On the inside: Scenes of the courtroom

The voice that came to life was familiar, but different. It was Walter Sisulu speaking from the dock as a 52-year-old, not the grandfather who walked back into the world after 25 years in prison.

Sisulu’s words from the trial have become the focus of a celebrated French-made animation film.

The 16-minute film, Accused #2: Walter Sisulu, was made last year and has won a clutch of international awards already. It’s now being run at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg for the Reality Check exhibition this month and will continue to be shown until March.

“When I watched the VR film for the first time, I realised I had never heard Bram Fischer’s voice before and I was listening to Walter Sisulu as a much younger man for the first time, too,” says Apartheid Museum curator of exhibitions and education Emilia Potenza. The VR installation is a brilliant new technological hook for a younger generation especially, and makes real “an almost forgotten voice of the struggle”, she says.

“Sisulu didn’t have the charisma or the dashing good looks of Mandela. He was definitely more of the behind-the-scenes person, who left school at the age of 15 but was incredibly intelligent. He was the man George Bizos described as the ‘wise man of the struggle’,” says Potenza. The exhibition is about the “almost forgotten” person that Sisulu became as the world’s focus locked in on Nelson Mandela. Potenza says it was the way Sisulu (who died aged 90 in 2003) would have wanted it, understanding the importance of the different roles each person had to play in an evolving ANC. But she says a current-day gaze is fixated on looking for tension of egos and tugs of war over hierarchy in the party.

Reality Check is meant to be a pause, stopping long enough to ensure that remarkable individuals around Mandela, such as Sisulu, are not pushed to the margins. At the same time it’s a celebration of the museum’s first VR exhibition.

Accused #2 also holds the related story of how a piece of crucial South African history was saved from becoming part of our collective forgotten files.

In October 1963, as the Rivonia Trial started, only audio recordings of the proceedings inside the Palace of Justice in Pretoria were permitted. The recordings were done on dictabelts, a soft vinyl recording format, considered at the time as having a superior advantage for being tamper-proof as it couldn’t be cut and spliced. There are about 256 hours of recordings on about 600 dictabelt tapes. They survived in the custodianship of the national archives, but over the decades the tapes became increasingly inaccessible.

The machines to play back dictabelts fell into obsolescence, until eventually not a single one existed in South Africa. Only in 2012, through a partnership between the National Archives and Records Service of South Africa and the French National Audiovisual Institute (INA), did the process begin to adapt technology to make the recordings accessible.

It was the archeophone, an invention by French engineer Henri Chamoux, that made it possible to once again play the dictabelt tapes and, from this, for the recordings to be restored and digitised.

From this digitised archive, a team of French filmmakers imagined a feature-length film and went on to make The State Against Mandela and the Others last year. They followed this up with their virtual reality film about Sisulu.

Nicolas Champeaux co-directed the films with Gilles Porte and also curated Reality Check. For three years, between 2007 and 2010, Champeaux was bureau chief for Radio France International based in South Africa. He was the man who Chamoux contacted after listening to the recordings he was restoring.

‘Deeply moving’

Champeaux, Porte and producer Jérémy Pouilloux knew immediately that they had material for a feature-length documentary. Their film opened to international audiences, garnering huge acclaim. It is a mix of animation, interviews and original video footage from the time of the trial.

“We did many Q&A sessions with audiences after the feature film and even though we knew it already, it was Walter Sisulu’s testimony that many people found deeply moving.

“They said they saw and heard Sisulu fighting hard in court. He was very brave and he had composure, but they didn’t know Sisulu because they had only come to know of Mandela,” says Champeaux.

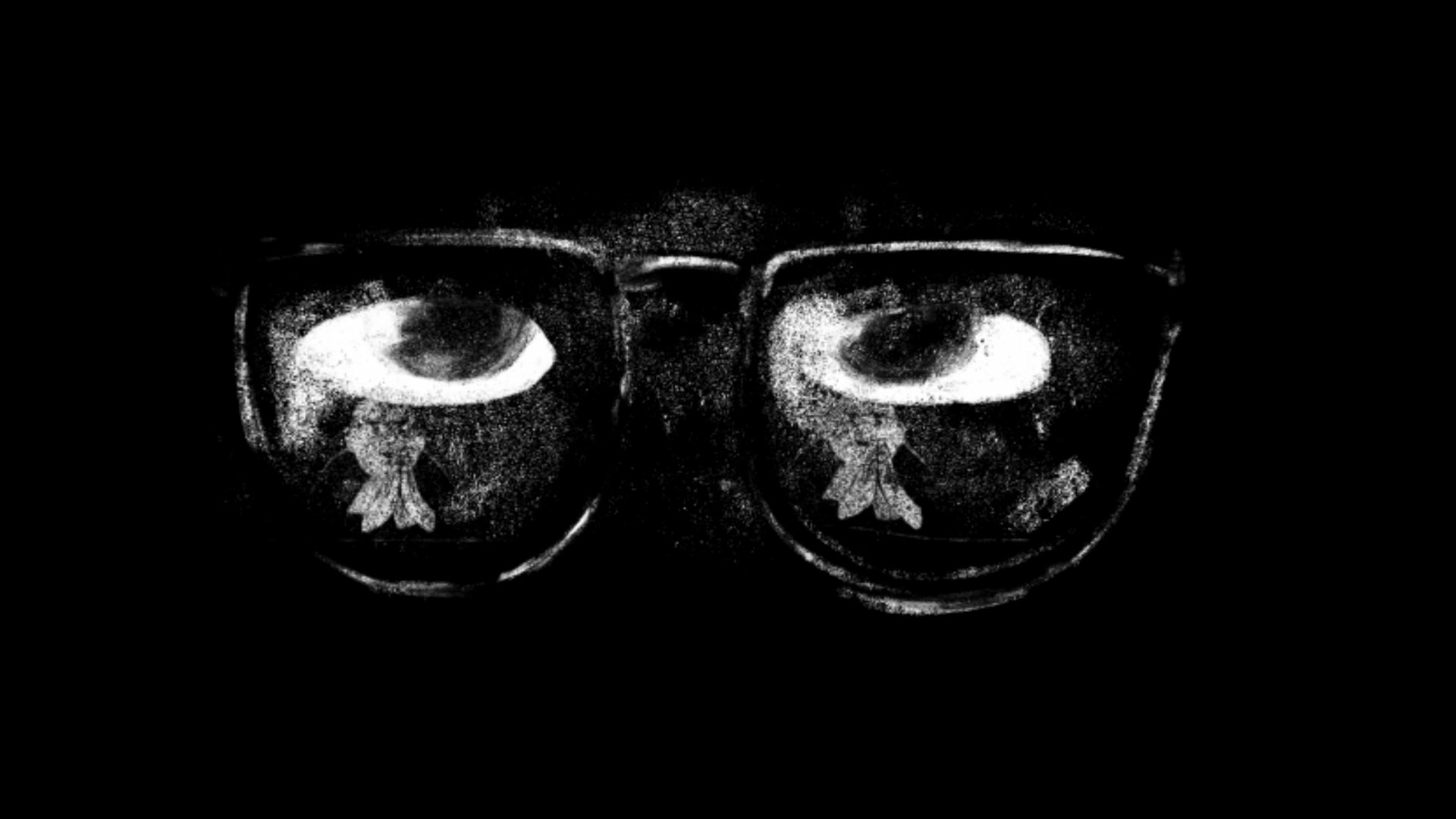

The VR animation exploits the 360° immersive technology. The drawings and animations were created by Dutch animation artist Oerd van Cuijlenborg. His charcoal and chalk drawings take the viewer into Judge Quartus de Wet’s courtroom, and music and 3D spatial audio complete the experience.

Black and white: Charcoal drawings by Dutch animation artist Oerd van Cuijlenborg, music and 3D spatial audio make the VR film Accused #2: Walter Sisulu a triumph

Champeaux adds: “We didn’t want the viewer to be distracted from the audio, but Oerd’s drawings match the vinyl’s crackles and his drawing style matches the texture of the film.

“It’s also in black and white, so you feel the suffocation and claustrophobia of the courtroom and understand what it must be like to be a black person in that courtroom in apartheid South Africa,” he says.

The film moves through Sisulu’s life while faithfully following the audio recordings. It includes his time as a miner, the night classes he took in the township and, of course, his testimony in the dock. It’s powerful to experience Sisulu’s life, sacrifice and determined strategy in an entirely fresh format.

“It has been very satisfying to watch audiences. I’ve never seen someone take off the mask, they remain captivated,” says Champeaux.

Accused #2 leads the way in a new direction for VR. It’s narrative-led immersive storytelling without a single dragon chasing you, or an assault of bright colours and noise, and you don’t have to fight off induced vertigo.

“The VR medium reinforces the emotions for the audience,” says Pouilloux. This platform coupled with “a story that resonates on a universal basis” has made Accused #2 a film that raises awareness of oppression and discrimination the world over, he says.

For Champeaux, Sisulu’s testimony is about saying no to injustice: “Maybe it helps others see how Sisulu fought back in the dock, even though he knew it would make his prison sentence harsher, maybe even bring him death.

“Maybe it makes us braver, even if it’s just to go to a protest march, sign a petition or to speak out”.

History being deleted

The Rivonia Trial reincarnated in VR is a triumph. At the same time, it highlights the crisis facing hundreds of other dictabelt tapes and archival footage that have not been digitised and are deteriorating every minute.

Heritage consultant Jo-Anne Duggan is a former director of the Archival Platform, a nongovernmental initiative to deepen democracy through the use of memory and archives as public resources.

She says the state of our national archives should be a national crisis.

“We don’t have the capacity or resources right now to keep digital records properly. Think of all the emails, WhatsApp messages, letters and photographs on phones that are not making it into record-keeping,” she says.

Duggan says non-paper based communications such as emails from Mandela’s early days in office are lost. The same for #FeesMustFall mobilisations that took place via WhatsApp group messages.

“We can’t recover information that is in a format we can’t read. We lose that history utterly,” she says, pointing out how information on stiffy disks and even DVDs already stands to be lost.

A scene from the virtual reality film where the artist draws attention to Sisulu’s glasses to take the view back to the trial.

Duggan says the value of records is not just for history, it’s also a way to hold politicians and authorities to account. “Records provide evidence to challenge impunity.”

Material record and memory are also linked: “Material record stimulates memory and memory evokes other memories to make another source of record,” says Duggan.

Records, ephemera and artefacts of our pasts are also deeply humanising, she says.

“Just think about hearing the voices from the Rivonia Trial. You hear the accents, you hear where maybe someone stumbled or how they pronounced a word. You hear that they are humans, just like us.

“If we want to understand the fuller story of the past, not just the narrative of big events, we need to understand the humanness of humans and this comes from proper record-keeping of our human story,” says Duggan.

This article was first published on New Frame.

An exhibition on Walter Sisulu, featuring Accused #2: Walter Sisulu, opened at the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg on 22 November and runs until the end of March 2020