Could the fact that Eskom is already at ground zero suggest that the only way for the utility under Andre de Ruyters leadership is up, or is this hoping for too much? (Waldo Swiegers/Getty Images)

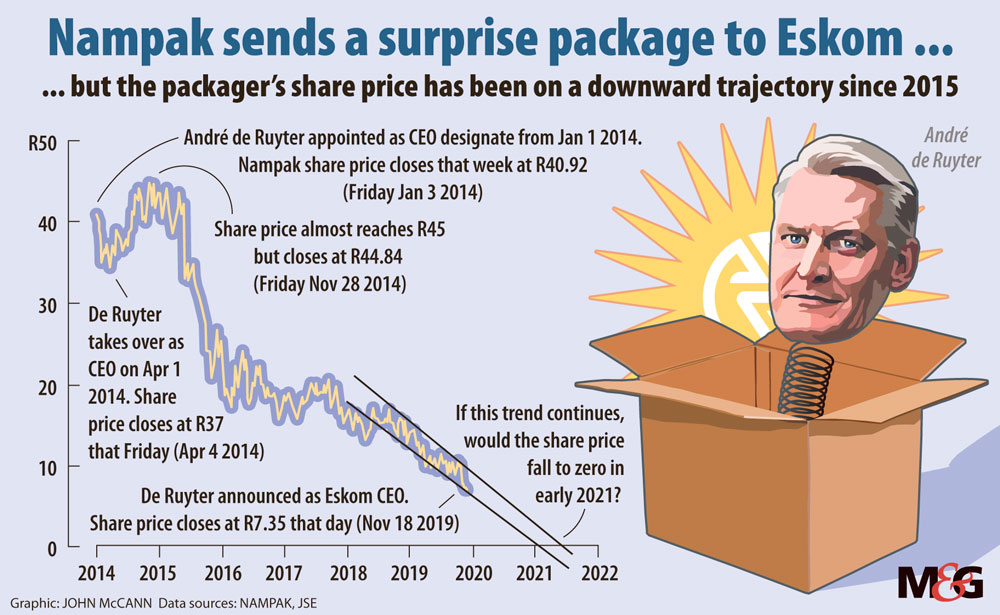

Run a straight line down the Nampak share price graph and you’ll find it hits zero as early as the end of next year. This is from a high in April 2014, when the packaging company was trading at R42 a share, having slumped by 80% to R7.40 this week.

This straight-line exercise has moment as Nampak’s chief executive, Andre de Ruyter, is named as the man to fix Eskom.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Most of Nampak’s problems — flat growth in South Africa and currency rationing in its key markets of Nigeria and Angola, which starved the company of much-needed funds to service debt — were created ahead of his arrival at that company.

This too is the case of his arrival at Eskom.

The power utility’s legion of problems are well and truly entrenched: what is needed is a turnaround artist, something which De Ruyter has patently not managed in his present gig.

But at least we are getting him cheaply? Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan said in a statement announcing De Ruyters’s appointment from January 15 2020, that he “would like to thank Mr de Ruyter for not only accepting this position at a difficult time for Eskom, but, given Eskom’s current financial situation, also agreeing to a lower compensation package than the position currently pays”.

The previous incumbent Phakamani Hadebe, who quit in July indicating that the job had been bad for his health, earned R6.8-million in 2018/2019. The pay cut may play well to Eskom’s wider constituency given that its bloated wage bill is seen as one of its key problems, but De Ruyter has not been leading by example on the pay front.

The Financial Mail reported in January this year that even though Nampak shareholders had not received a dividend for three years, and the share price was then less than one-third of what it was at the end of 2014, Nampak executives continued to be handsomely rewarded, De Ruyter pocketing R51-million in a three-year period.

Shareholder activist Theo Botha told the FM that executive incentives were kept high, despite the poor performance, by the remuneration committee, which lowered the targets used to calculate bonuses “in each of the last three years”.

Scroll back a few years before De Ruyter joined Nampak and we find him as a Sasol group executive championing the ambitious Lake Charles project in Louisiana to investors on April 9 2013 in New York.

“This is a unique opportunity for Sasol. It is, as [chief executive] David [Constable] said, an opportunity to spend three-quarters of our market capitalisation, significantly grow this business in a very short period of time and build up Sasol to a really higher level of performance both in terms of profitability and volume,” he said.

“But it also presents challenges. We don’t underestimate that spending this amount of money in a responsible way, making sure that we deliver value to shareholders is going to be a challenge. We are very well positioned both in terms of markets as well as our execution capability to meet these challenges in the right way.

“So first of all, let me draw your attention to the cracker, as I mentioned. That is 1.55-million tons, truly world scale. I think it is right there at the size limitation. However, we are not taking a scale of risk. We have taken a design that has already been executed, so essentially, an off-the-shelf design that we are going to take and implement. It’s been done before, so we are not taking undue scale at risk on that.

De Ruyter put the total capital cost of the project between $5-billion and $7-billion.

“The question is: How do we build this? And this is not a challenge that we take lightly, because if you look at megaprojects irrespective of where you are in the world, they are very challenging. And they typically have a history of cost overruns, of delays, of all sorts of challenges that crop up and eventually depress the IRR [internal rate of return] that you’re able to achieve on such a project.”

De Ruyter moved to Nampak the following year and so cannot be held responsible for the delays and huge cost overruns, which have plagued what is now a $13-billion project, the Sasol board at the end of October this year firing its joint chief executives Bongani Nqwababa and Stephen Cornell, and acknowledging that Lake Charles had tarnished the whole company.

I asked a colleague of De Ruyter’s who had worked with him at Sasol what his strengths are. “He knew coal contracts originally at Sasol, then ran gas development in Mozambique and chemicals overseas. A strategic procurement guy, a bargainer. Will sort out coal procurement, REIPP [renewable energy independent power producers] price excesses [and] corruption.”

Gordhan said that a holder of various qualifications, including an LLB and MBA, the Pretoria-born De Ruyter “is an accomplished chief executive with deep and wide experiences in creating and managing highly-performing businesses”.

“He spent more than 20 years with petrochemicals group Sasol in a number of senior management roles that gave him significant global exposure in the energy and chemicals industries. His portfolio included overseeing work in the US, Nigeria, Angola, Mozambique, Germany and China.”

Gordhan said De Ruyter will work with the Eskom board, management and the government to spearhead the re-organisation of Eskom, which includes its separation into three entities (generation, transmission and distribution) as well as the creation of Eskom Holdings.

“As things stand I am reassured that there is committed and capable leadership at Eskom in the chief financial officer (Calib Cassim) and the chief operating officer (Jan Oberholder), who, among others, have all been working tirelessly under the leadership of Jabu Mabuza over the past few months,” Gordhan said.

“I am confident that [De Ruyter] will lead a committed and capable management team that will work with him and the board to take Eskom forward.”

Nampak’s disappearing share value suggests that De Ruyter had, at best, a limited horizon at the packaging company. Could the fact that Eskom is already at ground zero suggest that the only way for the utility under De Ruyter’s leadership is up, or is this hoping for too much?