Trouble: People are rescued from flooding in Lephalale. A climate change expert cautions that 3°C to 4°C of warming from 2041 to 2060 would be catastrophic for the area. Photo: Felix Dlangamandla/Gallo Images/Foto24

It was a sweltering 35°C in Lephalale, in the last week of September, but Elana Greyling said it felt more like a searing 42°C. “I always say that it’s 35°C in the shade with a cool room and the doors open,” said the chair of Concerned Citizens of Lephalale.

Greyling, who has lived in the coal mining town in Limpopo’s Waterberg district for 27 years, is used to the dry and harsh conditions of the arid bushveld region. But it’s getting hotter, she said.

“We’re definitely seeing the effects of climate change with these high temperatures. We’ve already had extreme rainfall with some floods in the area last year — it used to be once every 20 years or so but it’s happening more often,” she said. “Climate change is not the future anymore, it’s now.”

These climate-driven effects will worsen in Limpopo/Lephalale, according to a new report by global change expert Nicholas King. The report describes how climate warming in South Africa’s already drier and hotter interior that is “occurring faster than elsewhere” will “almost certainly deliver significant negative impacts on livelihoods”.

His expert report was one of two examining what South Africa will be like over the next 50 years if a business-as-usual approach to climate change continues. The reports were commissioned by the Centre for Environmental Rights for the African Climate Alliance, groundWork and Vukani Environmental Movement in Action as part of their #CancelCoal campaign.

‘Limpopo uninhabitable’

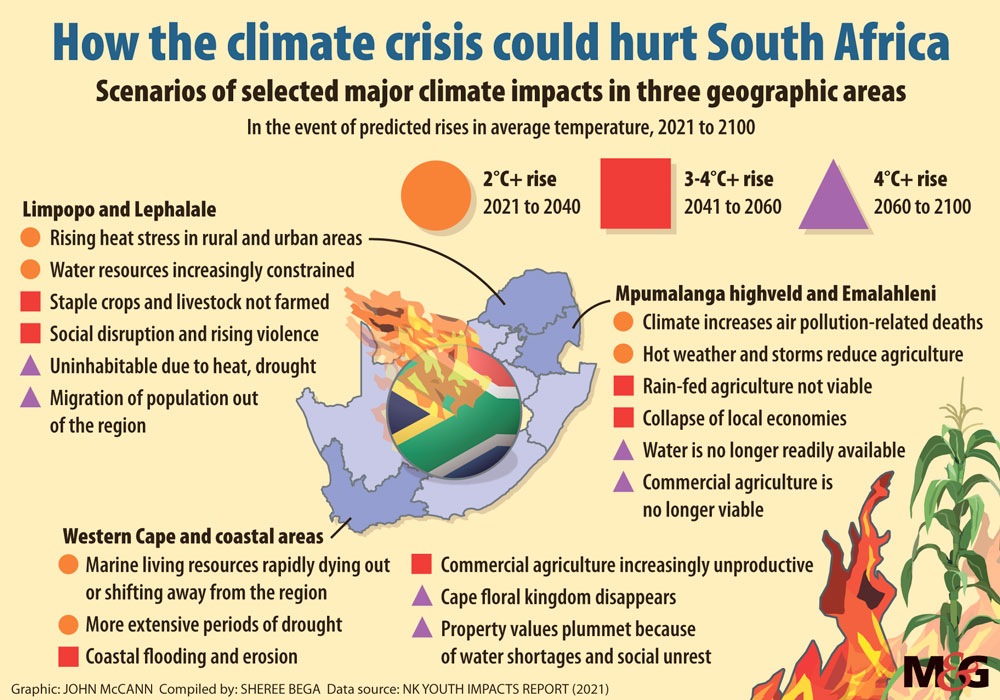

For Limpopo/Lephalale, 2°C of climate warming between 2021 and 2040 means that people will very likely no longer be able to depend on rain-fed agriculture and rangeland grazing for livestock, according to King’s report.

The rainfall that does arrive will increasingly “come in extreme events”, including hail storms and tornadoes, which will destroy crops, kill people and livestock, and damage homes and buildings. Food insecurity will probably quickly become a major cause of socioeconomic stress.

“Commercial farmers will probably struggle to obtain sufficient irrigation water, and conflict over water use and allocations will rise,” he wrote. “It’s very likely that service delivery protests in this region will shift focus to also include protesting against big water users such as mines, power stations and commercial farming as people struggle to obtain water for domestic use against a backdrop of rapidly rising temperatures and extended drought regimes.”

Hotter temperatures will make working outdoors more difficult, adding to physical harms and food insecurity. And as the surrounding bushveld dries out, this will exacerbate fire risks, which threaten life and property. Traditional coping mechanisms such as foraging for bushmeat will no longer be viable options.

King predicted that with 3°C to 4°C of warming from 2041 to 2060, most staple crops and livestock will “no longer be farmable” because of drought and heat stress, causing significant social disruption and rising violence. In the 2060 to 2100 period, which will see 4°C of warming, Limpopo/Lephalale will have turned into a “largely uninhabitable area”.

Greyling said the future “seems like an apocalyptic sci-fi movie but it’s our reality. And we have to fight. We live here because it’s the most beautiful place in the world. And we do pray and hope that people will wake up before we get to this terrible future that’s predicted for us.”

Cyclones for Mpumalanga

The same climate effects experienced in Limpopo will “undoubtedly” manifest in Mpumalanga, according to King. Air pollution from coal-mining and coal-burning on the Mpumalanga Highveld will almost certainly continue, at least in the short-term, “compounding the co-morbidities” that climate stress will bring such as heat stress, compromised water availability, water quality and sanitation.

He said tropical cyclones will probably extend increasingly further inland, bringing flooding to the region and east coastal belt with the destruction of infrastructure, socioeconomic disruption and loss of lives.

As these storms intensify, the effects are likely to outstrip those of Cyclone Idai in March 2019, which displaced more than 2.2-million people and destroyed the city of Beira.

The potential for a related disaster, such as the bursting of one or more major Highveld dams, including the Witbank Dam or Loskop Dam is “as likely as not”. Continued migration to the province’s industrial centres, driven by the harmful effects of climate change, will complicate socioeconomic issues.

From 2041 to 2060, these dire socioeconomic conditions will be exacerbated by the “rapidly advancing coal-death-spiral” from the necessary countrywide transition from coal to renewable energy, leading to unprecedented job losses through the “lack of just transition planning”, King wrote.

Western Cape bleak

From 2021 to 2040, water for basic needs will almost certainly become increasingly unavailable in the Western Cape, according to King. Although desalination may provide a short to medium-term solution, in the longer term, the vulnerability of coastal infrastructure to extreme storm events “will very likely negate this option”.

“Residents of massively expanding informal settlements such as Khayelitsha will spend much of their days waiting in queues at standpipes where these exist, or paying exorbitant prices for tanker water. Personal health will very likely be compromised by poor sanitation,” he wrote.

Service provision will become increasingly difficult, “unable to keep up with the rapidly expanding informal settlements as people migrate in from across the sub-continent, driven off the land by climate impacts and social disruption”.

Much of the provincial economy, dependent on agriculture and tourism, will probably be severely reduced, while increasingly, the biodiversity attractions of the Cape floral kingdom will be lost because of “the increasingly unsuitable climate envelope” and associated extreme weather events, including extreme fire outbreaks, reducing the region’s tourism potential, worsening unemployment and economic hardship.

“Although we do not have the answers as of yet, we do understand the severity of the situation,” said Jannie Strydom, the chief executive of Agri Western Cape.

“The matter of climate change requires all hands on deck, and the only possible way forward we can foresee, is that of a joint effort from government, the private and agriculture sector.”

From 2041 to 2060, climate change will have devastated the agricultural, tourism and hospitality sectors, given the collapse of wine-farming, coastal zone attractions and loss of the Cape floral kingdom, warns the report. “Coastal property prices are likely to have collapsed due to sea-level rise and storm-surge coastal erosion and damage to property and transport networks along the coastline.”

Sanele Zulu, the chief executive of the Green Youth Network, explains how the group inspires and trains young people to work in the agricultural sector. “But climate change is a threat to these jobs … We must take climate change seriously for what it is — a threat to society, to livelihoods and the future of young people.”

‘Significant harms’

King writes that South Africa will suffer enormous negative physical, socioeconomic and ecological harm under all climate scenarios, including extreme heat stress, extreme weather events, crop failures and food insecurity, water stress, disease outbreaks, various forms of economic collapse, social conflict and mass migration to informal settlements around urban areas.

“Impacts do not rise linearly with rising temperature, but with an ever-steepening curve, rapidly making large parts of the interior of the country, as well as vulnerable low-lying coastal areas, uninhabitable.

“All these impacts together will dramatically alter the lives and prospects for today and tomorrow’s youth, who will suffer significant harms, in a combination of detrimental physical health and wellbeing, mental trauma, social upheaval and reduced opportunities for self-advancement.”

He said that addressing rising disaster relief costs and rebuilding will become increasingly unaffordable for a country with a weak economy, massive unemployment, the world’s greatest inequality and the ensuing growing demands for social support.

Every additional greenhouse gas emission worsens the outlook, he writes. “Without every effort possible to mitigate emissions, most specifically through cessation of use of fossil fuels, the lives of today’s youth and future generations will be profoundly negatively impacted by climate change.

“Within a decade we will very likely be looking back on today’s extreme events as mild.”