(Jessica Bordeau)

COMMENT

Nokuthula*, 43, had been a member of South Africa’s largest medical scheme, Discovery Health, for eight and a half years. She’d religiously paid her premiums each month while also managing to — like many South Afri- cans — financially support elderly family members. That is until financial constraints forced her to leave the scheme and spend eight months without any medical cover.

But then Nokuthula unexpectedly fell pregnant.

The first-time mother’s excitement was cut short when she found complications might place her and her unborn child at risk. She immediately rejoined Discovery, and they accepted her and her premiums.

But upon rejoining, she was told that her pregnancy was considered to be a pre-existing condition and that she would be unable to claim for any care in relation to “the condition” for 12 months — in effect precluding her from claiming any costs for the pregnancy and birth. No delivery costs would be paid outside emergency care, the scheme told Nokuthula. The child, her dependant, would be covered from birth only.

The news was devastating for Nokuthula both medically and financially. For an expecting mother already dealing with a difficult pregnancy, word of the policy led to the kind of additional stress, anxiety and debt that serve to only harm a person’s pregnancy, not enhance it.

To ensure that her baby would be covered once born, Nokuthula paid her full monthly premium to Discovery during her pregnancy even as she forked out thousands of rands out of pocket for specialist care to ensure a safe pregnancy and healthy baby.

Initially, ill-advised that the state would be unable to offer the specialist care she needed, Nokuthula shared her predicament with me by chance, and the public health network that I often rely on for my advocacy work sprang into action, offering medical advice and public sector referrals This, coupled with her GP’s support, enabled her to receive advanced, specialist care at a tertiary academic hospital, resulting in the safe birth of her child, at no additional or exorbitant cost.

Just before that, a private health facility had told Nokuthula it would cost R100 000 to deliver her baby. This is indicative, I believe, of the kind of racketeering that goes on among hospital groups, obstetricians and gynaecologists, and other specialists who take advantage of medical scheme exclusions and waiting periods.

Given her previous uninterrupted membership with Discovery, the scheme could have agreed to cover Nokuthula’s pregnancy if she, for instance, repaid the equivalent of the eight months of premiums she had “missed” after leaving the scheme for a short while in order to “make good” on the period she missed. She had spent almost a decade as a member in good standing who had contributed to the general risk pool of Discovery and even cross-subsidised other members’ medical costs. But when it mattered most, that didn’t count.

Last year, Discovery Health Insurance’s profits soared by 11% as the administrator raked in millions from its new headquarters in northern Johannesburg.

There is a certain irony when the owners of one of the glossiest, shiniest, buildings in all of Sandton tells a pregnant black woman, after more than eight years of continued membership, that they cannot cover her “pre-existing condition” because she took too long (read: five months) to rejoin.

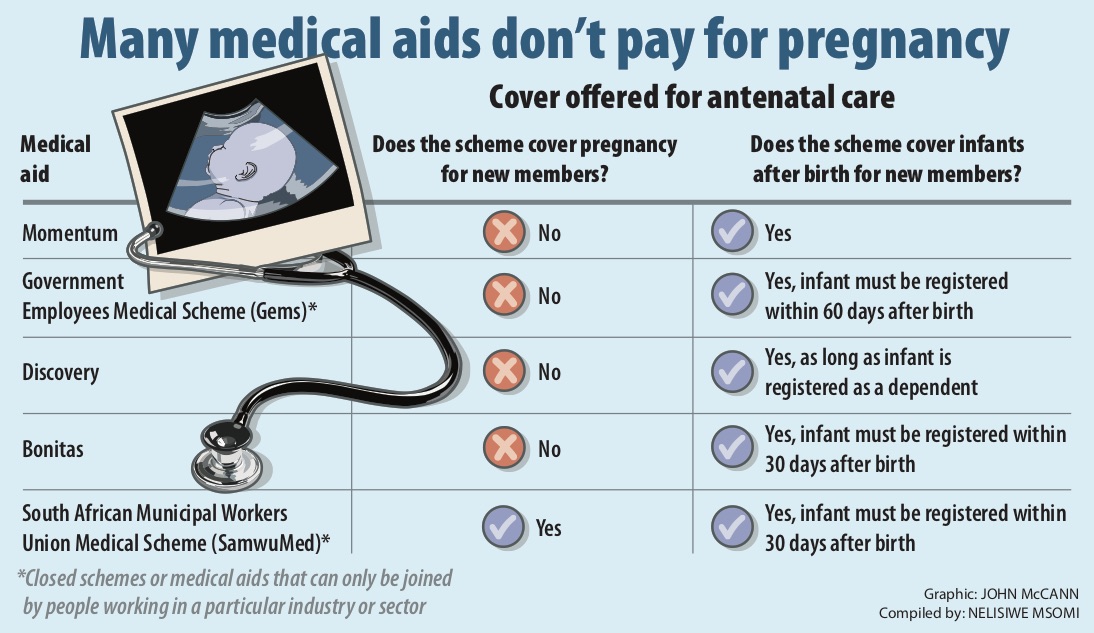

And, our law allows this and Discovery isn’t the only culprit refusing to pay for new members’ or re- joiners pregnancies.

By law, medical schemes must cover a set of 270 conditions called prescribed minimum benefits (PMBs), regardless of what kind of plan a member has. The Medical Schemes Act of 1998 introduced PMBs to help safeguard consumers from losing medical cover in the event of serious illness. This loss would not only be unfair, but would also push more patients, but not additional funding, into the public health system.

So PMBs were introduced to also improve efficiency in the allocation of private and public healthcare resources, the Act explains.

But today, despite the government’s commitment to reducing maternal mortality, antenatal care still isn’t a PMB. However “antenatal and obstetric care necessitating hospitalisation, including delivery” is a PMB, according to the full list of PMBs stated on the Council for Medical Schemes website.

The Act also established South Africa’s first Council for Medical Schemes (CMS), a statutory regulatory body created by Parliament to regulate the sector, at the end of apartheid.

The new CMS also marked the end of an era in which member premiums were determined partially or entirely by how much patients with health conditions were likely to claim. This system, known as risk rating, penalises people with health conditions.

Not everyone was happy about the shift and it was strongly opposed by vested private sector interests including Business South Africa, the predecessor to Business Unity South Africa.

I was privileged to serve as a CMS board member between 1999 and 2001 because of my work campaigning for the rights of people living with HIV. I served alongside the visionary leadership of people such as the then director general of health, Ayanda Ntsaluba, now the chief executive of Discovery Holdings, and the registrar of medical schemes at the time, Patrick Masobe. With them, the council’s inaugural members and staff worked to set up a structure to give effect to the regulatory framework, free from vested interests and influence.

The ANC introduced the 1998 reforms as part of its vision to eventually do away with the country’s two-tiered health system that divided users unequally among the private and public sectors based on race and income. They also served to regulate what was, at that time, a handful of private medical “aids” that existed mainly for white South Africans who could afford it.

It took massive legal battles and public campaigning against business interests to get the industry to align with the goal of social solidarity — the idea that healthier members should cross-subsidise those with greater health needs — to eventually, one day, roll out universal health coverage.

Finally, your health status would no longer solely determine whether you could join a medical scheme. Your income, however, still did.

In return, the industry was permitted to implement late joiner penalties and general waiting periods (three months). Longer waiting periods for pre-existing conditions that do not appear on the PMBs were also allowed and, incredulously, included pregnancy. During general three-month waiting periods, new members pay monthly premiums but are not entitled to any benefits, in some instances not even for PMBs.

Ultimately, these concessions to the industry not only remain in our law but have been expanded by smart lawyers, actuaries and consultants working for the medical scheme industry who have, in effect, bullied the regulator and the department of health into acquiescence. This is in part due to threats of legal action against the state; threats in effect made against women, who shoulder the financial costs of bearing a healthy child because of these decades-old compromises.

It’s time to challenge these concessions because until the National Health Insurance is fully rolled out, many working women who can afford to, will rely on basic or entry-level medical scheme plans. They do so to save time in queues, to travel shorter distances to a clinical facility near their work or home, or to get tested and screened in a clean facility at fixed times that make sense for their work commitments and family obligations. Not least of all, they do so because most state facilities are overcrowded, under-resourced and often experience staffing and medicine stock-outs and shortages. The state has also failed to tell the incredible story of some of its centres of excellence, so many people still believe that private is best.

The time has come for civil society and progressive, committed health professionals and medical schemes — with government support — to change the law and the rules.

The medical scheme leadership — and people such as Discovery’s Ntsaluba, who for so long fought with us — should step up and do the right thing: protect women, not profits.

We must also call on the new Parliament to urgently convene a national commission of inquiry into the pricing practices of specialists in the sector — though civil society and women’s rights coalitions will likely have to fight this battle alone.

*Not her real name

Fatima Hassan is a social justice activist and the executive director of the Open Society Foundation for South Africa. She is a former member of the Council for Medical Schemes (1999 – 2001) and served as special adviser to former health minister Barbara Hogan in 2008. She writes in her personal capacity. Follow her on Twitter @_HassanF. The Council for Medical Schemes did not reply to requests for comment.