The SALT, like the SKA, is in the Northern Cape. New rules mean aircraft may have to avoid the area. (Mujahid Safodien/AFP)

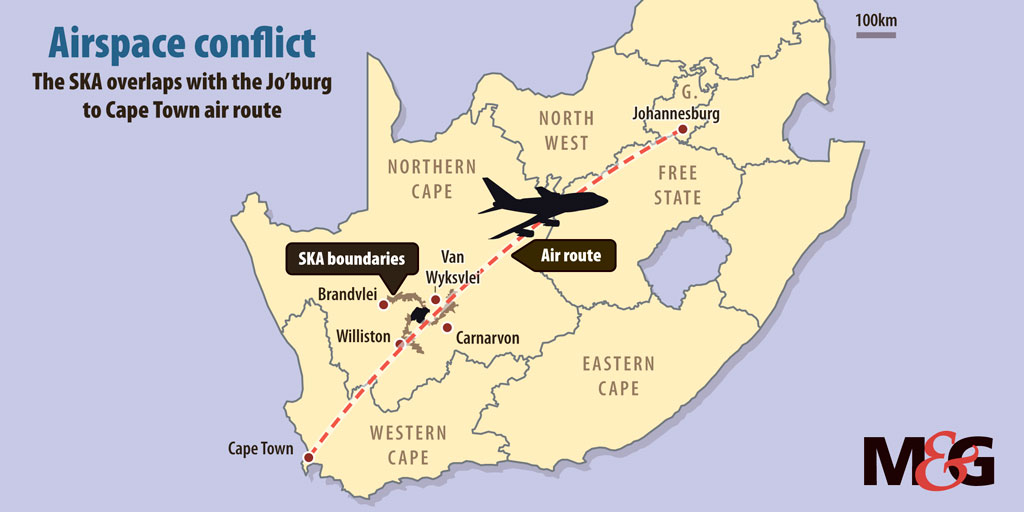

New regulations due to come into effect on December 15 this year, which will prohibit the use of part of the radio spectrum above the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) in the Northern Cape, have the airline industry asking what this will mean for the country’s and the continent’s busiest air route.

Aviation is excluded from these regulations for now, but the industry is concerned about the lack of clarity about its operations after December. There are even concerns that aircraft may be expected to skirt the area, perhaps adding as much an hour to the flight between Johannesburg and Cape Town.

The route has about 55 domestic passenger flights a day, and is also used by international airlines flying between Cape Town and the Gulf.

The SKA, which will contain thousands of antennaes, is located near Carnarvon. A map on the SKA website shows its core area will be about 40km by 40km, with a wider area of spiral arms of about 100km each. Scientific observations, using a partial array, will begin in the mid-2020s.

Independent aviation consultant Linden Birns said, if airlines have to re-route flights to skirt the SKA, the costs will be passed on to passengers and air cargo shippers, pushing up the cost of doing business and harming the economy.

He said re-routing, possibly through Botswana, could add as much as an hour to the flight time, with longer flights also incurring additional carbon tax charges.

Birns said the SKA has to avoid external frequencies to function optimally. “The South African bid team knew that it would require airspace within which nothing else could transmit signals on those frequencies except for the SKA’s own instruments. This meant creating a pristine radio area.”

There is concern in aviation circles that not much is being done to address these issues, he said.

A stakeholder meeting hosted by the department of science and technology in October 2016 on draft regulations on the Karoo Central Astronomy Advantage Area resulted in a joint task team being created to find a technical solution.

“By March this year the task team had not yet met. My latest information is that a meeting was convened a few weeks ago, but it was unable to report any progress,” Birns said.

Adrian Tiplady, head of strategy at SKA South Africa, said a solution should be found by all those involved. He said the next step concerning aviation will be promulgated by the ministers of transport and science and technology. In the meantime, relevant stakeholders in the aviation sector will be engaged to assess the “impact of radiation and of flying aircraft directly or 10km away from the telescope. Then, after understanding that, we will say how we can mitigate the problem,” Tiplady said.

The aviation sector is best placed to find solutions jointly with the SKA, he said. “We need to understand the technical details of the actual impacts first and those mitigation measures we need to develop together with the aviation sector.”

Once the technical impact is described, the parties can jointly decide on how best to mitigate the impact of the SKA.

Birns said, however, that “From what I’ve been able to gather, because SKA is regarded as the country’s most prestigious scientific endeavour, there is reluctance within the [department of transport] and the South African Civil Aviation Authority to do or say anything that might embarrass the government.”

The departments of transport and science and technology said it has been noted numerous times that the SKA will not have an “adverse” impact on aviation. The two departments are currently formalising mechanisms in the form of a steering committee and technical working groups.

“These groups will be tasked with conducting research in order to explore possible mitigating measures and determine solutions that could be implemented to protect the interests of the aviation industry, international safety standards and the SKA,” transport department spokesperson Collen Msibi said.

Arthur Bradshaw, formerly South Africa’s head of air traffic control and now a consultant advising several countries on airspace management, said: “We do not know [how aircraft will operate]. We’ve been told they want to use the frequencies that are used for [the] safety of aviation and that means the aircraft will be flying in a way they would not want to operate.”

Bradshaw is sceptical about the environmental research conducted before work began on developing the telescope. “When they did their environmental impact study they clearly looked at the terrain horizontally and nobody bothered to look up into the sky at what is happening above. Somebody woke up afterwards and realised, hey, there is air traffic in this space,” he said.

“You have an aviation industry based on a civil aviation Act, and have standards of recommended practices governed by international protocols, and so you cannot say that aircraft won’t be able to fly there because they switch on a device [the SKA] that is still to be tested. You cannot take an industry that is the lifeblood of South Africa and sacrifice millions of rands and millions of fuel burn for an experimental farm in the middle of the Karoo,” said Bradshaw.

SKA South Africa’s website says the telescope is a global, multibillion-rand project to build “the world’s largest scientific instrument”. The telescope will make use of thousands of radio dishes across Africa and Australia to compile information from space by monitoring faint radio signals given off by stars and galaxies, allowing scientists to expand our understanding of the universe.

The project dates back to 2012 when South Africa, together with eight other African partner countries and Australia, were named as co-hosts for the SKA.

Birns said a notice in April from the minister of science and technology that the use of the radio frequency spectrum from 100 MHz to 25.2 GHz for radio transmissions will be prohibited within the Karoo Central Astronomy Advantage Areas from December 15 2019, but at this stage the aviation industry still does not know the way forward.

Tshegofatso Mathe is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the Mail & Guardian