Dancing Rose (2019). Oil on canvas 76 x 91 cm. (Raél Jero Salley/ Gallery Momo)

In War of Roses, Raél Jero Salley links seemingly unrelated, mundane moments together through the depiction of flowers. Whether in a garden, a bouquet in a vase, or in a print on the subjects’ clothes, flowers quietly sit in each of the artist’s paintings, almost unnoticed, witnessing the subjects’ stories unfold.

This is the artist’s second solo exhibition at Gallery Momo. The show has come to Johannesburg after its run at the gallery’s Cape Town quarters a few months ago.

Salley, who is from the United States, is a contemporary artist, teacher and an art scholar at doctorate level. His interest in oil on canvas lies in revisualising black experiences in a form that was historically white. After living in South Africa long enough to obtain permanent residency, his recent works have been in relation to the country’s sociopolitical landscape. His most recent body of work, War of Roses, painted in Cape Town between 2014 and 2019, is no different in its focus.

The exhibition’s title comes from the history of roses, which have been symbols of love, beauty, war and politics. As an example Salley points to the 15th century, a time when “the rose was used as a symbol for warring factions in the territory that becomes Europe.”

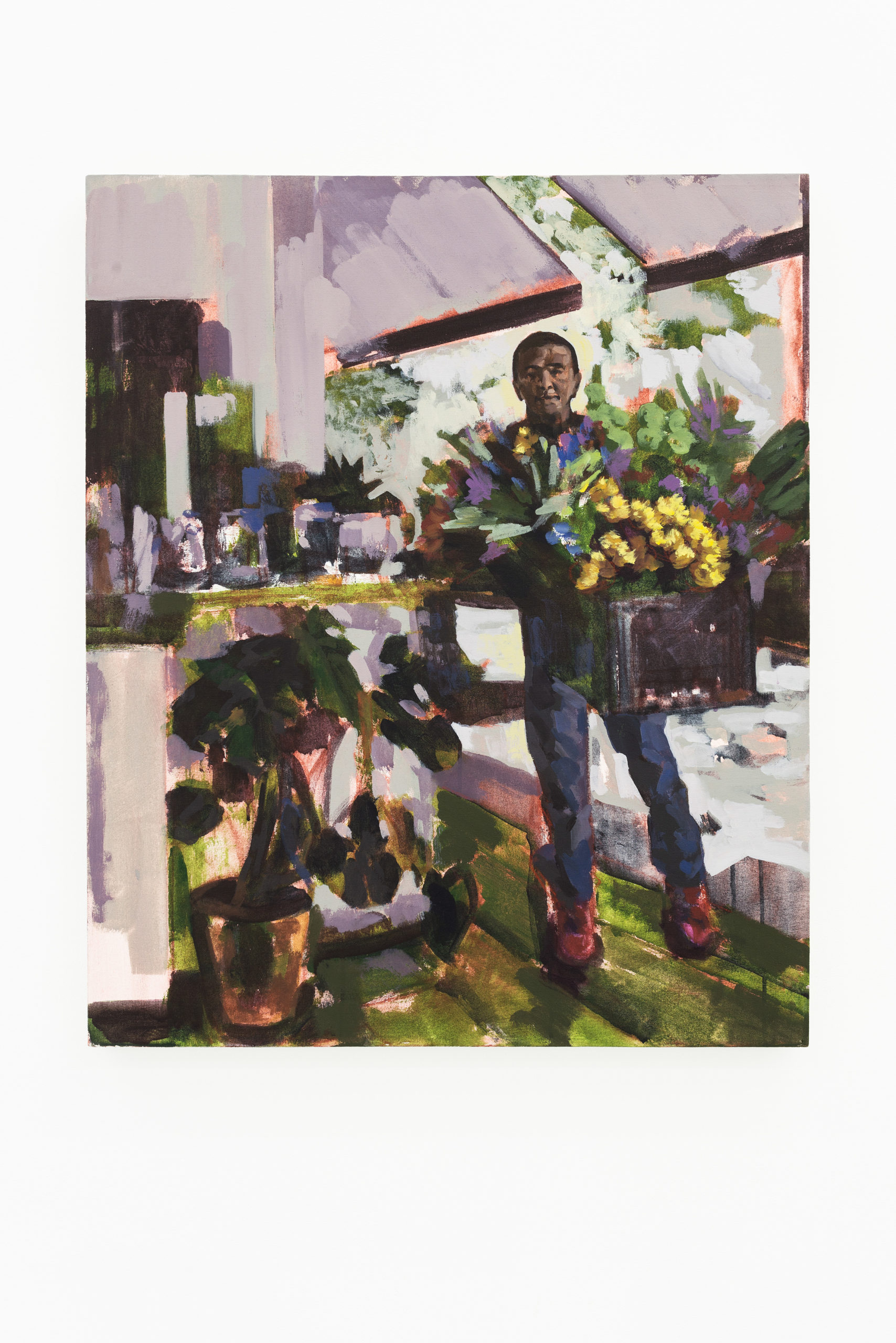

Flower Sale (2019) Oil on canvas 91 x 76 cm. (Raél Jero Salley/ Gallery Momo)

This concept is referred to as “botanical diplomacy”, and another proponent is Swiss artist c’s, whose ongoing body of work, Theatrum Botanicum, interrogates the idea. Using film, sound, installation and photography, Orlow touches on how one of the ways flowers have been used politically is through a “forced dichotomy between Western medicine and indigenous practice” as reported by the Mail & Guardian (“The art of naming things that already have names”, September 7 2018).

Speaking to the M&G, Orlow said he was struck by the fact that, despite South Africa’s 11 official languages, English and Latin are used to name plants in the botanical gardens. “It’s connected to the whole colonial history and it’s connected to all these other things that I had been looking at in the archives. It’s like a prehistory of that,” Orlow said.

Instead of expressing his sentiments about the poor sociopolitical circumstances, Salley’s work is more comfortable in defying notions that the black lived experience is devoid of joy by offering an alternative in which the black subjects are merry.

Salley can’t pin down the exact catalyst for this body of work but he recalls being moved by an archival photograph that kept return to his thoughts. “I got interested in the relationship and difference between the photo that I saw and my memory of that photo. At the same time, I got curious about the relationships within the photo,” he adds.

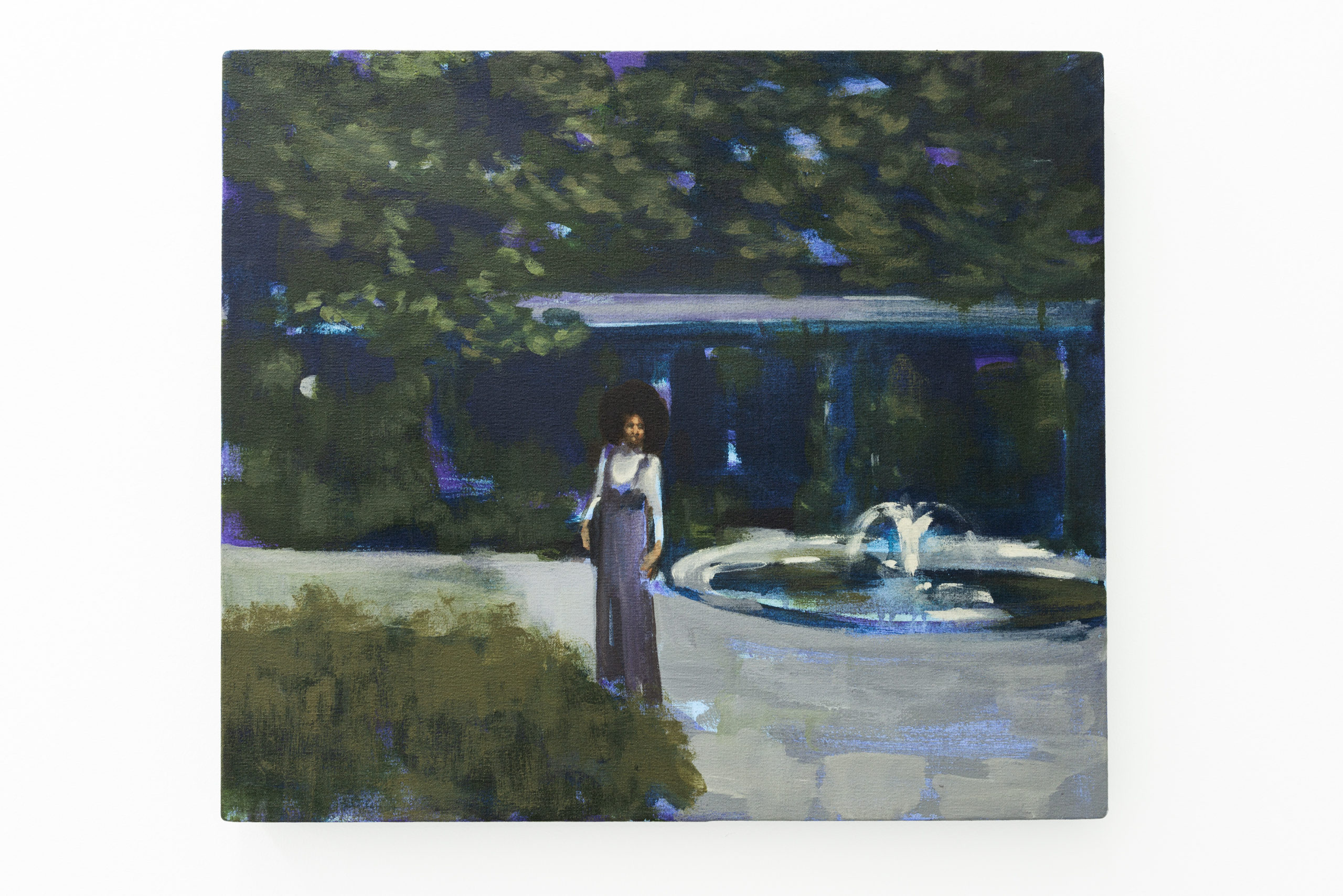

In Gloria (2017) a woman dressed in a white turtleneck and a long, shift dress makes her way through a lush garden. She wears her Afro in a halo that draws attention to her face. Even though we cannot make out her features, she appears to look straight at the viewer with a defiant, childlike calmness. Although she is dressed simply and carries on unbothered, her stance outshines the grand water feature and well-groomed landscape surrounding her.

Gloria (2017) Acrylic on canvas 63 x 54cm. (Raél Jero Salley/ Gallery Momo)

The flowers are an element that has to be sought to be seen: their role in the paintings alludes to the lived experiences of marginalised people. In capturing black people in celebratory mode, Salley positions the flowers in the background, almost as if to argue that invisibility is not synonymous with nonexistence.

Even though his depictions of the subjects’ surroundings play out in quiet hues of brown, grey, blue and black, the colours dance with one another to create a vibrant mood that’s raised by the occasional pop of white and pastel takes on yellow, peach and lavender on the subjects’ clothes.

Wild Orchids (2019) Oil on canvas 81 x 91 cm. (Raél Jero Salley/ Gallery Momo)

In addition to the narrative of Salley’s works, the show draws in the viewer through scale. Each painting’s scale varies, meaning engaging with Salley’s work is a dynamic experience. The reason he paints these somewhat peaceful, mundane scenes is to clarify “the difference between the good and the beautiful” that we easily ignore in our everyday lives.

The scenes in War of Roses play out in familiar settings such as bedrooms, public gardens, dance halls and alleyways. In a bid to expand their resonance, Salley’s depiction of subjects sees him softening their distinct facial features beyond recognition. The subjects’ haziness is reminiscent of the works of artists such as Karin Preller and Mashudu Nevhutalu. By obscuring them, this provides an opportunity for these representations to resonate with the viewer’s personal set of experiences.

At a time when contemporary art’s attention favours the risqué and outwardly confrontational, Salley’s focus on black people’s ability to exist joyously in spite of harsh circumstances is a safe but welcome approach.

War of Roses runs at Gallery Momo until December 13