The treasury's relaxation of procurement rules will allow the state utility to attend to its ageing power stations far quicker (Paul Botes/M&G)

The mealie fields of Mpumalanga are pretty barren right now, just yellow dust really, making it hard to imagine that anything could grow here. In one such desolate field, about 70 metres from the road, is a large coal truck, deep in the soft sand, hopelessly stranded.

The driver says he was driving at about midnight. His lights were not working well. He went through a stop street, across the road and into the field.

Security issues are a worry at Kusile such as tyres being stolen from waiting trucks. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Security issues are a worry at Kusile such as tyres being stolen from waiting trucks. (Paul Botes/M&G)

In front of the truck, in the near distance, rising like an out-sized symbol of potency, a temple for the industrial age, is the Kusile power station.

Two towers poke holes in the sky and six giant boxes, which house the generators, help define the skyline. Cranes on two of the units indicate they are incomplete.

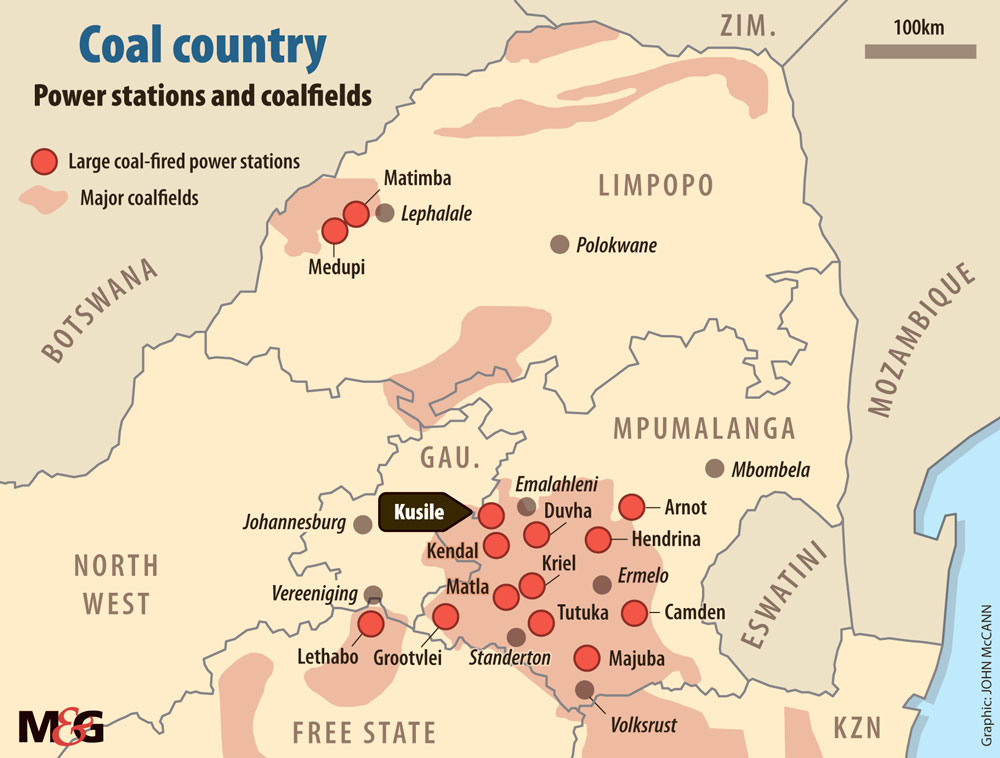

Kusile should be a matter of national pride, a place for proud South Africans to visit, to put on overall onesies and hard hats and tour slack-jawed at the scale and ambition of the thing. But instead, along with its sibling Medupi in Limpopo, it has helped make Eskom an embarrassing joke, bankrupting the utility and threatening to take the country down with it.

I have long since wanted to visit this villain of the piece, to pay personal homage to this monument to folly, a megaproject gone wrong, wrong, wrong.

My immediate reason to visit, though, was a report by Parliament’s standing committee on public accounts on its oversight visit to Medupi and Kusile. Dated October 16, it says the projects, which started in 2007 and 2008, had “been hit by cost overruns, poor engineering designs, labour disruptions and allegations of corruption”.

“The projects were initially budgeted at R79-billion for Medupi and R81-billion for Kusile. Because of delays and other defects identified during and post construction, however, the costs have increased by more than R300-billion, currently reaching R145-billion for Medupi and R161-billion for Kusile.”

The committee said Kusile has six units, but only two have been commissioned. It said coal is delivered by contracted miners near Delmas and Bronkhorstspruit to the stockyard by more than 400 trucks a day for three units.

“This results in congestion and security problems and is a major impediment in the long term viability of the plant. This also results in cost escalation that may not be ameliorated soon.”

(Paul Botes/M&G)

(Paul Botes/M&G)

The 400-a-day equates to 16 trucks an hour every hour for a 24-hour day or one every four minutes. I wanted to see this.

The oversight committee said Kusile’s location was chosen because of its proximity to a coal mine, meaning lower transportation costs. It said that a former agreement entered into by Eskom with a contractor had been cancelled.

“Coal is transported by trucks due to the non-development of the New Largo coal field, located nearby. “This coal field has been sold to Seriti Holdings, and, if negotiations, due to commence in 2020, are successful, this coal field will be developed. This field will be supplying Kusile for a 40-year agreement to supply 12-million tons of coal a year.”

New Largo, on the opposite side of the R545 to Kusile, more or less adjoins the power station. There previously was a mine here which supplied Wilge, a 127-megawatt power station which operated between 1954 and 1990, when it was decommissioned.

Paved with intentions: New Largo, which was sold to Seriti, is set to be developed into an opencast coal mine supplying Kusile power station. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Paved with intentions: New Largo, which was sold to Seriti, is set to be developed into an opencast coal mine supplying Kusile power station. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Wilge is a small settlement with an almost-complete but abandoned 366 apartment block, as well as the headquarters of a mining company. It has substantial security, including three men clad in black with SWAT written on their shirts and riding impressive black stallions, several high-end security vehicles as well as a Casspir-type riot control unit with a water cannon. What they were protecting was not immediately clear.

Anglo American agreed in August last year to sell its New Largo interest to a consortium led by Seriti Resources for R850-million. “The group decided to exit domestic coal productions, partly because Eskom has been asking new suppliers of coal to sell control to black partners, a situation that would lower the attractiveness of low margin, cost-plus mines which New Largo may become,” MiningMx reported.

The property today is rehabilitated, there being few overt signs it was once a mine, but it is largely undeveloped and uninhabited.

A few residents, chopping exotic trees for firewood, said Seriti told them it would be developing the mine. One said mining operations would begin once the top soil had been removed. Another said, based on what Seriti had told them, the earliest hope for jobs would be in 2026.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Seriti’s New Largo development could come at a capital cost of R20-billion, MiningMx reported. The issue is whether it would constitute a brownfields (existing) or greenfields (new) development, the former being more likely to be bankable than the latter, given the growing reluctance by banks to finance new coal.

Asked to comment, a spokesperson said: “Seriti intends to develop a large-scale, opencast mine capable of delivering 12-million tonnes a year to Kusile for a +-50 year period.”

At the entrance to Kusile earlier in the day there was no sign of a truck every four minutes. There were a few about, waiting to enter the facility and add their cargo to the stockpile. But returning at midday there was a queue 20-strong of these giant mechanical beasts.

“Are you waiting to offload coal,” I asked the driver.

“No, we are waiting to collect coal we delivered yesterday,” he said. I gathered there was a problem with the quality.

Nearer the entrance a mechanic was tightening the wheels on a coal truck.

“Why are the trucks collecting the coal they delivered yesterday?” I asked.

“It’s soil,” he replied.

But his truck was not collecting — or delivering — coal. The driver had decided to sleep in the cabin, thieves jacking up the truck’s trailer and stealing four sets of wheels, eight in all, while he slept. We later learned these tyres come at a cost of up to R8 000 a pop.

We may not have seen many coal trucks at Kusile, but there are so many criss-crossing the area you could be forgiven for thinking every third vehicle is a coal truck. A trader we met later told us there were 23 000 coal trucks in Mpumalanga, up from 19 000 in … I did not catch when.

At times we drove past areas of smallholdings, which invariably had one or more coal trucks in their backyards as, in other parts of the country, they may have a dog.

The Kendal power station is visible, just down the road, from Kusile. We headed to a pub for lunch. The Eskom website tells me that Kendal uses dry cooling, which needs much less water. Completed in 1993, it is designed to generate 4 000 megawatts.

If Kusile can average a truck every four minutes, the narrow road feeding Kendal had the coal trucks moving almost bumper to bumper, a pace of several a minute.

The Brompara Pub and Grub is so close to Kendal that you feel you could just run an extension cord and plug directly into it. We asked bartender Ida Court, who knows all things coal because she has all kinds of coal people as her customers, including truckers, traders and equipment suppliers, how many Kendal units were operating. She went outside to check. A light on the top is on when the unit is operational. “Four,” she said.

Court said 400 trucks delivering coal a day is not a lot. “When all six units [at Kendal] are working, it is 600 a day,” she said.

She introduced us to two customers, a coal trader and equipment supplier, who provided a primer on coal basics. New Largo, just over the road from Kusile, can easily supply coal on a conveyor belt, they said, one Eskom belt being 34km long.

We learned that these belts can be in high demand. A recent theft at a coal mine saw the employees being locked up before the belt was cut and the motor turned on, rolling it up for easy transportation elsewhere.

Earlier, at New Largo, I wondered that if Seriti could find R20-billion to put into coal, could the money not better be invested in turning the place into a giant solar farm.

This raises the important issue of a just transition. How can policy minimise the social effect of transitioning to a low-carbon economy, or better still, could clean, renewable energies lead to more investment, growth and jobs?

A study led by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research recommends the coal fields in the Kusile region be developed for solar. Pundits point out that locating solar farms here mean they can cost-effectively be connected to the existing grid with limited transmission losses as the electricity will be used relatively close to where it is generated.

Add a renewable localisation programme, to manufacture renewable technologies, as an investment requirement and the budgeting of special funds for training and re-training, and you have something which gives both the country and the planet a better chance.

Back at Kusile I saw — armed with what I had learned at Kendal — that, even though an electricity shortage has seen widespread load-shedding, just one of the generators had its light on.

But then, as knock-off time approached, we finally saw something working. The road into Kusile is closed between 5pm and 6pm, including for coal trucks, when most of the plant’s 16 000 workers leave. There is no way in, only out, as both lanes are taken by the out-going traffic.