Infighting: Oil producer Saudi Arabia (oilfield pictured above) is opposing the United Arab Emirates’ wish to increase production far beyond agreed limits, fearing toppling prices. Photo: Simon Dawson/Bloomberg/Getty Images

A rift in a powerful oil cartel has put the global market off kilter — setting off fears that another price war may be on the horizon, just as the global economy recovers from a downturn induced by the Covid-19 pandemic.

On Monday a meeting of Opec+, an alliance consisting of the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) and non-Opec partners, was called off amid a reportedly bitter stand-off between Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

A new date for the meeting, which aims to reach a compromise over an output deal, has yet to be set.

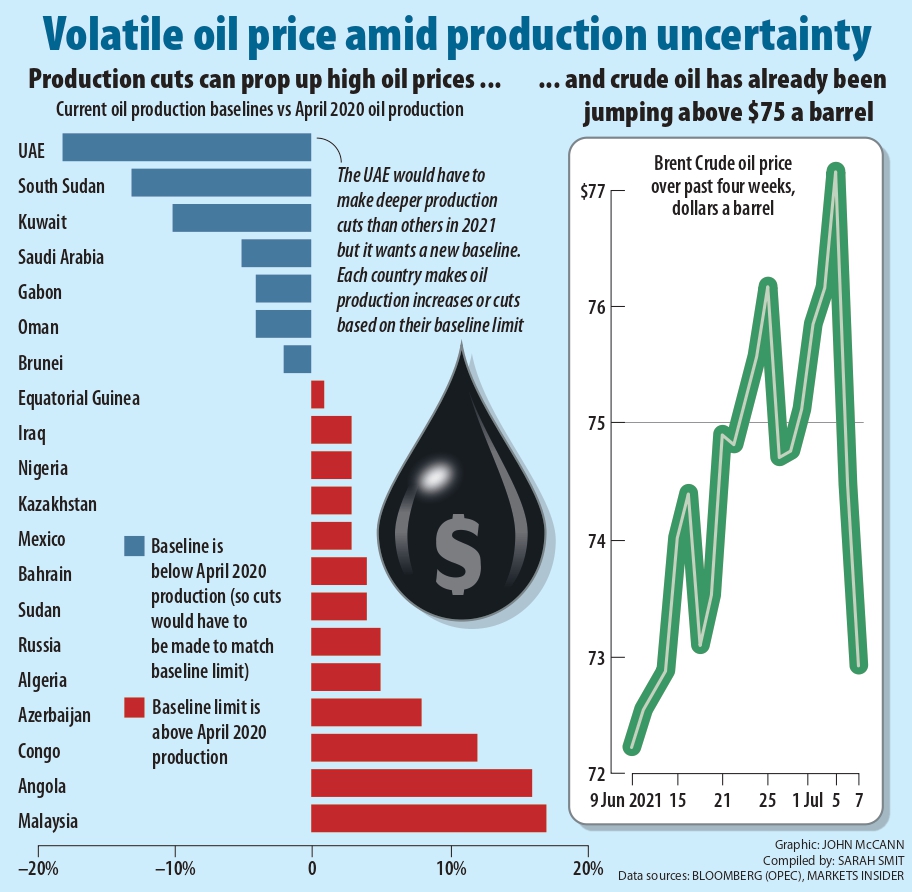

According to reports, at the heart of the stalemate is the UAE’s opposition to a decision to add 400 000 barrels to the oil output each day from August to December. The UAE has reportedly demanded a much higher production limit, taking this position after heavily investing in additional capacity.

Reports of infighting caused the price of Brent crude to spike on Monday, closing at above $77 a barrel. Failure to resolve the standoff would leave the existing Opec+ output deal in place, keeping almost six-million barrels a day off the market until April 2022 and setting off further price volatility.

The UAE’s demand could upend the fragile Opec+ alliance, which last year put an end to the Saudi-Russia oil price war that had caused prices to plummet. Like the current stand-off, that tussle was initiated by a breakdown in talks between key oil producers.

Russia reportedly rebuffed a proposed output deal that was devised to deal with Covid-19’s impact on global oil demand. The pandemic triggered an unprecedented slump in demand, the result of the blow to transportation and industrial fuels during lockdowns, as well as massive global oil market sell-offs.

In April 2020, the Opec+ alliance came together to bring balance, agreeing to cut oil production in order to reduce supply and rebalance prices. The baseline for the calculation of the adjustments was the output of October 2018, when the global oil market was last hit by a steep drop in prices. Russia and Saudi Arabia absorbed the brunt of the cuts, each agreeing to cut their production to 8.5-million barrels a day.

Striking a balance

The rebalancing efforts successfully stabilised the oil price and, as Covid-19’s effect on the global economy started to wane, demand began to recover. Prices rallied in the first half of 2021 and market optimism was bolstered by the Opec+ decision to gradually ease supply curbs by adding about two-million barrels a day from May to July.

In its June Oil Market Report, the International Energy Agency said the Opec+ alliance needed to open the taps to keep oil markets adequately supplied.

The pace of the recovery in demand has caused prices to skyrocket. In South Africa, although a stronger rand has kept rampant hikes mostly at bay, a weakening currency coupled with the current volatility in Opec+ could trigger steep increases in the petrol price.

Energy expert Boitumelo Sehlake said it was critical for Opec+ to maintain balance in the oil market “because if we can’t get that balance, we will end up paying higher prices for crude oil. Crude oil affects everything, including petrol and food.”

Striking a balance in the oil market is especially important now, as countries attempt to kick-start their economies after the devastating impact of Covid-19, Sehlake said, adding: “Crude oil is such an important commodity … So when everything stops it becomes a big problem.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

South African National Energy Association board member Dave Wright said if the stalemate continued and Opec+ was not able to add more barrels to the market, “at some point the price is going to get too high and people are going to start screaming”.

Prices would likely creep up for the next two to three months and the temptation to pump more oil into the market may cause even more cracks in the Opec+ alliance, he said.

“It could become a total free-for-all … The problem with it becoming a free-for-all is that you then get this kind of feast-to-famine experience when the price will drop dramatically,” said Wright, adding that the rift also brought the cartel’s credibility into question.

“I think that pressure will bring them to some settlement, so they can continue to manage the supply side and manage the price.”

The other major risk, according to Wright, is that prices could crash if the UAE decides to step away from the alliance and open the taps.

“If they can’t get to an agreement and the UAE decides to go ahead and use its increased capacity that it has invested in, then we swing very quickly from an undersupply position to an oversupply position. And the consequences will be that prices come tumbling down. I think that’s the last thing that the bulk of the Opec+ group wants,” Wright said.