Global influences: Soldiers back up police at Madala Hostel in Alexandra to get people to comply with Covid-19 rules. (Photo: Luca Sola/AFP)

COMMENT

South Africa has never had a good government in any of its four phases of history. Romantic ideas about the first of these phases, life prior to the arrival or outside the influence of émigrés from Europe, are skewed. There had been no Garden of Eden or natural state of harmony in Southern Africa that can somehow now be returned.

The subsequent colonial era was no high bloom of development and internationalisation: the British concentration camps from 1900 onwards provide the harshest example of this. These camps set the scene for the most condemned of the brutalities of the previous century. The cruelties, pain and humiliations of the apartheid half-century from 1948 onwards are in our living memory. The harm done during the post-apartheid quarter of a century since 1994: the devastation caused by HIV denialism, corruption during the presidency of Jacob Zuma and the incessant crime.

And now, Covid-19.

The massacres

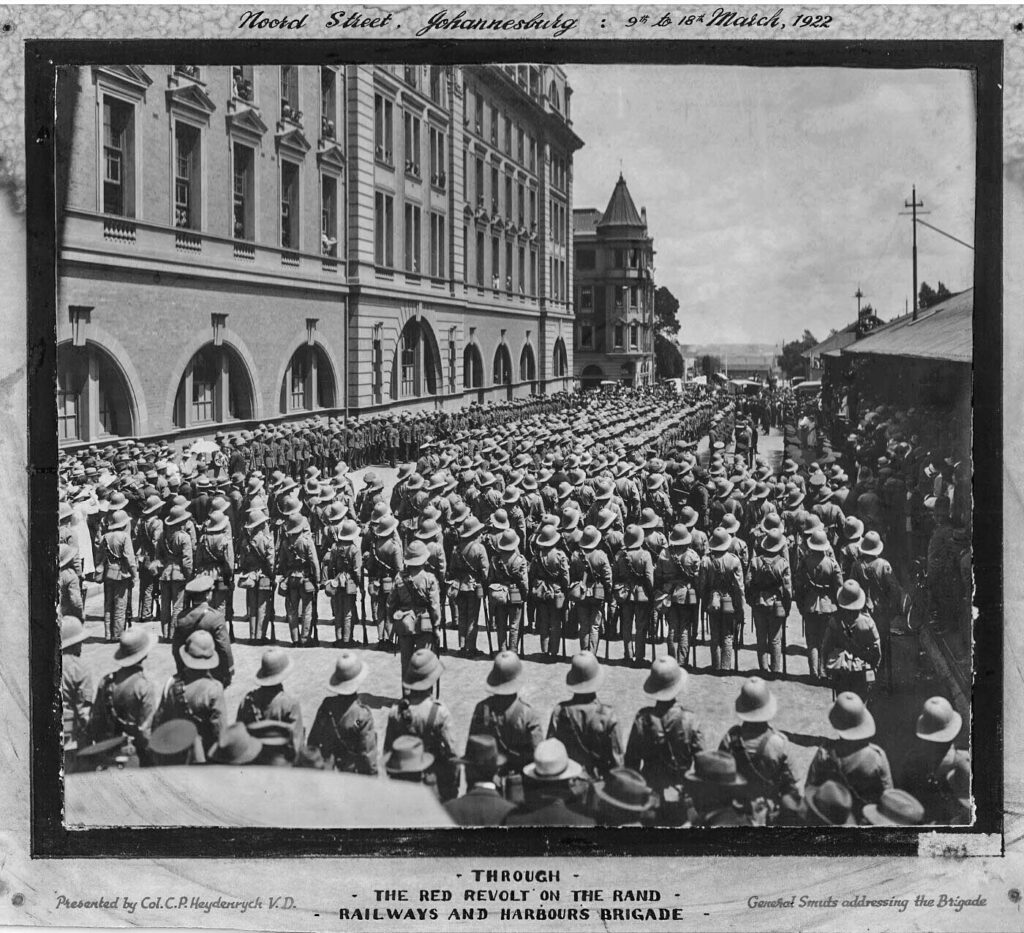

Each era had its massacres — just one example committed by each ruling elite are: the Difaqane/Mfecane (1820s), the Rand Rebellion (1922), Sharpeville (1960) and Marikana (2012). Each of these massacres shows the heartlessness that had accompanied rule in South Africa.

Economies were shattered by World War I. White gold miners went on strike and Prime Minister Jan Smuts lost the 1924 election to a coalition of the National Party and Labour Party after soldiers crushed the 1922 Rand Revolt.

Economies were shattered by World War I. White gold miners went on strike and Prime Minister Jan Smuts lost the 1924 election to a coalition of the National Party and Labour Party after soldiers crushed the 1922 Rand Revolt.

We have been failed by successive governments, individually, as groups and as a whole. South Africa has never had a good government.

In each of these phases the general populace experienced the negative effects of these vices of state, but has never had the wherewithal to bring about change. Rather, by quirks of history, world-changing events have been part of the key impulses for changing the political paradigm. European colonialist expansion brought to an unanticipated end versions of tribal rule in the region. World War II set the stage for the unexpected 1948 change of government in South Africa. The end of the Cold War brought down the last bastion of the apartheid regime, its anti-communist stance. 1994 ensued.

In each case a host of factors worked to constitute anew the political dynamics in South Africa.

And now we have “the virus”.

The virus crisis

It has been amply pointed out how Covid-19 has brought to the fore the most negative of the impulses of South Africa’s ruling party. Though the motives may be lofty, the practices are the opposite. Ignoring basic human rights, downplaying murder by the state security apparatus, either gross errors in presentation of fact or lies along with monopolising the spread of information, playing party politics where livelihoods are at risk, the inability to rid us of leaders who have lost moral authority — this is all-round bad leadership. We deserve better.

Commentators have indicated the Stalinist impulses of senior figures in leadership positions as they deal with society during this virus crisis. Analysts have shown the lunacy of economic policies that do not take seriously the harsh choices we have to make — by keeping to an even harsher ideology. For these abuses of power, we and future generations will pay dearly.

In the same way as it has been argued that South Africa had seen in apartheid the last vestiges of colonialist rule, we have seen in post-apartheid South Africa the last vestiges of communist rule. Communism’s international legacy includes 80-million deaths in the previous century. We do not accept apologists for apartheid or Nazism. Why do we not do the same with the last vestiges of communism?

It is time to call this government to an end. “The virus” has served us with the vital global circumstance to bring about a new political paradigm.

The branding of communist policies, so deeply infecting the current government, as “progressive” is sleight-of-hand deceit. There is nothing “progressive” to infantile economics. Nor to pretending to serve justice to the poor, while bullying everyone into impoverished servanthood. We must dismiss such ideologues to the furthest fringes of our democratic society.

Let us rather choose something that is alive and present to the sensibilities of our country.

Post-Covid South Africa

What is the kind of society in which we want to live? Let us be concrete. For a fair, good society:

We want to choose our representatives to make the country work well — as a whole and in its presently dismal municipalities. So, democracy stays. (And neither consulting nor party appointments constitute democracy; voting for responsible, responsive individuals does.)

We want to be protected from abuse of power by these chosen representatives and the organs of state (such as the police and armed services), and by any other figures or groups with influence in society. So, constitutionality and the rule of law stays, and more so than at present.

We want to live as freely as possible from crime. Laws and law enforcement must be improved.

We want a free, open, easy economy. The more businesses thrive, the more society thrives. (No, this is not a call for old-style capitalism in which people are fodder for industry. Rather, the exact opposite, of mutual care between employees and employers. With good social safety nets, which reflexively bounce back into labour all those who can work.)

A small, efficient state service is a must. Small, clever government serves its people; bloated officialdom serves itself. State-owned enterprises should be merely enterprises. State administration, including taxation, must be simplified.

The branches of government (legislative, executive, judicial) must function with independence, and in open interaction with broader society. The additional estates of the mass media, civil society and more are to function as treasured aspects of a healthy society. An effective opposition in Parliament and offices that protect democracy such as that of the public protector, must be valued.

High quality education takes central place, without yet another ideologically-enforced approach with its muddying terminology that diverts education from teaching and learning. This starts before school-going age, and continues post-schooling in diverse educational institutions, with life-long learning highly prized.

In expressing a continued commitment to “!ke e: /xarra //ke”, “Diverse People Unite”, diversity invites cohesion. Rather than an ideologically-formed single version of diversity, which is the opposite of freedom, a diversity of diversities should characterise society as we strive to live together well.

Whom shall we send?

Whom shall we choose to give expression to these qualities? None of the political parties offer us good choices. Something different is required; perhaps something akin to government by chosen professionals. The golden standard behind this kind of thinking is: public service. Not power or some other seduction, but finding meaning in life by making one’s world better — that ought to be the prime motivation for those in key political positions.

That brings to mind a figure such as the former public protector, Thuli Madonsela. Her credentials and reputation are impeccable. She does not want to be in politics. That would make her a good president. Minister of finance? Perhaps Tito Mboweni, for much the same reasons.

In general, the political leadership should be well-qualified, experienced and well-regarded in their field to be considered for a cabinet position. The same on other levels of government too.

We want specialists because we want success. Grandiose ideologues and comradeship networks create disaster. All should be can-do pragmatists, making do with the limitations of our country by drawing on our strengths.

Responsibility, be it by a minister or a municipal official, should include that they must use the public services in their care — the health minister goes to public hospital.

Wellbeing and care

In these and similar ways, we can build a society that is not stumbling towards disaster. Rather, we become a region with healthy buffers. Life brings hardship, no doubt, some which will always be unforeseeable. Differently to now, with an able society and a political leadership awake to wellbeing and care as core goals (rather than the self-serving power games), we can have the resources to handle these hardships in a non-destructive way.

We live in a spring tide: the seas are rough. That requires high levels of energy to alter our political landscape. Spring also means a new season. And of that South Africa is in dire political need.

Christo Lombaard is research professor at Unisa. He holds doctorates in communication studies and theology

Global influences: Soldiers (above) back up police at Madala Hostel in Alexandra to get people to comply with Covid-19 rules. Photo (top): Luca Sola/AFP