(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

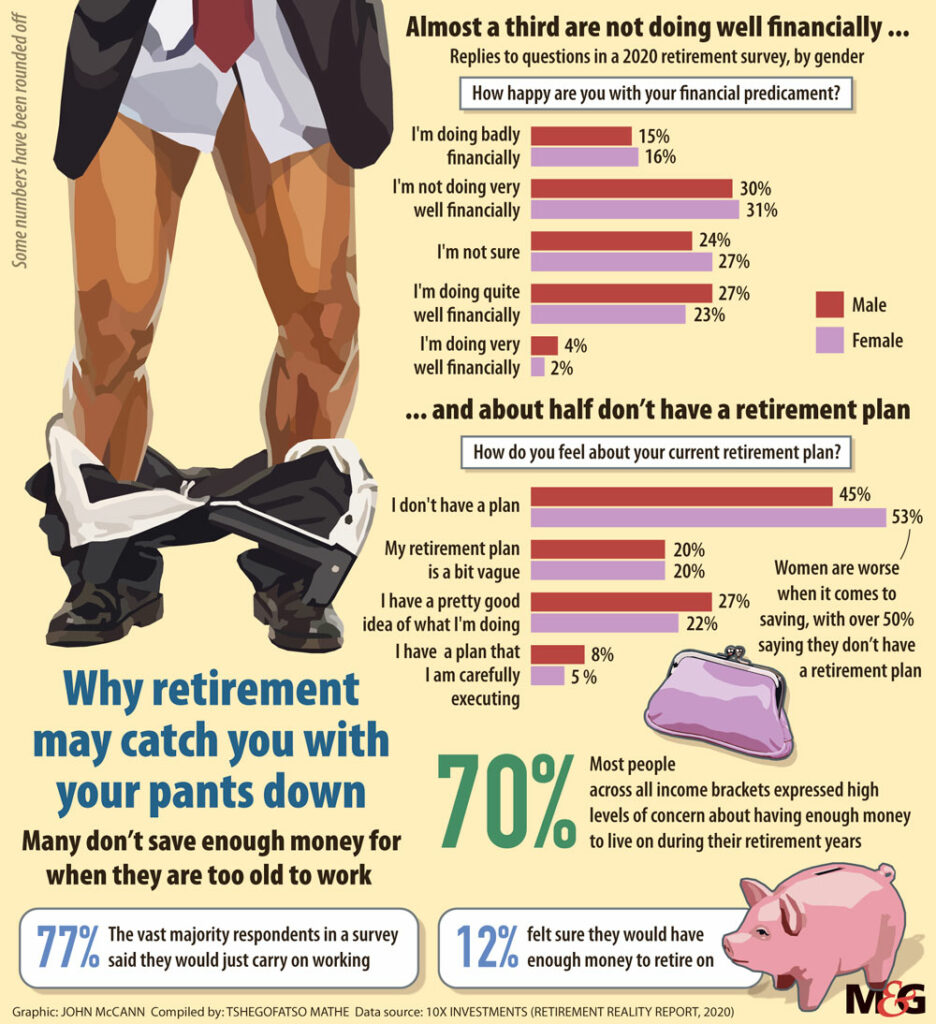

As many as 50% of South Africans don’t have a retirement plan — and low-income earners can’t afford one. And only 6% of respondents said they had a retirement plan they had properly thought through, according to 10X Investments’ Retirement Reality Report of 2020.

This is in line with the treasury’s estimates that 6% of people will have a decent retirement. The findings are based on a 2020 Brand Atlas Survey, which looked at the lifestyles of 15.1-million economically active people with a monthly income of more than R8 000.

Chris Eddy, the head of investments at 10X Investments, said people cannot save without a minimum income level. The company’s report also showed that people in the low, medium and high income brackets are equally worried about having enough to retire on.

The Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (Saldru) found that 50% of South Africans are chronically poor; 20% are middle class; 4% are rich; 11% are the transient poor and 15% the vulnerable middle class. The vulnerable middle class has about R5 300 a month and the middle class about R25 500. The poor have less than R800 a month and R560 is below the poverty line, according to Statista.

Thomas Ledwaba*, a 33-year-old software developer in Johannesburg has three retirement savings plans, which he believes will have accumulated millions by the time he retires at the age of 65, allowing him to live comfortably.

He has been working for 12 years, and he learned about retirement savings when his employer placed a portion of his income in a provident fund. Ledwaba took out two other saving plans — a retirement fund with Sanlam and a retirement annuity with Old Mutual bank.

He says he is putting all this money away because he learned early on that it’s important to save to successfully manage the uncertainties that come with life.

Ledwaba’s story is commendable, but it’s not a common narrative among South Africans.

No money for savings

More than 55% of respondents in the 10X Investments survey said they do not have enough money at the end of the month to save.

The survey result show that 53% of women don’t have a retirement plan, up from 51% last year. Women constitute 51.1% of the total population and on average live longer than men.

They save less because they don’t have enough money to do otherwise; they draw on their savings and choose to put money in the bank instead of investing it, according to 10X Investments survey.

Dhashni Naidoo, FNB’s consumer education programme manager, said that improved financial literacy would result in a greater understanding of retirement savings.

She added that better financial planning, which involves readjusting budgets and spending habits to make provision for saving — and discipline and perseverance to stick to the savings plan — was a way to combat part of the retirement problem.

With the expanded definition of the unemployment rate (which includes people who have stopped looking for work) at 42% and the economy in tatters, exacerbated by the pandemic, many South Africans’ concerns are about having enough money for daily living.

Alex Cook, the chief executive at financial planning and investment group GCI Wealth, said some saving vehicles can be expensive for low-end earners. He said the cheaper mechanisms such as unit trust have high distributing costs.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

High fees

The retirement report also highlights this, saying that high fees are a contributing factor to South Africa’s retirement crisis. Seemingly small regular charges against savings compound to leave a large hole in people’s pensions. The report showed, for instance, that in the context of a consistent 40-year savings regime, someone paying 3% in fees rather than, say, 1% a year, receives almost 50% less money when they retire.

A report by BankservAfrica, released in March this year, said that about one million people out of the estimated 5.3-million over the age of 60 have private pensions.

The government’s older person’s grant of R1 860 to R1 880 goes to 3.655-million people, many of whom have no other source of income.

Cook said if more people could save, this would free up government spending on grants and enable it to improve services for the public.

Regarding how much people need to save for retirement depends on what a person’s retirement goals are, said Naidoo. If someone wants to travel when they have retired, they will need more money than someone who wants to stay at home.

Naidoo said the older person’s grant will not necessarily help maintain a person’s standard of living during retirement. So, reliance this grant is something people shouldn’t aim for. Rather, for those who can afford to save for retirement and those currently employed, they should be actively saving in an appropriate retirement plan.”

The earlier people start saving for retirement the better, she advised.

* A pseudonym

Tshegofatso Mathe is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the M&G