More than 250 000 tonnes of wheat have been lying in containers at the Durban and Richards Bay ports for about a month after the South African Revenue Services (Sars) withdrew the European Union free duty quota for local millers.

More than 250 000 tonnes of wheat have been lying in containers at the Durban and Richards Bay ports for about a month after the South African Revenue Services (Sars) withdrew the European Union free duty quota for local millers.

On 11 February, grain importers were elated to see that Sars had gazetted the duty-free quota. But the next day, the revenue service recalled it without giving any reasons.

A private email from millers to other grain importers, which the Mail & Guardian has seen, shows the level of confusion the retraction caused.

The email read: “Sars retracted the first notice published on the 11th February 2021 with ambiguous reasons that the notice, which was published, was actually not published and traders, therefore, could not have qualified for a preferential quota rate. As a result, it ordered traders to cancel the declarations made following the notice, which it had since removed from the web.”

According to the email, Sars also said that if millers did not cancel their orders, there would be consequences.

The quota forms part of the economic partnership agreement between the European Union and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) countries — Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa. It came into effect in 2016.

The EU guarantees Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, Namibia, and Eswatini 100% duty free access to its market. It also fully or partially removes customs duties on 98.7% of South African imports.

Sam Legare, of the department of agriculture, land reform and rural development, said that for SACU countries, the agreement allows several products to be imported from the EU through the tariff-rate quota system. Some of the products are imported duty-free, while some are at a reduced import tariff.

In the case of wheat, about 300 000 tons is imported from the EU and it’s shared among SACU countries. South Africa gets 251 495 tons of the total.

Sars and the department of trade and industry administer this process on a first-come, first-serve basis, but in this instance, there was a lag.

The two departments did not respond to the Mail & Guardian’s questions about the delay. Instead, on Tuesday, 2 March, after numerous requests for comment, Sars published the gazette, effective from the next day.

The millers said that in attempts to resolve the problem, letters were sent to Trade and Industry Minister Ebrahim Patel and Deputy Finance Minister David Masondo. Some of the local importing traders also tried the legal route, but were not successful.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

One miller, who wanted to remain anonymous, said the wheat reached South Africa’s shores on 9 February, but, because of the delay, millers had to either wait or import the duty free wheat at a tariff of R102.60 a tonne.

Some importers paid the tariffs to ensure they didn’t run out of wheat. Others could not.

The millers said everyone complied with Sars’s request to cancel products cleared on duty-free.

This week, before Sars gazetted the quota, the millers said that 251 4950 tons of wheat were at the ports, and some had been loaded and cleared out. This relieved space constraints the ports.

The wheat was ordered late last year for delivery in February.

The miller said the gazetting and withdrawal of the duty-free quota implied the “government is collecting duties on tonnes and millers must pay and will have to pass it [the cost] on to consumers”.

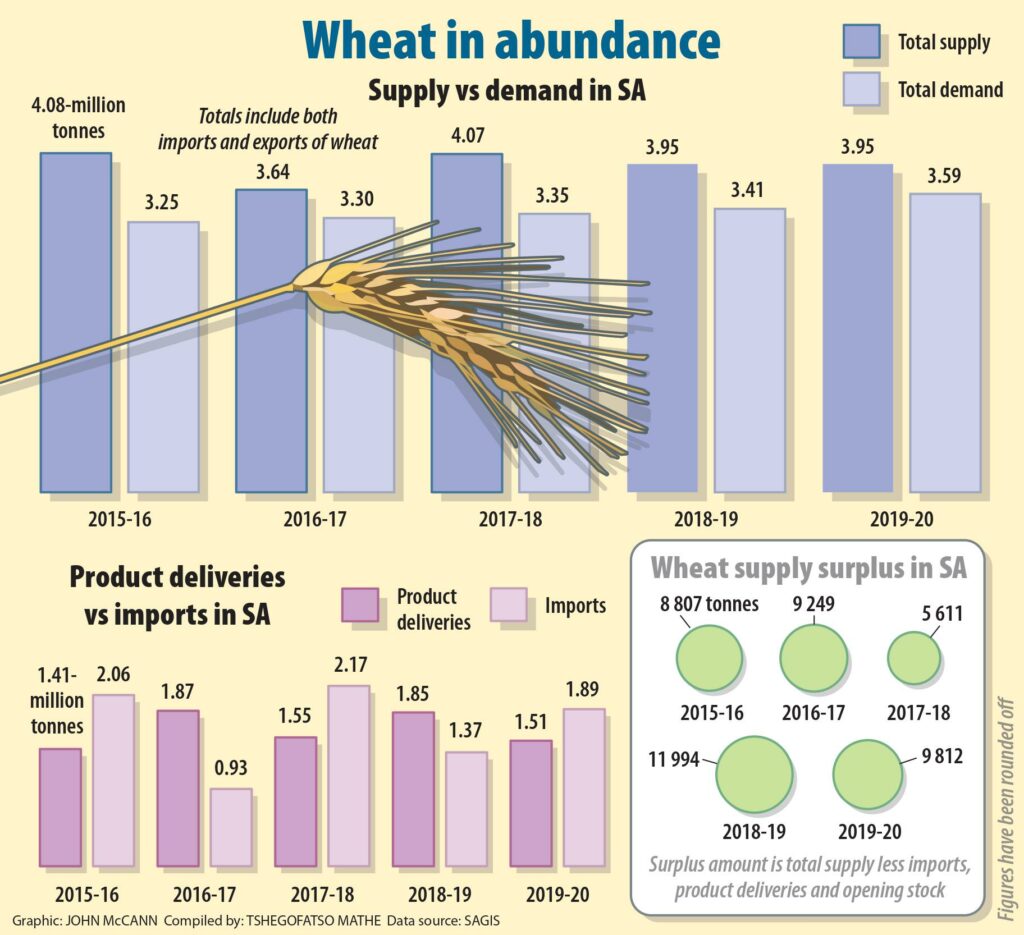

Ruan Schutte, an agricultural economist at Grain SA, said South Africa is a net importer of wheat.

The country produces roughly 50% of the amount of wheat needed and the balance is imported from countries such as Canada, the Czech Republic and Germany.

Trudi Hartzenberg, the executive director at the Trade Law Centre said that in recent years, there were instances where local exporters did not use all the quotas which the trade agreement provides for. “So we have missed out on those duty-free exports to the EU countries, which is such a pity.

“One wonders why did we not use them. Is it difficult to meet the standards requirements?”

She said the EU imposes stringent standards on specific agricultural products and if traders do not meet them, they cannot export.

Although reasons for the lag were not given, Hartzenberg said that any trade delays have consequences. Not only for the companies but the value chain, which will negatively affect the consumer.