite right, though. It is a place where the area’s homeless get clothes for free. This service is run by the people who established Casa 1 (Home One), the country’s only shelter for homeless lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) people located upstairs.

It’s opening time and Daniela pulls up the metal roller-gate. On it the names of people who have been victims of queer-phobic violence are written in remembrance. “Unidentified trans woman shot to death — 6 March”, “Joaquin — stabbed to death”, and so on.

The Casa 1 shelter wall is plastered with images of queer people who were murdered. Photo: Carl Collison

Brazil has one of the world’s highest rates of LGBTQ murders. In 2017, for example, 445 such murders were reported.

Dressed in tight-fitting black leggings and a sleeveless red blouse, Daniela — a transgender woman living in a society where 35 is the average life expectancy for trans women — is defiant. To hilarious effect, she loudly implores passers-by: “Look my body. Is very, very amazing, my body. Is very, very, very beautiful, my body. Delicious. My pussy. She’s beautiful. My ass. She’s amazing.”

Daniela is also showing off the fact that she has recently started English classes, something she hopes will increase her chances of gainful employment.

These are offered by Casa 1’s cultural centre, less than 10 minutes walk away. It also runs Spanish, Portuguese (for gringos, of course), sewing, embroidery, yoga and self-defence lessons to anyone, not just queer people.

Angelo Castro, one of the centre’s directors, says opening these courses to everyone gives people the opportunity to learn skills while also getting to know “what a trans person, a gay person, a lesbian person is. Because a class on sexual orientation and gender identity would not work. By offering these courses instead, the community is given the opportunity to be in contact with LGBTQ people. In that way, the community will have a greater understanding [of sexual orientation and gender identity] and be more accepting.”

Angelo Castro is one of the directors of Casa 1, a shelter for homeless queer people and a learning centre open to everyone so that straight and queer people can get to know one another. Photo: Carl Collison

The centre’s blue metal gate creaks open and shut with regularity as all manner of people — queer, straight, hip young things and those down-on their luck, bearded boys in heels, trans girls in jeans — enter and exit. All the while, neighourhood kids play football under the gaze of murdered queer people, whose large-scale printed faces are plastered on the centre’s walls.

Under their haunting, defiant, slowly fading black-and-white faces, the words “ele não” (not him) are repeatedly, boldly, printed to almost dizzying effect. The “him” referred to is the country’s recently elected president, Jair Bolsonaro.

A virulent homophobe (of the “I’d rather have my son die in a car accident than have him show up dating some guy” variety), the populist right-wing extremist’s ascent to power has hit the country’s marginalised groups particularly hard.

A 2019 report by Human Rights Watch noted: “Brazilian media reported about dozens of cases of threats and attacks against LGBT people during the presidential campaign, many of them allegedly by Bolsonaro supporters.”

Brazilian councillor Marielle Franco promoted the rights of black women and queer and young people and spoke out about police killings. She was assassinated in São Paulo in March last year. Photo: Miguel Schincariol/ AFP/ Getty Images

A pre-election article published in The Guardian by Brazilian journalist and documentary maker Eliane Brum states how the left views Bolsonaro’s ascension to power as “more frightening than any dystopian fiction”.

“During the first decade of this century,” Brum writes, “Brazil appeared to be a country that was finally reaching for the future. Now it seems mired in the past. The violence of this election has plunged Brazilians into a kind of collective convulsion. There is no other subject; people are starting to feel sick with fear.”

Castro says the centre has seen first-hand how, in the run-up to the elections, Bolsonaro supporters offered hints at this future dystopia.

“During elections, because we have this wall [with ‘not him’ written across it], cars would drive past and scream, ‘Bolsonaro!’, which is sending a very clear message. If someone shouts ‘Bolsonaro’ at you in that way, they are essentially saying they are against your existence.”

But, Castro says, the work being done at both the cultural centre and the shelter continued undeterred. “What we did when that happened was what we do every day: we keep working,” he shrugs, laughing. “That is how we manage it. Because we know that the community — the same people who do those kinds of things — will need our help at some point and would need to come here.”

By way of illustration, Castro tells a story. “Once, one of the children who uses this space did something bad and we told him that he won’t be allowed to visit the centre for a while. His parents came here to discuss it and the child was trying to convince his parents that he didn’t do this thing.

“At one point in the conversation, he says to his father, ‘But you dad, you yourself always tell me that this is a faggot house’. And then the dad says, ‘But if I didn’t trust them, I wouldn’t allow you to come here’. So in a certain way, people in the community don’t accept us being here 100%, but we still have their trust.”

Ivan Giusti is the founder of the “faggot house” and the shelter. An LGBTQ activist, Giusti says he got the idea to start the shelter after years of hosting people in his house through Airbnb.

“But I realised I didn’t really need that money, so I decided to open my house to the LGBTQ community,” he says. “Once I started doing this, I started seeing how big the need was for LGBTQ people to have a space like that where they could feel safe. As a cis-gendered white person, you don’t really realise how big this need is … until you see it.”

The shelter can accommodate 20 people and receives “about five requests a day” from young queer people needing a roof over their heads after being rejected by their families. “Ninety percent of people at the shelter are black,” he adds, attributing this to “a matter of privilege”.

“A white boy, for example, would usually have an established network around them. We are a reflection of the inequalities in this country. Being LGBTQ is only one of the issues they suffer when they are thrown out of their homes. There is poverty and blackness as well.”

Only a few days earlier, the founders had publicly announced that, because of a lack of funding, they could soon be forced to close their doors. The substantial source of their revenue stream — corporations — had dried up. Or rather, he says, “disappeared”.

The reason for this? Giusti laughs wryly: “Bolsonaro was elected. That is what happened. Since he was elected last year — around October, November — the companies that were giving us financial support all disappeared. It’s very different here from, say, Europe or the United States, where companies have this mind-set of helping out LGBTQ organisations. So it was a very new thing which was starting to happen. But then this happened … He was elected.”

Brazilians demonstrate against right-wing President Jair Bolsonaro. Photo: Pablo Albarenga/ Getty Images

But, says Giusti, Bolsonaro’s election also has him feeling “relieved”.

“Brazilians are very cordial. We act as though we are very open, but there is racism here. There is prejudice here. With Bolsonaro [coming into power], people are starting to act out their prejudices, whereas normally nobody would say anything. So now at least people are discussing things like racism more openly.”

Added relief has also comes from the fact that, within a few days of announcing the shelter and centre’s pending closure, they have raised more money from individual donations than they had in the two years since opening their doors.

“Over the past two years, we only managed to get R$22 000 monthly through donations from individuals. But over the past three days, we have secured close on R$60 000 [in monthly pledges],” he shrugs with grateful incredulity.

As to what he ascribes this to, Giusti says: “Culturally, Brazilians only do something about a situation when they are about to die or something. We have this saying, which basically goes: ‘When the water hits your ass is when you do something’.”

Although grateful for the water finally having hit people’s asses, the difficulties persist. “The money raised will be used to keep things the way they are running currently, which isn’t really ideal. We pay the staff about R$800 [a month], but they work 12 hours a day, seven days a week. So we really want to pay them more, you see? That’s the only way we can keep the house and centre going and continue helping people in our communities. People like Daniela.”

Heading to the subway, my interpreter and I walk past her and the little shop she manages. Demurely sitting on a makeshift chair, she looks up from her phone and waves us goodbye with a loud “congratulations”.

Laughing good-humouredly at her broken English, we walk away knowing she can still continue those English classes she is so proud of taking. She and the rest of the community, queer or not, will, for now at least, continue to benefit from the work of Casa 1 — the country’s political climate notwithstanding.

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation’s Rainbow Fellow at the M&G