Portrait of Malcolm X (Still from Who Killed Malcolm X)

In his intricately detailed historical biography, titled Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, the late historian Manning Marable argues that “a convergence of interests between law enforcement, national security institutions and the Nation of Islam (NOI) undoubtedly made Malcolm X’s murder easier to carry out”.

He characterises the web of FBI and Boss (the New York police department’s bureau of special services) surveillance that had formed around the NOI and Malcolm X’s two new groups following his split with the Nation as a “rat’s nest of conflicting loyalties”. High-ranking members of the NOI — such as national secretary John Ali and minister of the fervent Newark mosque, James Shabazz — were believed by several sources to have been police and FBI informants.

Activist and historian Abdur-Rahman Muhammad (who contributed some of his own long-running research to Marable’s 2011 book), is the driving force behind the Netflix documentary Who Killed Malcolm X?, co-directed by Rachel Dretzin and Phil Bertelsen. In the film the FBI’s counterintelligence programme strategy that precipitated Malcolm X’s murder is described as facilitating for “the NOI doing for the FBI what the FBI could not do for itself”.

Paroled from prison in 1952 after serving time for theft and housebreaking, Malcolm X (a prison convert to the NOI) rose up the organisation’s ranks quite quickly, becoming its national spokesperson and minister of the Harlem mosque in New York. A fiercely intellectual and charismatic autodidact, he grew the membership of the organisation at least tenfold (into the hundreds of thousands) in a relatively short time, quickly earning the supreme favour of the movement’s leader, Elijah Muhammad.

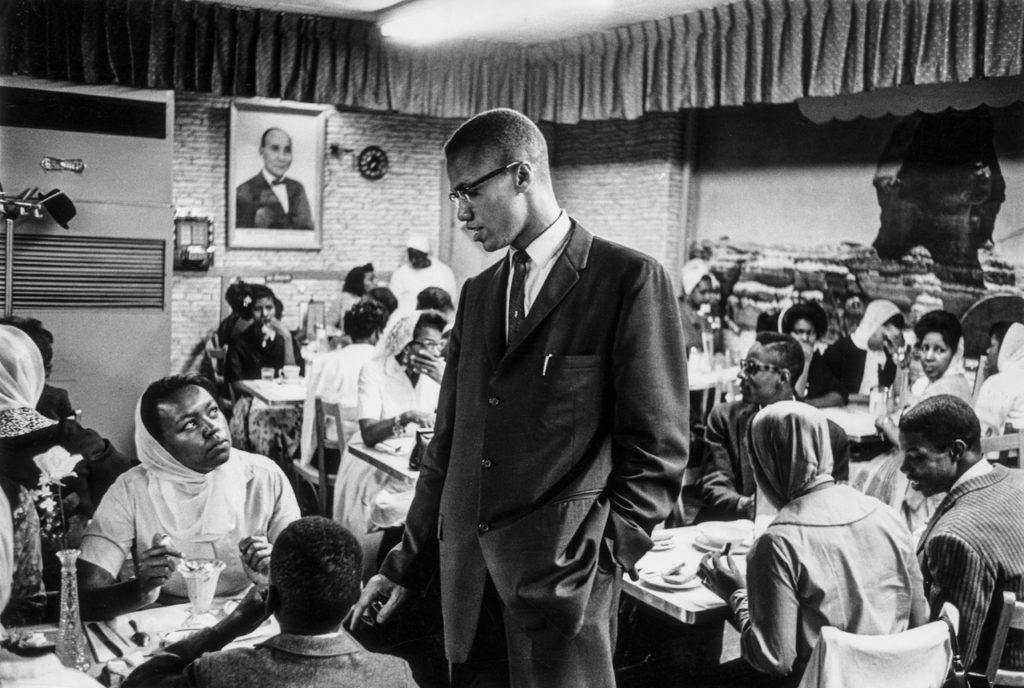

Malcolm talks to a woman inside a black Muslim restaurant in Harlem. (Richard Saunders/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Malcolm talks to a woman inside a black Muslim restaurant in Harlem. (Richard Saunders/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Muhammad was, by contrast, a retiring, sickly figure with a halting manner of speech. With Malcolm’s public profile rising higher than even that of Muhammad’s, and the prospect of the ageing mentor’s death always present, Malcolm drew the increasing ire of Muhammad’s children and the organisation’s inner circle. They feared that he could disrupt the workings of the money-printing machine the Nation had become should he usurp the top post.

Meanwhile, the US power structure’s fear of the proverbial “black messiah” reached a tipping point as the civil rights movement gained momentum in the 1960s and the FBI’s J Edgar Hoover lit a fuse under his men. He implored them to neutralise both the NOI’s and Malcolm’s momentum through ramped-up surveillance and the strategic trafficking of intelligence between the parties to heighten frictions. A series of public spats followed. These reached a decisive point when Malcolm likens the death of JF Kennedy to a case of “the chickens coming home to roost”, prompting Muhammad to suspend him — first for 90 days and later, as the acrimony built, indefinitely.

By February 21 1965, the time Malcolm X is gunned down by a hit squad from the NOI’s “Mecca” — its pivotal Newark mosque — so total is the infiltration of his new movements (the Muslim Mosque Inc and the Organization of Afro-American Unity) that his chief bodyguard (who administers mouth to mouth to him on the day) is a Boss agent.

The leader stands outside his bombed home before his death in February 1965. (Chris Bialkowski, STF/AFP/Getty Images)

The leader stands outside his bombed home before his death in February 1965. (Chris Bialkowski, STF/AFP/Getty Images)

The enduring lie trafficked by law enforcement forces about Malcolm’s death is that he was killed by a trio of men, two of them members of his former Harlem mosque. But from the evidence pieced together by Abdur-Rahman Muhammad and, indeed, the independent scholarship of other historians, we learn that the FBI’s records on Malcolm X’s death were identical to the version that was offered by the only apprehended gunman on the day, Talmadge Hayer (now Mujahid Abdul Halim), who always believed in the innocence of his co-accused. He eventually publicly stated this in an affidavit in 1977, two years after the demise of Elijah Muhammad and the change in dynamics that this event brought with it.

A still from the documentary, showing Talmadge Hayer (left) and Norman 3X Butler (right), one of the falsely accused

A still from the documentary, showing Talmadge Hayer (left) and Norman 3X Butler (right), one of the falsely accused

The film’s directors told the New York Times that their interest in the story was “the notion that the likely shotgun assassin of Malcolm X [the man who delivered the fatal bullet] was living in plain sight in Newark, and that many people knew of his involvement and that he was uninvestigated, unprosecuted, unquestioned”.

And so for the cameras, Abdur-Rahman pursues “shotgun dude” (Al-Mustafa Shabazz, known then as William Bradley), setting up the expectation for a confrontation where he wants to ask him: “Why did you do that? Why did you do that to our people?”

This pursuit of “shotgun dude”, aside from what it promises to bring to the table in the form of narrative and visual spectacle (which turns out to be many shots of Abdur-Rahman striding across the screen carrying his laptop bag over his shoulders, re-enacting his research path) never really delivers.

Granted, it is hard to keep a viewer interested in endless, consecutive frames of stylised highlights from redacted FBI files, so Abdur-Rahman had to hit the tarmac. The trips to “Mecca” in which Abdur-Rahman interviews several current and erstwhile members of the Newark fold, tell us that the people connected by the “convergence of interests” Marable writes about always knew the depth of these connections and the weight of culpability resting on each node. So, as Rahman plays to the camera, all he is doing is revealing what many viewers may already know — that the streets, the precincts and the US power structure the police serve, always knew the reasons why Malcolm had to go.

Abdur-Rahman’s proximity to the black Muslim community and his relative insider status deliver him to the door of interesting, seemingly off-the-cuff remarks. As he “zeroes in” on Shabazz (who dies before this happens), Abdur-Rahman stops by a group of Muslims in Newark, where he again raises the question outside a mosque, to the effect of, “What are we going to do about that, uhm, William Bradley?”

The response from activist Zayid Muhammad is, “Leave him alone, leave him alone, leave him alone, because he’s probably being protected by the state. If he did what they did and he’s out here like that, they’re protecting him … I don’t want you going to jail over this on some bullshit.”

There are several of these encounters in the film that, although perhaps colouring our understanding of how Malcolm was perceived by his own immediate community, at the end of it, represent a misdirection and a lost opportunity.

By the end, after all the minutiae about Malcolm X’s last year and his last day have been exhausted, one still feels as if there has not been enough panning over the bigger picture and the exact nature of the state’s involvement in instrumentalising the triggermen.

Through no fault of the filmmakers’ per se — except in these critical lapses of emphasis — after watching the film, one is reminded of the state’s abiding contempt for the life of Malcolm X, and the lives of the falsely accused (such as Muhammad Abdul Aziz, known then as Norman 3X Butler). It is a contempt best evinced by the Manhattan district attorney’s seemingly glib decision to reopen the murder investigation 55 years after the fact, knowing that it is a case of more of the same or, at the very least, too little, too late.