Some of the most publicised events about the movement happened at Wits and as its vice-chancellor, Adam Habib was often in the eye of the storm. (Waldo Swiegers/ Gallo)

The most striking feature of the once-hit TV show House of Cards is its use of asides. In the midst of some or other political spectacle, Frank Underwood, a ruthless, ambitious, power-seeking American politician, who tramples on anyone who stands in his way, breaks the fourth wall to reveal the truth.

Although Underwood’s character is explicitly duplicitous, he invites the audience in, turning you into a co-conspirator, making him seem somehow more reliable. He sees the political game for what it is, partly because he is at the centre of it.

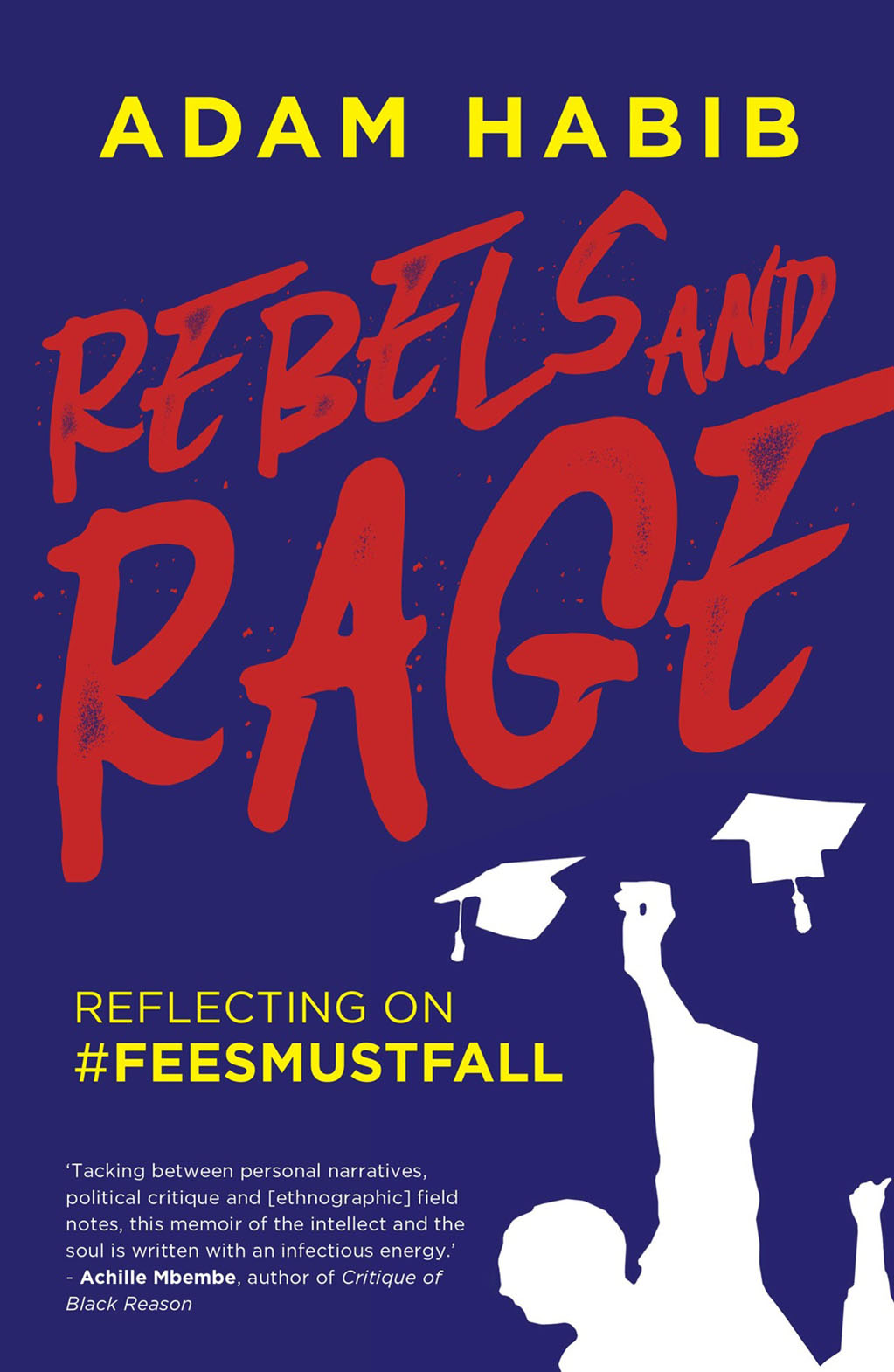

Adam Habib, in his book on the student movement that swept through the country in 2015 and 2016, adopts a similar strategy. Taking his reader into his confidence in Rebels and Rage: Reflecting on #FeesMustFall, he reveals clearly the pitfalls of the political chess game that the protesters were playing when they called for free, decolonised university education.

(Jonathan Ball Publishers)

His memoir style draws you in immediately. It’s a unique way of telling the story of the movement, when students took on their universities for their perceived failure to assure access to higher education for all.

As the vice-chancellor of the University of Witwatersrand, Habib uses his firsthand knowledge of the movement to seemingly lay bare its ironies. As he sees it, its most glaring paradox lies in the fact that the students were setting alight institutions in the name of a cause that was economically untenable.

Some of the most publicised events about the movement happened at Wits and Habib was often in the eye of the storm, seen sitting cross-legged on the floor of Senate House.

Even if he was at times painted as the enemy, his position makes his account almost automatically reliable, especially for those similarly alienated by the often brash tactics of the other side.

Habib uses Rebels and Rage to show how he was forced to walk a diplomatic tightrope, caught between his own imagined progressive ideals and wanting to preserve his seat of power by protecting the university from inevitable financial destruction.

This is no doubt a worthwhile contribution insofar as it reveals the bureaucratic challenges faced by the management of the universities when the student movement was at its most feverish. There are parts of Rebels and Rage, particularly the chapter that deals with the challenges that accompanied the implementation of insourcing, that could probably serve as a blueprint for containing a managerial crisis of conscience.

The book begs for a similar account by the other side; about the political hurdles faced by students coming to grips with organising mass action. The historical narrative that Habib deploys so impressively is a necessary departure from the often alienating language of theory that has become associated with “fallism”.

Habib also manages to assert his authority by being seemingly fair in his assessment. He shows that he understood where the different players were coming from, and makes sure to highlight the small acts of humanity that happened below the spectacle.

He chalks up the perceived unkindness of his adversaries, student leaders like Shaeera Kalla, Vuyani Pambo, Nompendulo Mkatshwa and Mcebo Dlamini, to misguided political opportunism.

That doesn’t mean Habib shies away from delivering some scathing rebukes of them — he calls Kalla two-faced, for example — but he does generally acknowledge them as an astute opposition.

However, he does tend to vilify one group of players, the so-called “far left”.

In Rebels and Rage, Habib is at pains to define them, which at Wits were mainly academics from the social sciences faculty. This preoccupation with identifying and criticising the far left is an explicit attempt to separate himself from what he deems destructive radicalism, while still positioning himself on the left.

In particular, Habib takes on Professor David Dickinson who, in October 2015, voted against a proposal to increase university fees by 10.5% and who has engaged in a number of public spats with Habib since then.

Habib also singles out Eric Worby, an academic who sided with the workers in their call for insourcing. Strangely, he accuses Worby of not being committed enough to his cause because the academic failed to personally take on the duty of drawing up an insourcing plan.

In doing so, Habib puts the responsibility of transformation on the shoulders of the protesters, suggesting that it is in their best interest to save the university from itself.

This is not how protest works. The bosses must adjust to save themselves, or risk shattering the image of the benevolent university.

This is the major irony of Habib’s project: although he accuses the other side of romanticising revolution and violence, he falls into the trap of overestimating the importance of the university in protecting South Africa’s democracy.

Habib lambasts his colleagues, striking workers and students for not wanting to contribute to the preservation of the university but he fails to show that the student and worker protests took on the very idea that ivory-tower institutions have the will to protect so-called stakeholders from the indignities of capitalism.