Cultural production: Artist Judy Ann Seidman worked with the ANC-aligned Medu Art Ensemble in Botswana. (Delwyn Verasamy/ M&G)

If, for most people, the struggle disappeared with the “end” of apartheid, and the monikers “committed art” and “cultural work” today appear anachronistic, if not nostalgic, for artist, writer and activist Judy Ann Seidman, the plea for noncommittal art might sound absurd. Seidman’s retrospective, titled Drawn Lines, and showing at MuseumAfrica, is an exposition of her four-decade-long commitment to the prerogatives of cultural work.

The show contains Seidman’s earlier and later works in painting, drawing, print, dairies, sketchpads, pamphlets, paraphernalia, her unpublished papers and those of her comrades, as well as a photomontage depicting the artist’s collaboration with feminist collective, the One In Nine Campaign. A series of texts punctuates the walls, either as biographical or as historical detail, to better contextualise the exhibition. There are excerpts from texts written by Seidman and some citations culled from Amílcar Cabral, Samora Machel and Robin Kelley.

Considering the art convention in which Seidman has immersed herself — one that is sceptical of obscurity and insists on art’s didactical and pedagogic roles in society — her union of text and image unfolds as a strategic communicative imperative.

Seidman continues to associate herself and her work with socially engaged community struggles and organisations in ways art and artists now shy away from. Part of the anxiety around the notion of commitment (in the arts) has been its demand for open social and political engagement, which the post 1994 logic of cultural production has distanced itself from.

Drawn Lines invokes a double meaning of drawing as the prevalent medium of expression in the show, but also that of marking political demarcations [Judy Seidman]

The irony is that despite this noted incredulity towards commitment, art always inevitably finds itself committed in one way or another, and by virtue of its politically inculcated naivety, abiding by the laws of the (self-effacing) dominant system.

In the first instance, Drawn Lines invokes a double meaning of drawing as the prevalent medium of expression in the show, but also that of marking political demarcations.

The latter is obviously something difficult to commit to in South African public discourse, as any mention of lines or boundaries (largely from within national borders) easily slips into being about reversing our so-called constitutional gains.

The former, however — that is art as simply art — seems to be taken as a recreational endeavour that is skeptical of demarcations. This double bind is something artists and activists like Seidman continue to refuse, forcing, instead, continuities between art and politics. Dialectically, drawing lines is not simply about lines of separation (between people and power) but also of connection or solidarity within “the people”.

This kind of framing of art’s inherent political embeddedness has been crucial in disarticulating the dominant ideological flattening typical of the post-1994 cultural discourse that reproduces contrived notions of art and culture as politically disinterested. From this perspective, art is not a passive receiver and instrument but rather, as French philosopher Louis Althusser observed, “[W]hat art makes us see, and therefore gives to us in the form of ‘seeing,’ ‘perceiving’ and ‘feeling’ (which is not the form of knowing), is the ideology from which it is born, in which it bathes, from which it detaches itself as art, and to which it alludes.”

But how might we characterise or distil the ideal to which Seidman’s work expresses its commitment? Since age 11 Seidman has split her formative years between the US, where she was born and received her degrees in sociology and art, and Africa, where she practically grew up and experienced her political Damascus. As well as many critical essays, pamphlets and educational material, Seidman has also authored book-length texts like the instructional Red on Black: The Story of the South African Poster Movement (2007) and more recently an autobiography, Drawn Lines (2017).

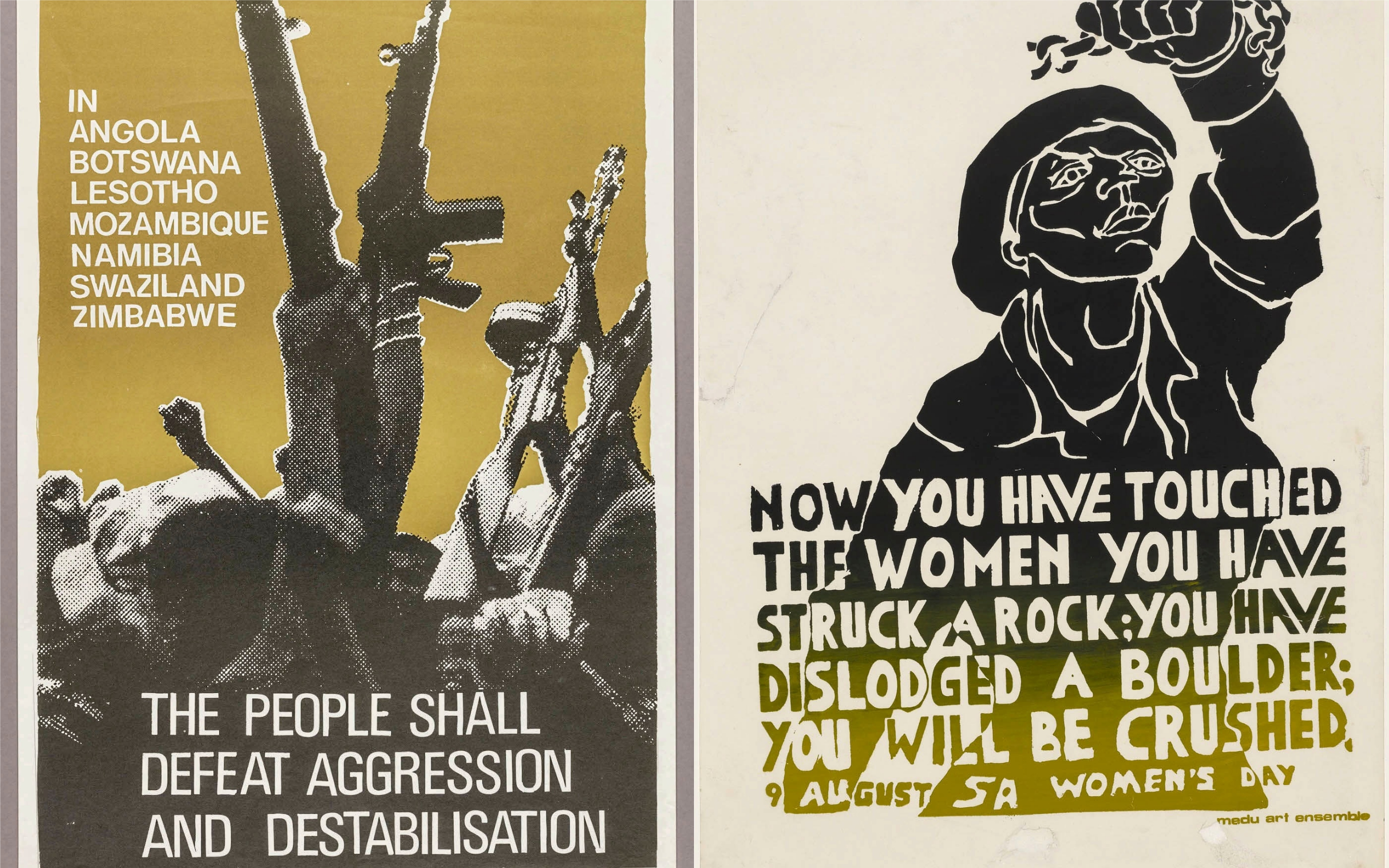

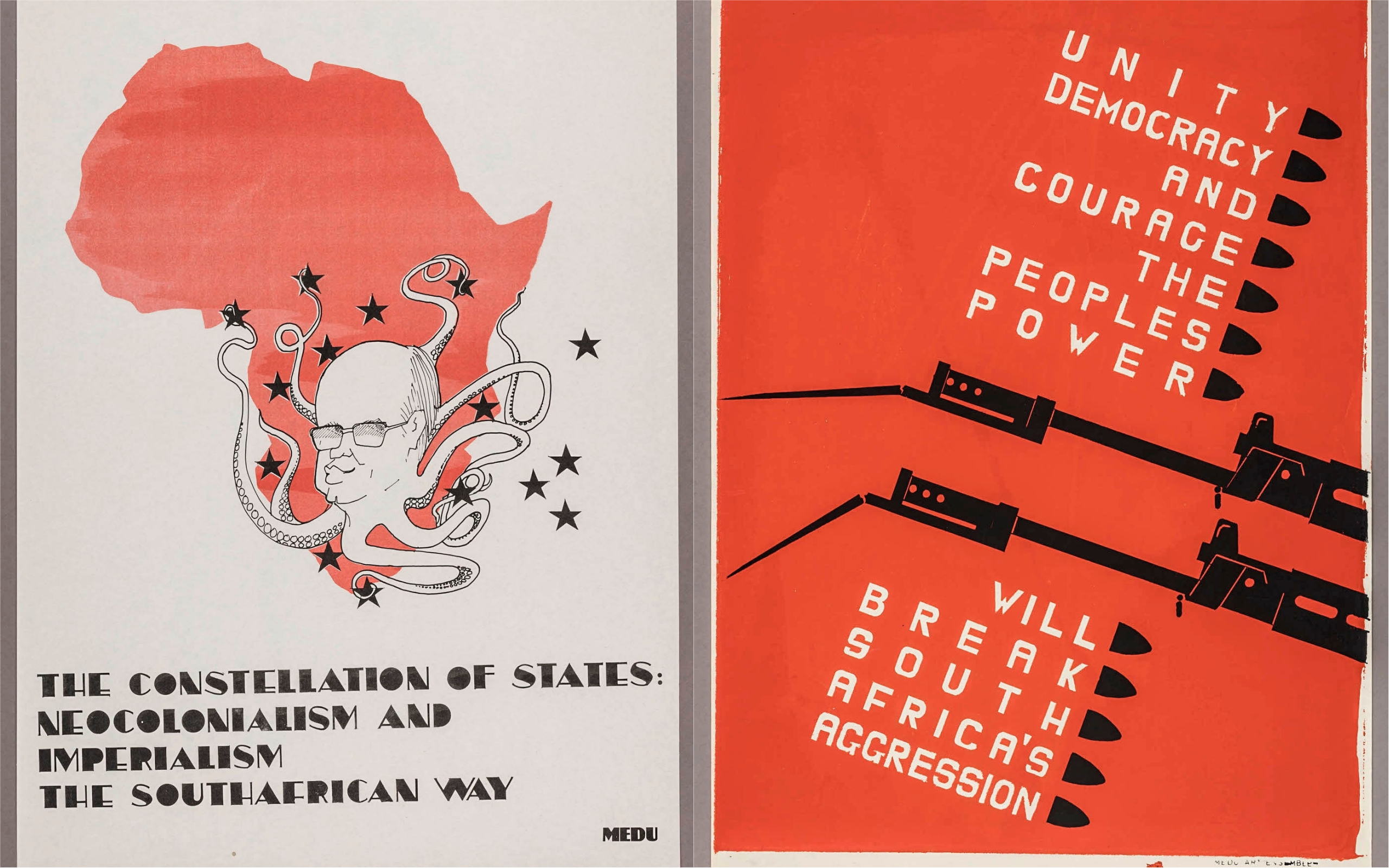

In 1980 she joined the ANC-aligned (so-called nonpartisan) nonracial artist collective, Medu Art Ensemble, in Gaborone, Botswana and started working closely with the likes of Thami Mnyele, Keorapetse Kgositsile and Wally Serote. Medu’s primary purpose was to educate and politicise the masses through culture: introducing workshops, art exhibitions, films, photography, theatre, dance productions, newsletters and posters to propagate the struggle for liberation. It fashioned a cultural production that was not just a socially engaged pedagogy, but one also predicated on the need to relate artistic labour to productive labour.

Medu was de facto distrustful of the superfluous exaltation in artistic auteurism, its abstraction and the individualist drive preferred by the art system. That three decades later, Seidman has mustered a serious collection of Medu’s political posters, writings and so on (exclusively belonging to the Judy Seidman private collection) remains an interesting political quandary, considering that this seems to contravene the very idea of collectivity.

This can, in part, be attributed to how the category of “work” instantiated by the notion of cultural worker — a moniker whose Marxian presupposition is often invoked unquestioningly — emerges out of a conceptual denunciation of race in leftist politics. As such, this blind spot towards race and racism abstracts the system into a colour-blind universal and, therefore, hides the complicity and ill contribution of the white left in the reproduction of antiblack racism. However, looking at Seidman’s show, the foregrounding of “work”-related themes turns what is essentially a demand to end colonialism into petitions for fairness 0n the factory floor.

Rarely would one boast about the aesthetic and formal pleasures received when looking at Seidman’s work, not only because her theme resists this but also because, at times, despite its insistence on the agency and life of working people, it appears almost lifeless. As a predominantly figurative body of work, the human figure and its speech become the fulcrum of whatever is addressed through and to it.

Although Seidman’s work undergoes a drastic change in the wake of her politicisation, one thing seems to be a perennial fixture: the preeminence of black people as subjects. From portraits to social scenes, and from worker strikes to armed struggle to toyi-toyis, this ubiquity at first glance appears to be a reversal of colonial landscape art that erased blacks from the pictorial plain, feeding into the myth of terre nullius. However, on closer scrutiny, this hypervisibility of black people in white artists’ works inversely reinforces a very particular scopic economy of colonial exoticism, typical among white mid-century artists.

Additionally, in her earliest works — seemingly devoted to figure drawing, a genre dedicated to the study of the human form and shape, often in stillness — black people are stationary models to be looked at. However, Seidman’s later political work devotes itself to a contrary effort, in which the human figure is constantly toiling and in motion, tossing her fist up or wielding a giant hammer.

Political awakening: Some of Judy Ann Seidman’s works on show at MuseumAfrica. Her earlier work was devoted to figure drawing, but her later political work dedicates itself to workerist iconographic scenes

The large body of work dedicated to workerist iconographic scenes, and thus the prevalence of the worker’s reality as the running theme, is indexical of the preeminence of class consciousness as an instantiation of commitment. It is a preeminence that places black people in service of the vaunted class struggle and not the other way around.

Yet, typical of this lens, the disjuncture between the figure of the worker as quintessentially black and the political claims that subtend nonracialism is rather too conspicuous to ignore. The category of the worker, as anti-apartheid activist and scholar Frank B Wilderson once argued, has been afflicted by a “conceptual anxiety” that makes thinking of white supremacy as the organising social structure impossible. Through the worker or even the poor, white supremacy appears denuded of historicity while, on the other hand, white people become default tutors to black people.

Perhaps one can read this worker vs thinker, or pupil vs master relation in how Seidman frames her collaboration with the feminist group, the One In Nine Campaign. The tension between the conspicuous presence of black bodies and absence of white ones, including hers, at the level of the image, raises interesting inquiries about “looking” as a position of power. Equally insidious is that, despite the artist’s acknowledgement of the collaboration, rarely do we hear these women speak, either through their own words or the sounds of their own voices, nor through fellow black female thinkers whose works have given explanatory power to black feminist presence. But they are on the walls, in their numbers, muted.

Although Drawn Lines is an appreciated instalment of Seidman’s lifelong work dedicated to a cause at an indifferent time, it’s equally important that we refuse to take theories of commitment only at face value. As much as political art and devotion remains anathema to the logic of contemporary South African art discourse, that dedication to traditions of protest need not occur at the expense of criticality.

Drawn Lines runs at MuseumAfrica until January 2020