Despite the media's wish for a neat story, the African continent's response to Covid-19 is all over the map

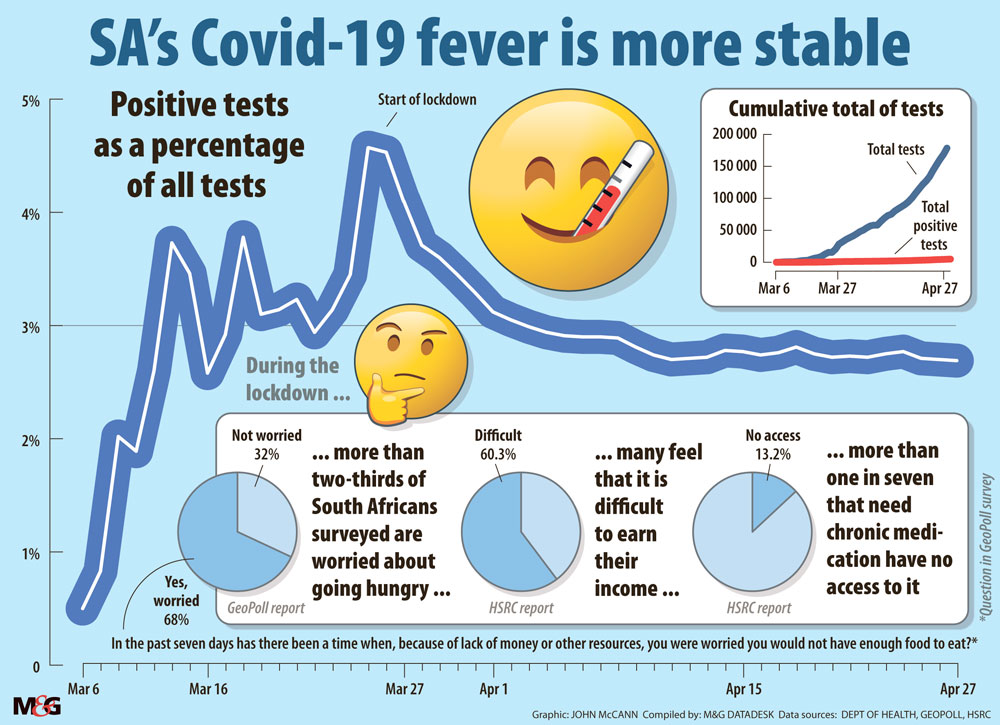

After a five-week lockdown, the country has been able to screen six million people and conducted close to 200000 tests for Covid-19. Almost 5000 people have contracted the disease, with more than 1200 testing positive in the past week. The health department has said that when the weekly rate is under 100 positive cases it would show that the pandemic is coming under control.

In his speeches to the nation, President Cyril Ramaphosa has said the six-week lockdown has saved “tens of thousands” of lives. Last week, he announced a R500-billion stimulus package but the economic cost of the lockdown has meant millions of people have lost part, or all, of their basic income.

On Friday, the regulations ease slightly when country moves from level 5 to level 4 lockdown, but restrictions on travel remain firmly in place.

Shabir Madhi, a director at the South African Medical Research Council and professor of vaccinology at the University of Witwatersrand, said the virus could be with us for a few years. “We must be clear. This is not a three- to six-month project. This is not the 2020 phenomenon. This pandemic will be with us until the end of 2022 at the earliest.”

Madhi, who has researched the trends of viruses, argues that the only way to control the rate of transmission of the virus is for there to be herd immunity. This would be when two-thirds of the population has had Covid-19 so they can no longer be infected. The focus would then be on looking after people susceptible to the worst of the disease, in particular those with comorbidities.

He said the expectation is that this year between 25% and 50% of people in the country will be “infected with this current wave in South Africa”. After this there will probably be a waning of the virus. “Then a few months later — which no one can predict — we are going to get another wave of the pandemic and this will repeat itself a few times until a significant percentage of the population has got adequate immunity to sort of interrupt the rate at which the virus is infecting people.”

Doctor Anja Smith, a health economist at Percept, said at this time it would be very difficult to talk about exact time frames of when we will be dealing with the virus.

“Though I fully acknowledge that the virus could be with us for a very long time, where it could flare up like the seasonal flu, there are strides being made in scientific innovation.

For instance, there are a number of universities and laboratories that are experimenting with a vaccine. One such team is in Oxford and they are talking about September this year. These important strides could decide how long we have to live under such conditions,” she said.

The government has said its goal is to ensure the transmission rate — how many people an infected person infects — drops to below one. This will stop a flood of cases that could overwhelm the healthcare system, as has been the case in places such as Italy and New York.

But the lockdown, which seeks to drop the transmission rate, is coming at a huge human cost.

A survey conducted at the end of last month by the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) shows that just under a quarter (24%) of respondents had no money to buy food. More than half (55%) of the respondents who live in informal settlements, and about two-thirds of respondents living in townships had no money for food.

More than 60% of the respondents said they are worried that they won’t be able to pay their bills. This is from a sample of about 20000 people who participated in an online survey.

International market research company GeoPoll conducted a similar, but smaller, study in sub-Saharan Africa. Their findings are similar to those of the HSRC.

Its regional director, Ricardo Lopes, said that although many people were concerned about catching the virus they were more worried that starvation would kill them sooner.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

“In terms of South Africa, about 50% of respondents are actually fearful of contracting the disease. This ranks quite high, but the fear of the economic impact is only 2% lower. And that’s ultimately what we are seeing in countries where a hard lockdown has been implemented.”

GeoPoll surveyed 4 788 people in 12 countries and found that the younger the respondents were the more they worried that they would not have enough food. The older the respondents were the less worried they were about having enough money to ensure they had food.

788 people in 12 countries and found that the younger the respondents were the more they worried that they would not have enough food. The older the respondents were the less worried they were about having enough money to ensure they had food.

The HSRC research showed that more than 50% of those surveyed believed the Covid-19 lockdown would make it difficult to keep their jobs and feed their families. And 40% said the lockdown would make it difficult to keep their jobs.

Alana Potter, a lawyer at the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa, said that although the HSRC survey had about 20000 respondents the majority of them are people who have the time and the means to answer the questionnaire. This suggests the survey did not include the most vulnerable people.

“Every one of our clients has expressed a real concern around food security. The HSRC findings were 25% [of people who had no money to buy food] of their sample, which was about 20000 people. Can you imagine the real number of people who are worried about what they will eat?” said Potter.

She added that the biggest concerns as measures to flatten the curve continue are food security, water and sanitation and tenure security. “Social relief and economic support are the only way that lockdown can continue in any sustained fashion without utterly destroying the very fragile livelihoods that people have made for themselves.”

Help, she said, would probably come in the form of food vouchers that could replace the current emergency rollout of food parcels. “This voucher system has to be urgently rolled out. These are critical issues that can decide if South Africa maintains a lockdown in some form.”

Health Minister Zweli Mkhize said on Tuesday that the Eastern Cape has 616 confirmed cases of Covid-19. The Mail & Guardian reported that Mkhize has sent a team to assist with the tracing, screening and testing.

Francis Leonard Mpotte Hyera, the head of the Walter Sisulu University’s department of public health in the faculty of health sciences, said the situation in some areas in the Eastern Cape is dire. “There aren’t efficient strategies to reach grassroots communities and train them to deal with the pandemic. In communities in villages across this province, for instance, people don’t have access to the right information.”

He said that when he was driving from Mthatha to East London “people were going on as business as usual. I went to a certain shop and I put on my mask. I was asked why. I told them I was protecting myself and others from the virus and a young woman, maybe in her twenties, lambasted me for insinuating there was Covid-19 in the shop.”

He attributed the rise in the number of cases to limited information available. “We cannot say if the lockdown has worked or not. But we can say that the message has not really reached our people sufficiently.”

Some findings from two surveys

Human Sciences Research Council

- Cigarettes (12%) are more accessible than alcohol (3%) during the lockdown. A quarter of people from informal settlements said they were able to buy cigarettes.

- The majority of people said they had not had any involvement with law enforcement, while 15% of respondents said they were treated badly or roughly.

- 13% of people reported that their chronic medication was inaccessible, with more than 20% of them living in informal settlements and rural areas.

Geo-Poll

- 78% of the respondents said businesses were providing a hand sanitiser.

- Television was the source of information for 72% of respondents.

- 67% of the respondents said that when they were worried about whether they would have enough to eat they switched to cheaper brands. — Athandiwe Saba