Today Dr Gérard Labuschagne is the director of L&S Threat Management. (Hiram Alejandro Durán/M&G)

“I often don’t like to tell people what I do,” forensic psychologist Gérard Labuschagne says, leaning back comfortably in his seat at the Mail & Guardian’s offices in Johannesburg. He’s here to talk about the successes of South Africa’s forensic profilers — a 100% conviction rate.

“If I’m out, I dread the question: ‘What do you do?’ I try to avoid it. When I was in the police service, I would just say I’m a policeman and people would just stop talking to me.”

Labuschagne is dressed in a slick blazer and is toting a khaki green backpack. His steely demeanour, an effect of his bald head and blue eyes, softens when he speaks.

He headed up the police service’s investigative psychology section (IPS), South Africa’s equivalent of the FBI’s behavioural analysis unit, for 14 years, before he resigned in 2016.

That is part of his problem; behavioural analysis is a field plagued by Hollywood tropes. When people find out that he is a profiler, like Jack Crawford in the film The Silence of the Lambs, Labuschagne must field the inevitable questions about his penchant for true crime films and books.

Talking about the gulf between the way things are done in the movies and how it works in real life, Labuschagne’s words snap with derision.

His conversation goes from the difficulties of what was a sometimes thankless job to the small triumphs of being part of a team tasked with helping to solve some of the country’s most serious crimes.

Local profilers

Forensic psychologists work with the police to profile and track down offenders. The profile allows police to start guessing a killer’s next move, so they can catch them. The profile of American serial killer Ted Bundy, compiled by the FBI’s Robert Ressler, led to his capture in 1978. Ressler, who is credited with coining the term “serial killer”, believed Bundy looked for young women with long hair parted down the middle. He said Bundy hung out at bars, ski resorts, beaches and other locations where young people gathered. Five days after this profile went public, authorities in Florida arrested Bundy.

Labuschagne worked on 110 serial killer cases at the police’s investigative psychology unit, set up by forensic psychologist Micki Pistorius (Liza van Deventer/ Foto24/Gallo Images)

Acclaimed South African forensic psychologist and author Micki Pistorius met Ressler in 1995, a year after she founded the IPS.

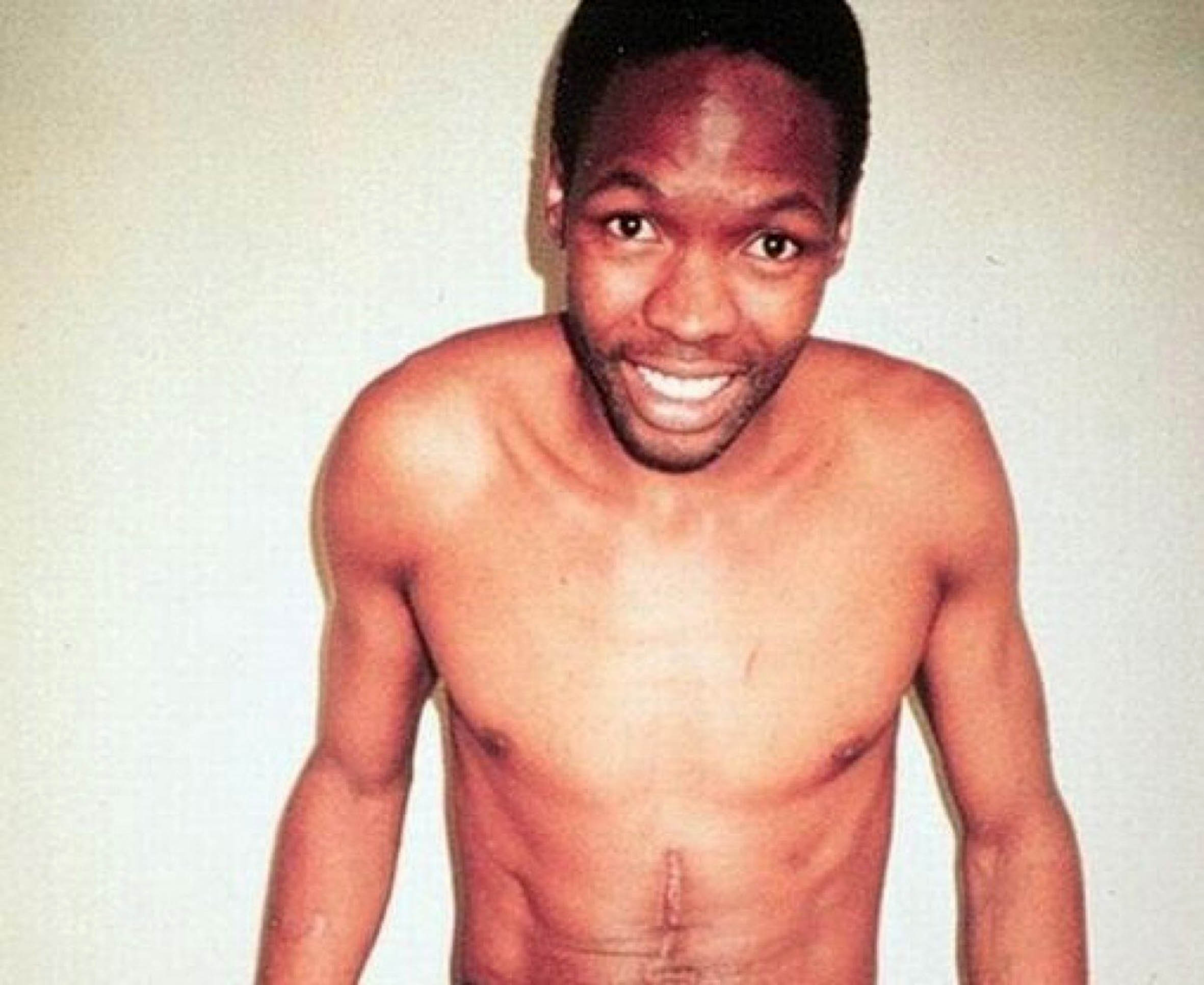

Pistorius profiled some of South Africa’s most prolific serial killers, including Moses Sithole, who committed at least 38 murders and 40 rapes. Pistorius’s profile predicted that Sithole would contact the media. In 1995, Sithole contacted The Star under a fake name and confessed his crimes.

Top killer: Moses Sithole was convicted of 38 murders and 40 rapes in 1997. Psychologist Micki Pistorius helped develop a profile of him

During her six years at the helm of the IPS, Pistorius trained more than 100 detectives in investigating serial murders.

Although the IPS may have had an illustrious beginning, it has

also not been immune to the problems of underfunding and skill shortages other law enforcement units have encountered over the years.

The unit, made up of psychologists and detectives, has had trouble retaining experienced investigators, who, according to a 2018 Sunday Times report, have left amid complaints about low pay and heavy caseloads.

The newspaper’s article also carried a startling but contested ranking that puts South Africa third on the list of countries with the most serial killers and rapists, behind the United States and Russia. The Radford University and Florida Gulf Coast University serial killer database, which has information on 4 068 serial killers and 11 680 victims since the early 1900s, also puts South Africa third on the list of countries with the most serial killers, but behind the United States and England. According to the list, South Africa has had 117 serial killers between 1900 and 2016.

But these lists have their problems — often killings haven’t been linked together, and some countries don’t have the investigative skills to work out that there is a serial killer in action.

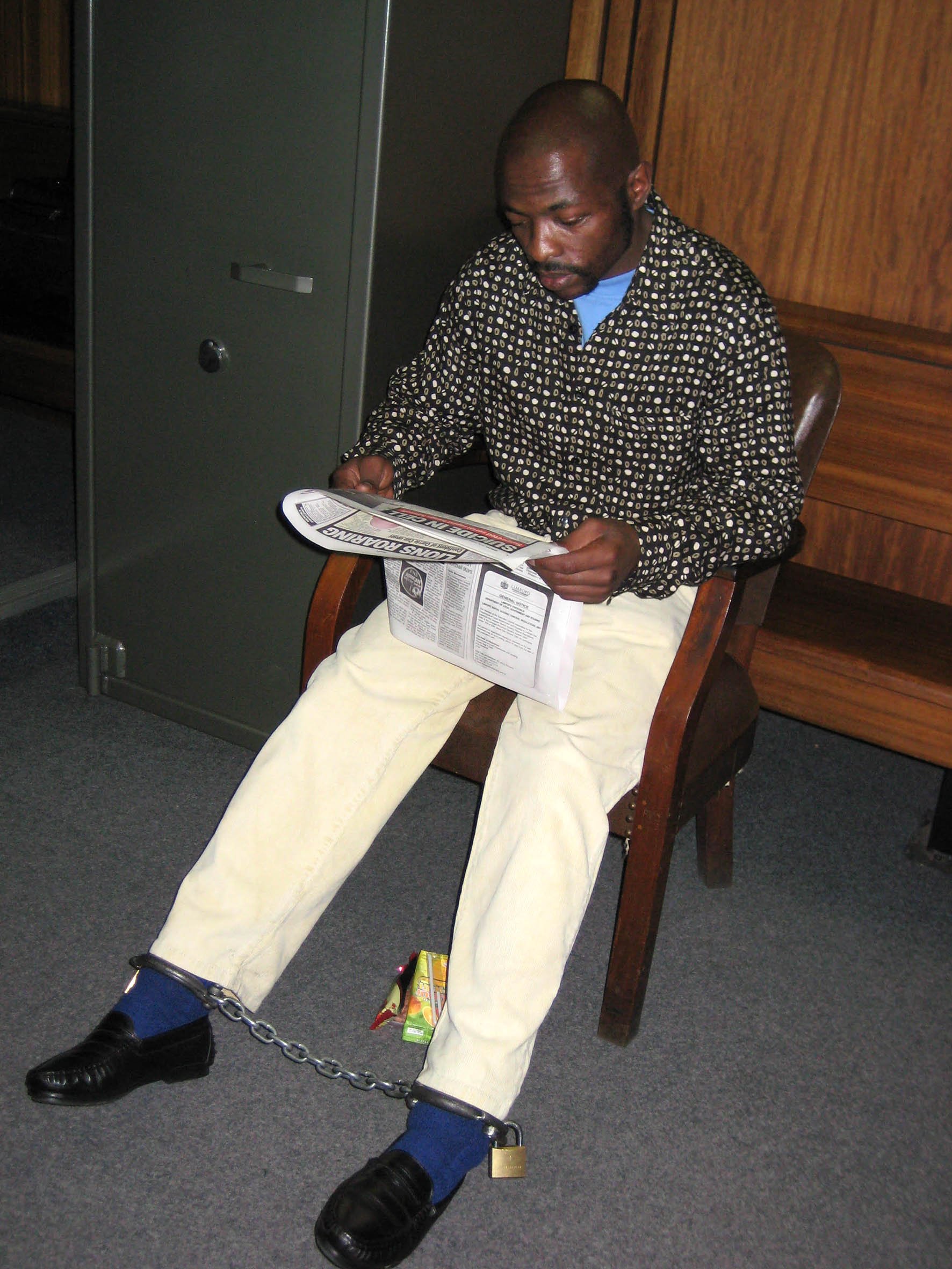

Labuschagne says that during his time in the police service, he worked on 110 serial murder cases, including that of ‘Quarry murderer’ Richard Jabulani Nyauza. When his sentence of 16 life terms for a series of gruesome murders in 2002 and 2006 was handed down, Nyauza smiled and said he “felt nothing”.

“It changes nothing,” Nyauza said before being led down to the cells.

Before his descent, he took the time to shake Labuschagne’s hand. Labuschagne was responsible for linkage analysis resulting in Nyauza’s conviction on all 24 charges against him. With his 110 cases, Labuschagne has probably encountered far more serial killers than his colleagues abroad, he says.

Quarry murderer: Richard Nyauza wore in court a pair of pants given to him by investigative psychology unit head Gérard Labuschagne.

Being able to count the number of serial killers South Africa has had is a testament to the success of the IPS and the country’s DNA database, according to Labuschagne. “We have the ability to have a fairly accurate record … We have a lot [of serial murders], we know that. And we can show you that we have a lot.”

Thanks in part to the database, the IPS has a strong reputation for catching serial killers. Labuschagne confidently says: “No one has ever walked out of a court and was found not guilty.

“I think over the years that what we did, and how we did it, worked. We had a very good success rate in solving serials. We have never really had one who continued to kill that we didn’t catch.”

A career in profiling

Labuschagne says the unit’s reputation is bolstered by its training and research output.

It runs a three-week course to train detectives in how to identify and deal with psychologically motivated crimes — serial murders and rapes, paedophilia and intimate partner murders. Labuschagne says that the South African Police Service is the only law enforcement agency in the world that regularly runs these types of intensive training courses.

During his tenure, the unit was also part of the largest study in the world, using police case files, when it teamed up with the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York in 2014 to assess the types of serial homicide in South Africa. The sample for the study consisted of 302 offences

committed by 33 offenders that occurred in the country between 1953 to 2007.

Labuschagne, who has provided training to Scotland Yard and the FBI, talks about these achievements with dry candour — avoiding any sugar coating of how tough a career it is. “You’re asking people to do a very horrible job, with no career path and in which every time you step into a court you risk your reputation being destroyed. You see really horrible stuff … And then they go: ‘All this shit and I’m earning less than an intern.’”

Not everyone has what it takes. “Your brain has to work in a particular way to be able to solve certain puzzles,” Labuschagne says.

Getting the right people is becoming more difficult, with forensic psychology in law enforcement becoming “probably a dying thing”.

It’s also a career that people drift into. Labuschagne says that because much of what goes into criminal profiling is learned on the job, many of the people who have ended up working at the IPS are detectives without university degrees.

“It is very difficult for people to know what the job is about, specifically the psychologists. Policemen know. They’ve seen murders and they have been to crime scenes and autopsies.”

As he talks, Labuschagne gestures for emphasis, each one threatening to topple the cellphone on the armrest recording the interview.

“It’s different for a psychologist, who has watched a lot of TV and thinks it’s so cool. Then they come here and they have to deal with the frustrations of being in the police and they have to go to autopsies and sit in court and go to crime scenes. So some of them don’t last very long … It’s not for everybody.

“But you get people who are just able to deal with it longer.”

The personal cost

The tough parts of the job are accompanied by the rush of working on complex cases, Labuschagne says, calling his time with the police service “the most fun 14 and a half years” of his life.

Although he isn’t the archetype of the brooding detective, he says that the years of being privy to the details of some of the country’s most gruesome crimes have taken their toll. This is part of the cost of helping South Africa to successfully track down its serial killers.

“I don’t think that even if you love it and it is fantastic, you would be naive to say that it doesn’t affect you as a person.”

After leaving the police, he realised he was operating at a high level of stress and tension that had become his daily norm.

“I think there was a form of PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. But not the type where you wake up in the middle of the night with nightmares and flashbacks,” Labuschagne says. He adds: “Now I’m definitely a lot more relaxed.

“I’m not saying that I love people in general. And I’m not the warm, outgoing person I was 15 years ago.”

Serial killers with the highest known victim count

The art of unmasking the hunters of humans

Little is known about the true numbers behind serial killings.

Independent fact-checking organisation Africa Check says there’s no way to figure out those odds as yet. Doing so would need to take into account both probability and the state of data on multiple killings.

What we do know is that if someone is killed by a hunter of humans this is a good country in which to get the case solved. South Africa is home to some of the best behavioural analysts, more commonly known as profilers, in the world.

This criminal profiling occupies the intersection between psychology and law enforcement. It is based on the premise that behaviour reflects personality: what a criminal does or leaves at a crime scene can help to identify them through their mental, emotional, and personality characteristics.

The American Psychological Association says that early criminal profiling was used in the 1880s, when British police surgeon Thomas Bond of London’s Metropolitan Police attempted to make inferences about the personality of one of history’s most prolific and as yet unidentified serial killers, Jack the Ripper.

The formal emergence of the discipline only came about in 1972, when the FBI’s behavioural science unit was created. This unit began to investigate the rising tide of serial rapes and murders across the United States. The profilers did this by examining four crucial aspects of suspected criminals’ behaviour: antecedent (that is before the crime has occurred) tendencies, manner of crime, body disposal method, and post-crime behaviour.

Since then, the techniques of criminal investigative analysis have advanced, allowing the FBI and other law enforcement agencies around the world to develop offender profiles in a range of crimes such as arson, hostage-taking, terrorism, child abduction, white collar crime, kidnapping, extortion, cybercrime, and serial sexual homicide. The common thread is that these are all psychologically motivated crimes.

In 2015, the FBI hosted a serial murder symposium to work out an internationally accepted definition of “serial offence” — there wasn’t one. The FBI defines serial killing as “a series of two or more murders, committed as separate events, usually, but not always, by one offender acting alone”. More than 130 experts from 10 countries, including South Africa, agreed on this definition for serial murder: “The unlawful killing of two or more victims by the same offender(s), in separate events.”

There are other, less formal, definitions of who constitutes a serial killer. These include a person who murders three or more people, usually in service of abnormal psychological gratification, with the murders taking place over more than a month and including a significant period of time or “cooling off period” between them.

Last year, the Sunday Times newspaper made the claim that: “South Africa ranks among the world’s worst three countries – after the United States and Russia — for serial murders and rapes.” A similar claim was made in a 2006 article — although the claim only referred to serial murders.

Africa Check delved into the claim and has cautioned against such comparisons on the basis of a number of factors — such as the fact that definitions of serial offences differ, as do legal definitions for rape and murder.

In addition, many databases use media as sources of possible cases, which may erroneously take into account murders that are not necessarily a part of a series because of differing definitions of serial murder.