(John McCann/M&G)

NEWS ANALYSIS

Science is giving us less and less time to get our climate act together while observable weather patterns, whether it is drought in the Western Cape or cyclones in Mozambique, tell us that climate breakdown is already here.

The erratic weather, and a warning from the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in October last year that we have just 12 years to limit a climate change catastrophe, have brought new urgency, with investors increasingly demanding that climate risk is evaluated when investment decisions are made.

The BHP Group, the world’s biggest miner, said this week it won’t add to thermal coal production because it prioritises growth in commodities tied to the shift to renewable energy and electric transport, Bloomberg reported.

There’s the prospect that [thermal coal] will be “phased out, potentially sooner than expected”, chief financial officer Peter Beaven told investors on Wednesday. The Australia-based producer has “no appetite for growth in energy coal regardless of asset attractiveness’’, he said.

BHP follows its biggest competitors, Rio Tinto and Glencore, in questioning the future role of coal used for power generation, as investors press for more action to tackle climate change and tighten restrictions on holding companies that produce the fuel, Bloomberg reported. Rio sold its final coal mines last year, whereas Glencore said in March it would seek to limit production.

Three South African banks have said they are not prepared to finance two coal-fired independent power stations (IPPs).

We are in a brave new world where low carbon is in, fossil fuels out. But what does this mean for an economy such as South Africa’s, where power utility Eskom uses coal to produce 90% of our electricity and Sasol’s coal-to-liquid plants are one of the world’s single largest sources of carbon dioxide emissions?

Coal is also an important export earner for the country — R60-billion in 2017 — and 100 000 people are employed in the coal-related sector.

South Africa, along with 180 other nations, is signed up in terms of the Paris Agreement to limit carbon emissions in order to curb the rise of global temperature to well below two degrees centigrade.

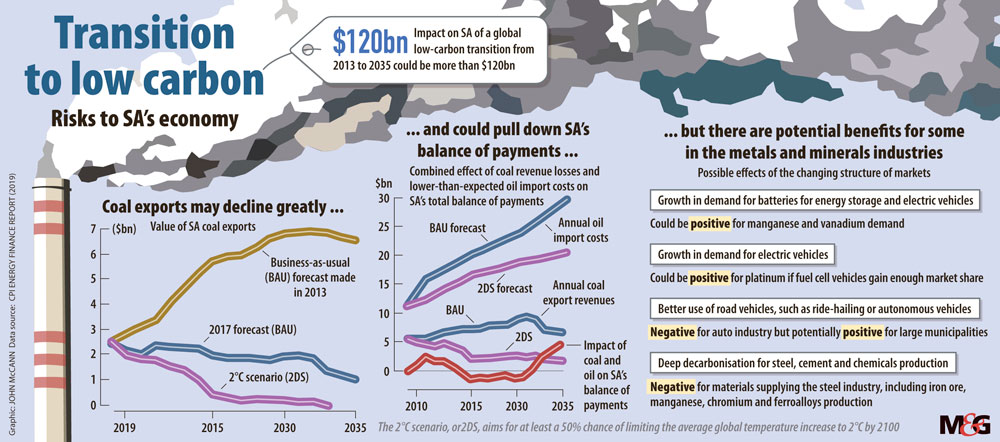

But how much will a transition from high to low carbon cost? Indeed, is such a transition even possible for coal-intensive South Africa? A 153-page report by think-tank Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), Understanding the Effect of a Low Carbon Transition on South Africa, quantifies the country’s transition risk — the value of assets and income less than expected because of climate policy and the switch from coal-fired power — at R1.8-trillion by 2035.

Commissioned by Agence Française de Développement and the Advisory Finance Group of the World Bank and released last month, the CPI report identifies $25-billion of current fosssil fuel projects now in planning or under way, which it says will add to the transitional risk.

“The current South African system of incentives for new capital investment favour some existing industries that are exposed to climate risk.”

These include the expansion of rail lines between Mpumalanga and Richard’s Bay and to the Waterberg, rail links to Swaziland and Botswana, the two coal IPPs, Thabametsi and Khanyisa (which the three local banks are refusing to fund), new coal mines in Limpopo and Mpumalanga, and a new oil refinery in Limpopo.

The CPI report argues that rather than projects that add to transitional risk, investments should be pursued in new sectors that may create more sustainable sources of jobs and economic growth.

It evaluates the risks for both private and public sectors and, although private companies such as coal miners are vulnerable, it says much of the risk will ultimately be borne by government.

“A global low-carbon transition could reduce the demand and price for assets including carbon-intensive fossil fuels such as coal and oil. Infrastructure that supports higher carbon activities, including rail, power plants or ports built around fossil fuel industries, may have to be replaced or retired early.

“Companies, investors and workers could be hurt by lower prices and reduced demand for certain products. Government may face reduced revenues, for example from lower tax receipts, while their expenditure increases for financial assistance to industries and workers in transition.”

The report notes that trade-offs associated with a low-carbon transition will be particularly acute in South Africa, “a country associated with high levels of unemployment and inequality and an ambitious development agenda”.

It considers various restructuring options for Sasol’s Secunda plants, but concludes that the least-cost route will probably be to shut these down. The CPI suggests prioritising R&D funding into low carbon alternatives, which might bring down the cost of replacing the plant a few years down the line.

The CPI says policy in countries such as China, India, the United States and those in Europe to reduce coal use to comply with the Paris Agreement, will disproportionately affect internationally traded coal. Both the volume of coal sold and its price will fall, affecting miners and export-oriented infrastructure.

This means substantial risk for state enterprise Transnet, which moves large volumes of coal to the coast for export.

Transition risks, the CPI report says, will accumulate slowly in the coming years before accelerating in the mid-2020s.

It stresses that decarbonisation brings opportunities as well as risks, but argues for proactive policy to be able to maximise the former and minimise the latter. Opportunities include the adoption of renewables, a low-cost source of energy for South Africa with its abundant sunshine. The country also stands to benefit from increased demand for minerals such as platinum and manganese for use in low-carbon technologies.

One mooted silver lining for South Africa is that oil prices globally are expected to fall as the world switches to electric vehicles, the CPI putting this figure at $40-billion.

“Lower oil prices could dampen the effect on falling coal exports on the balance of payments.”

The report says the largest share of the risks come from factors that are beyond the control of South Africa itself, including changes to coal and oil markets that will be driven by global demand, but nevertheless proactive government responses to those risks beyond its control can help it mitigate the effect.

Bloomberg, in an analysis published this week that considered new coal power station development, pointed out that such stations are closing faster than new ones are being built. The last coal power station will soon be built, the article concluded.

Coal exports currently provide profits, royalties and tax receipts for South Africa when the revenue from selling the commodity exceeds production costs. Revenues from coal sales also pay back sunk capital investment in mines and the rail and port infrastructure that is needed to get the coal to the market. This could lead to a fall in government revenues and debt defaults that might cascade through the economy.

Some mine owners may decide to close assets before the end of their economic lives. Mine closure will hit people and workers through job losses, reduced economic activity and the loss of funding from companies for social infrastructure. Municipalities where assets are located may be the hardest hit.

Government could find itself faced by sharply increased costs because of either bailouts or decommissioning costs after bankruptcy.

The CPI estimates government’s direct exposure to transition risk at 16% of its balance sheet, but says contingent liabilities and other indirect exposure means its actual risk is more than three times this; that is, more than half.

Government needs to take stock of the rapidly changing market for commodity exports and adapt development and financing plans accordingly; avoid or delay new investments that could add to South Africa’s climate risk exposure, shift capital expansion to sectors more resilient to transition risk or benefiting from the exposure; clarify responsibility for $38-billion of climate transition risks where the bearer of the risk is currently unclear or not explicit; manage the timing and speed of climate mitigation actions and commitments to avoid compounding shocks to the economy; and plan to manage risk to the vulnerable parts of the economy.

Caveat emptor, let the buyer beware, is a watchword of commerce. Decarbonisation means that for business as usual, for governments and investors, what may have worked in the past, is unlikely to do so in the future.

The CPI analysis suggests substantial risks are involved and that at a minimum the transitional risk associated with fossil fuel projects needs to be transparently identified so that it can be properly costed to accelerate the switch to renewables and other more sustainable options.

Let the investor beware.