EFF leader Julius Malema (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

NEWS ANALYSIS

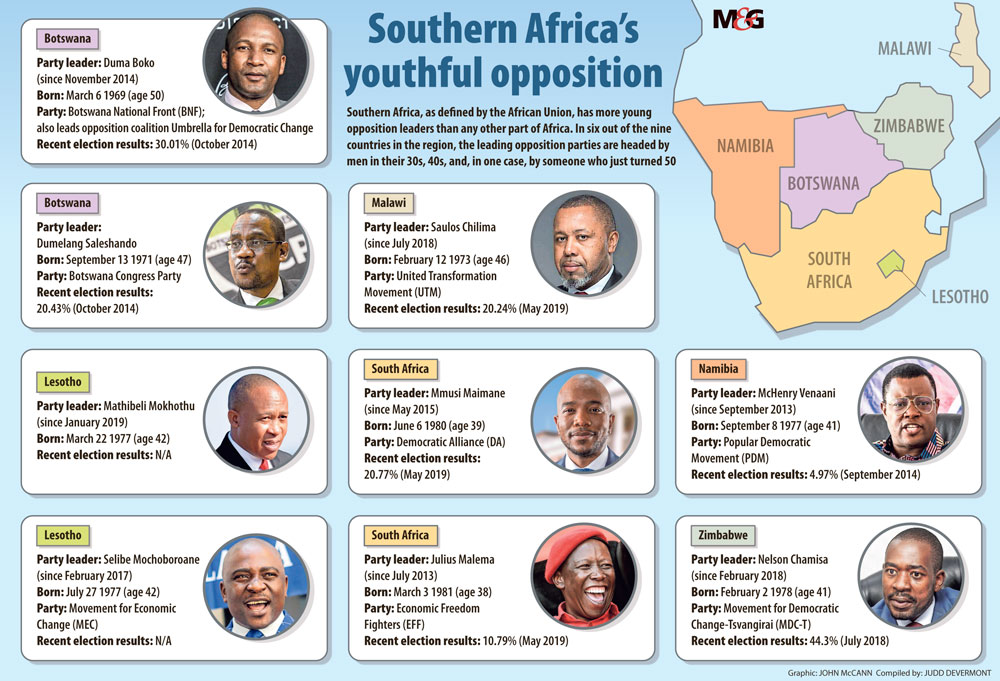

When commentators evaluate the state of democracy in Southern Africa, they consistently overlook one of its most intriguing features: the region’s opposition parties are overwhelmingly run by young men. From Mmusi Maimane and Julius Malema in South Africa to Nelson Chamisa in Zimbabwe, young politicians are at the top of leading opposition parties in six of the nine countries in the region.

This is an anomaly compared with the rest of the continent, and it has implications for political debate and party pluralism. Southern Africa’s young opposition leaders are unseating the elderly elite, injecting new ideas into the political conversation, and increasing competition for national leadership positions. If they start winning at the ballot box, it could have reverberations for peers across sub-Saharan Africa.

The leading opposition parties in Botswana, Lesotho, Malawi, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe are all led by men in their thirties and forties. Duma Boko, who leads the opposition coalition in Botswana, turned 50 this year. Only Angola, Mozambique, and Zambia’s opposition remain in the hands of leaders in their late fifties, sixties, and seventies. On the rest of the continent, it is difficult to identify more than a handful of young opposition leaders. Ugandan musician and politician Bobi Wine, who is 37, is probably receiving the most attention; he recently made a splashy media announcement about his presidential aspirations.

Why are young opposition leaders popping up in significant numbers in Southern Africa? The most obvious explanations don’t fit. It does not seem correlated with youth demographics or an urban-rural divide. If you throw a dart at the map, one will find young opposition leaders in countries with relatively older populations, as well as in countries with younger ones.

The same phenomenon applies to majority urban and predominantly rural societies. Maimane and Malema, for instance, have clinched power in South Africa where the median age is 26 years old and the country is 66% urban, according to The World Bank.

In contrast, Saulos Chilima posted a decent electoral showing in an overwhelmingly rural Malawi, where the median age is 17.

It also does not appear that opposition parties are backing youthful leaders to correct poor performances in past elections. Whether it is Maimane’s Democratic Alliance or the opposition coalition in Botswana, many of the region’s parties had been gaining legislative seats before they elected younger leaders.

Lesotho is an interesting case study. The main opposition has held the premiership twice since 2012, under septuagenarian Pakalitha Mosisili. And yet, Mosisili stepped down earlier this year for the 40-something Mathibeli Mokhothu.

The answer, paradoxically, may be that young politicians are moving into leadership positions because Southern Africa’s opposition parties are weak and fragmented, whereas its ruling parties are strong and hierarchical.

If a young man is in a rush to make a name for himself, he has more opportunities to rise in a small opposition party than wait for a promotion in the ruling party.

And in this region, which Freedom House consistently rates as more free than other parts of the continent, there are fewer barriers to challenging the status quo.

Southern Africa’s opposition parties regularly undergo leadership transitions or splinter into rival factions, providing openings for aspiring politicians to manoeuvre into senior positions. Malawian, South African, and Zambian opposition parties have shuffled through leaders multiple times since 1990s. When Helen Zille resigned as DA leader, the party selected the youthful Maimane to take the helm. This stands in contrast to other regions on the continent: Cameroon and Côte d’Ivoire’s leading opposition parties, for instance, have been under the thumb of a 70- and 80-year-old, respectively, for almost three decades.

The region’s young politicians also routinely strike out on their own, in part, because it is difficult to swiftly ascend to power in many of Southern Africa’s ruling parties. Unlike the rest of the continent, former liberation movements remain in power in Southern Africa, and tend to value conformity over ambition when selecting senior party members. It is nearly impossible to jump the queue.

For example, former Mozambican president Samora Machel’s son, Samora Junior, couldn’t clinch the nomination to lead the party’s ticket in Maputo. Accordingly, it is understandable why Malema quit the governing ANC in South Africa and why Daviz Simango, who at the time was 45, ditched Mozambique’s opposition Renamo a decade ago.

The growing number of young leaders in Southern Africa promises to enrich the region’s democratic debate, increase party competition, and inspire other youthful politicians across the continent. Many of these leaders have attracted new voters and reinvigorated discussions about inequality and the role of the state, even if their contribution has been divisive, as in the case of Malema.

In some countries, the region’s young leaders represent a real challenge to long-standing governing parties. Boko’s party, in coalition with other opposition parties, threatens to unseat the Botswana Democratic Party in elections in October. If the opposition succeeds at the ballot box, it could be shot in the arm for young politicians in other parts of Africa.

On a continent where 60% of people are younger than 24 years old, the possibility of young people participating in and serving at the highest levels of government could be transformative.

Judd Devermont is the director of the Africa Programme at the Center for Strategic and International Studies