Repositioned: Lesetja Kganyago, the governor of the South African Reserve Bank, says transformation is about more than demographics; it’s about culture and strategy. Photo: Simon Dawson/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Earlier this week, the governor of the South African Reserve Bank, Lesetja Kganyago, joined parents to protest against the lack of transformation at his daughter’s school, Cornwall Hill College.

But in an interview with the Mail & Guardian on Wednesday Kganyago was all business. He discussed South Africa’s post-Covid recovery, restoring its credit ratings and criticism that the bank’s monetary policy is outdated.

“Today I am talking as the governor, so I won’t be bringing the school work into the workspace,” he said.

The reserve bank, which first opened its doors on 30 June 1921, celebrates its centenary this month. For the majority of those 100 years the reserve bank, charged with safeguarding the country’s financial stability, was predominantly white.

“I am the 10th governor in 100 years. Until the appointment of Tito Mboweni in 1999, all the governors prior were white males … I am the second black person in 100 years to become governor of this institution.”

‘A decent job’

Demographically, the reserve bank has come a long way, the governor said.

“But transformation is more than just about demographics. It’s about culture. And it’s about strategy. Building on what the 1999 executive team had done, we managed to strategically reposition the South African Reserve Bank in pursuit of its constitutional mandate and made it an institution that is focused on policy strategy,” said Kganyago. “That is fundamental. Because that repositioning of the organisation to focus on policy strategy didn’t go unnoticed.”

Kganyago’s leadership of the bank during a period of political and economic turbulence has garnered him acclaim from many quarters. In 2018, he was named central bank governor of the year.

It is this reputation, and the 15 years he spent at the treasury, which has caused some to speculate that Kganyago could be in line to take over as finance minister, should Mboweni be reshuffled.

But, as he has said in the past, Kganyago is a technocrat, not a politician.

“I have served the people of South Africa to the best of my ability using my technical skills.

“I do not think that I have got particular political skills that I could bring to the treasury job … I believe that I am doing a decent job here. And that is how I would like to continue serving South Africa.”

Recovery

When the Covid-induced economic crisis hit, the reserve bank responded by cutting the repurchase rate by 300 basis points in 2020. This aggressive policy approach drove interest rates to historic lows.

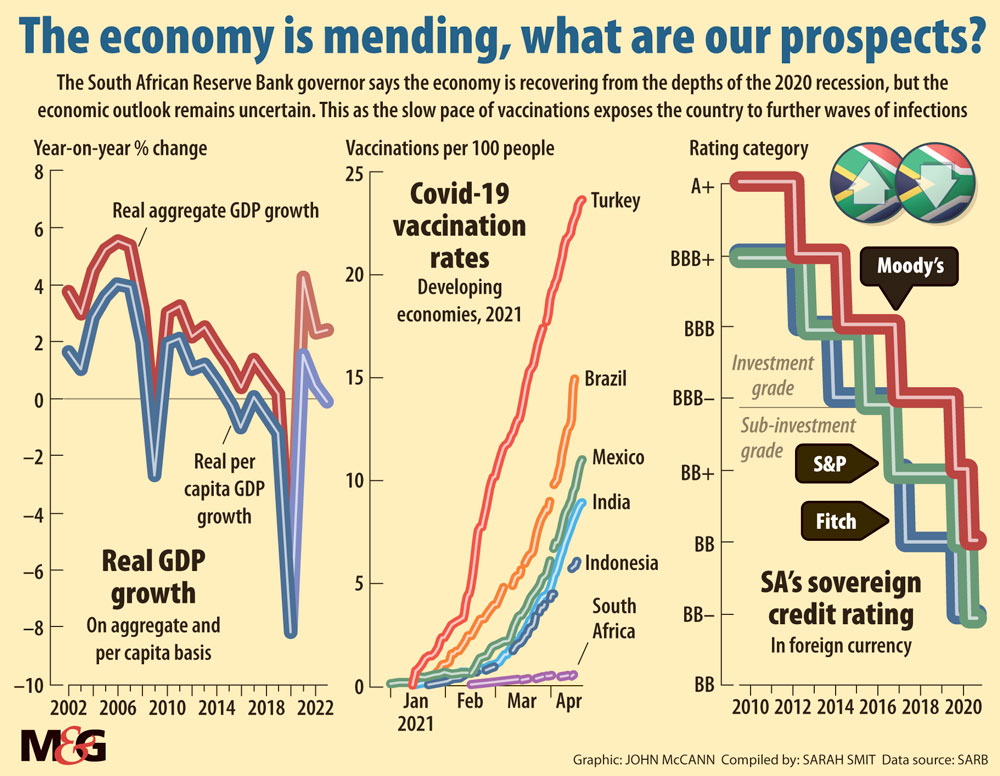

The reserve bank has forecast that economic growth will reach pre-pandemic levels in 2023. But even then, South Africa’s economy will probably still be in the doldrums.

The recent jobs statistics, which showed that the country’s unemployment rate has reached a record high of 32.6%, signal the severity of South Africa’s growth crisis.

[related_posts_sc article_id=”416960″]

“If an economy is not growing, it can’t create jobs,” Kganyago said. “The economy is recovering, but it is still below the level it was in December 2019 … So let’s be clear, the reason why unemployment is rising is because the economy was weak. And while it was weak, it was hit by this extraordinary shock. This big bounce that we are expecting this year will still not take us to where we were in 2019.”

Last week, ratings agencies Fitch and S&P Global maintained South Africa’s credit score at three notches below investment grade. Fitch noted that the economy will be supported by the rise in commodity prices, but tight public finances and electricity shortages will hold back growth. A slow vaccine roll-out will also dampen growth.

Addressing South Africa’s struggle to restore its creditworthiness, Kganyago said: “Our credit rating has nothing to do with the rating agencies. Our credit rating has to do with our behaviour as a country.”

To restore the country’s rating to investment grade, the state has to look at where it has gone wrong and correct those wrongs, he added.

“We have got to get growth going. We have got to alleviate all those constraints to growth: energy shortages, poor transport infrastructure. We have got to restore our public finances and arrest the debt trajectory. We have got to restore the credibility of our institutions that were gutted.”

Trade-offs

Covid-19’s economic assault raised questions about the design of fiscal and monetary policy, and how they may better support economic recovery. Kganyago would not comment on criticism of the treasury’s fiscal consolidation efforts.

“You know, on the 16th of May 2011, I walked out of the treasury to go and start at the reserve bank,” he said, explaining his decision to keep out of debates on fiscal policy.

“It was a very interesting journey, because on 31 July 1996, I walked from the reserve bank to collect my letter of appointment from the treasury. And on 1 August 1996, I was in a lift club with my former colleagues at the reserve bank. We parked at the reserve bank and I walked to the treasury. As I walked to the treasury, I knew it was the last time I could say anything about monetary policy. On the 16th of May 2011, as I walked to the reserve bank, I knew it was the last time about fiscal policy.”

Just as detractors have criticised the government’s economic recovery plan — which will be implemented amid efforts to rein in public spending — some have accused the reserve bank of not using its full arsenal to rescue the economy.

Proponents of modern monetary theory, which proposes that central banks can print money to finance governments, have called the reserve bank’s focus on interest rates and inflation targeting outdated.

Kganyago said modern monetary theory is akin to populism. “And you see, populists can say whatever they think people want to hear. They wouldn’t like to have difficult conversations. The nature of populism is that countries collapse under policies that are not sustainable. I think that modern monetary theory falls into that category.”

On accusations that the reserve bank is too conservative, Kganyago said: “If anything, our implementation of monetary theory is very modern. We are doing what most banks in the world are doing at the moment.”

As the reserve bank governor, Kganyago said he has no shortage of people giving him advice on what he could be doing better. “Besides the 2 000 good men and women in the reserve bank who give me advice, there are some 58-million South Africans who also offer advice.

“I have to process all of these things and formulate a view about what is the correct policy to adopt.”

Economics is a dismal science, the governor added. “The tragedy in South Africa is that people want to be involved in a debate on economic policy without having to provide robust evidence that can be tested. In economics we argue on the basis of evidence. You can’t just make a slogan, or meet in a crowded hall and say: ‘This is the policy we must adopt’.”

Kganyago said policymaking involves trade-offs. It is also about making decisions that will benefit the economy in the future. “What impact does it have on future generations — on our children and our children’s children? What we call intergenerational equity is about trade-offs.”

He quotes former finance minister Trevor Manuel, who said in a 2006 budget speech: “To govern is to choose.”

“You are going to have to make choices. And those choices are going to be difficult. And it doesn’t matter whether you are in the treasury, or you are in a central bank, or in any government department, there are trade-offs to be made.”