Hooking us in: 'Untitled (Jordan 1s)'. Ramkilawan likes to immortalise memories in her work. ( Talia Ramkilawan)

“Being creative in lockdown is harder than I thought it would be,” reads an email from textile and tapestry artist Talia Ramkilawan. Since completing her postgraduate diploma in education last year, Ramkilawan is a full time artist and high-school fine arts teacher. She is currently preparing works for her first solo exhibition at Smith Studio.

Ramkilawan’s work aims to address and subvert the traumas inherited from generational and systemic erasure, displacement, assimilation and censorship. Through portraiture, it seeks to expand and affirm the presence of South Asian imagery by South Asian artists in South Africa’s contemporary art landscape.

“It’s based on my family dynamics and my experience with South Asian identity, culture and trauma … It’s about how I navigate living with so many intersections: Indian, yet not Indian enough; queer, brown, tired, yet with so much to give the world,” Ramkilawan says.

Untitled (nike), 2019. (Talia Ramkilawan)

Untitled (nike), 2019. (Talia Ramkilawan)Joining Ramkilawan in this state of perpetual uncertainty about where to belong are eight other Desi practitioners: Githan Coopoo, Youlendree Appasamy, Kate’Lyn Chetty, Alka Das, Tyra Naidoo, Tazme Pillay, Akshar Maganbeharie and Saaiq’a.

Together they have formed the Kutti Collective, an ensemble of South African Indian artists from Jo’burg, Cape Town and Durban who use arts, culture and academia to transcend the world’s expectations of an Indian experience beyond just the art world. They garner more visibility as a collective and, as Ramkilawan notes, “Surrounding myself with people who get me on so many levels has given me incredible assurance and the type of confidence I couldn’t achieve alone.”

The subjects depicted in Ramkilawan’s work are brown womxn. And to avoid perpetuating the trauma she aims to subvert, the work shows the subjects who Ramkilawan wants to celebrate in a space that erases traumatic triggers.

Before rug hooking, her technique involves her drawing and painting her subjects on to the hessian cloth that serves as her canvas. Although some of the portraits reference photographs from her childhood or online images that resonate with her, Ramkilawan’s earlier works were visual takes on speculative fiction — a lot of them were “womxn I would just conjure into existence”, she says.

Of late, she is more inclined towards depicting existing scenes and people because, “I like the idea of immortalising these memories in tapestries.”

At a simple glance, the works seem to address the fundamental matter of representation. However, below the surface of their textured profile and vivid colours, the seemingly laid-back depictions subtly disrupt a number of norms and expectations through naming and a close look at the subjects’ gestures or accessories.

In self-portrait Untitled (Jordan 1s), 2020, Ramkilawan wears a checkered dress with Jordan sneakers while holding an unwavering stare. Her body language, particularly how she tucks her dress in so she can comfortably sit with her legs far apart can easily go unnoticed, almost as if the term “sit like a lady” does not exist.

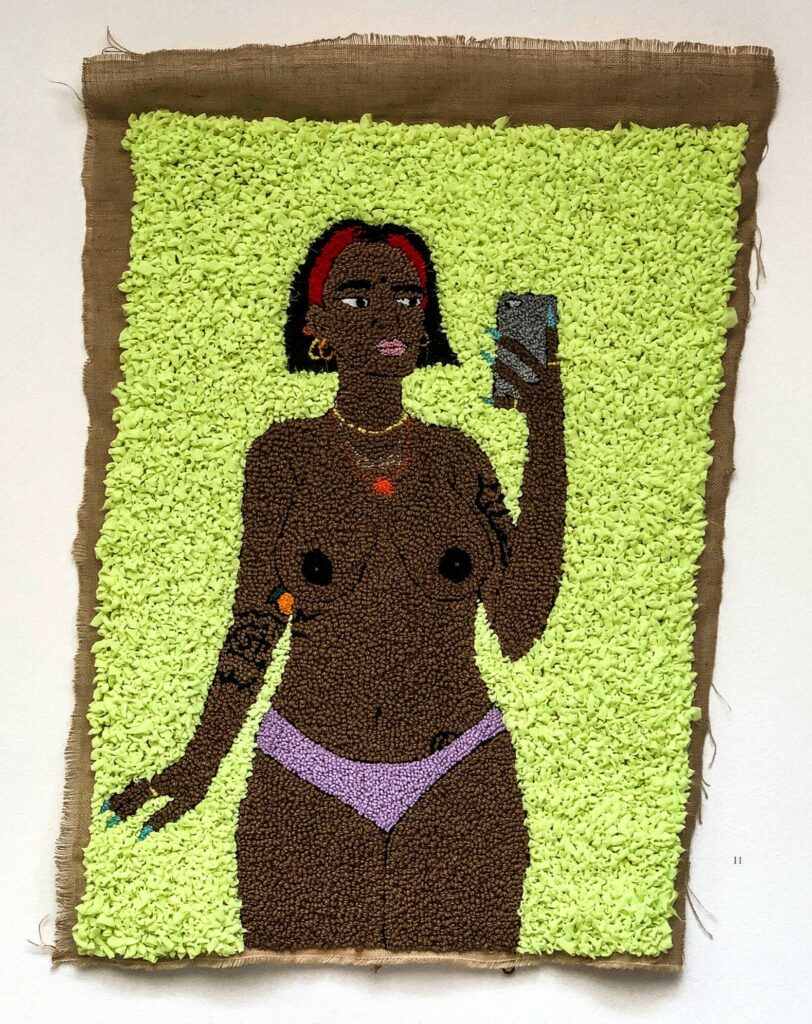

By naming her 2019 portrayal of a casual nude selfie You’re hot af for an Indian girl, Ramkilawan humorously encapsulates the absurd and violent ways that women’s bodies are often engaged with.

You’re hot af for an indian girl, 2019. (Talia Ramkilawan)

You’re hot af for an indian girl, 2019. (Talia Ramkilawan)

An example that uses both imagery and naming to disrupt the norm is How do you finger girls with those (2020), a piece that features a hand with long stiletto fingernails adorned with henna. Using both the title and visual cues, the piece highlights the many ways that heteronormative societies use questioning to invalidate queer intimacies, while it celebrates the fluidity of queer aesthetics.

Painting with yarn

In 2015, during her fourth year as a sculpture major at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, Ramkilawan grew despondent about the materials she had been accustomed to using for sculptural work. “I felt disconnected from the work I was making because metals and wood felt too harsh for the message I was trying to get across,” she says. To forge a sense of intimacy with her work, Ramkilawan thought it best to move from the rigidity of metals, stones and woods to the soft fluidity of tapestry.

Over the years, this textile art form has taken on diverse manifestations. There is El Anatsui’s assembly of recycled aluminium bottle-tops into cascading installations. Billie Zangewa made collages using silk patchwork. There are also works by the likes of Athi-Patra Ruga, Bulumko Mbete, Igshaan Adams, Kimathi Mafafo and many others to draw from.

When Ramkilawan began exploring the formats that tapestry has taken in contemporary art, she had planned to weave her works using a loom. While researching this weaving technique, she came across a carpet-making technique known as rug hooking.

When rug hooking, designs are actualised by threading yarn into an open-weave fabric like hessian or monk’s cloth using a punch needle. While threading the yarn through the material, it creates loops that come together to create a tufted, carpet-like texture on one side of the material and a smoother, embroidered texture on the other side.

Club Chai, 2020. (Talia Ramkilawan)

Club Chai, 2020. (Talia Ramkilawan)

Methods similar to this have recently gained local popularity after being used by the likes of Lazi Mathebula to make tufted sneaker rugs as well as by Keneilwe Mothoa for scatter cushions and framed portraits and still lifes. “I adapted the technique to tools and materials I had access to: a crochet hook, wool, and hessian stretched over a wooden frame,” Ramkilawan says.

Even though she was aware of sentiments that saw her shift as a safe bet because “working with wool and cloth is typically associated with women”, Ramkilawan knew it was the right direction to take her practice in because she found meditative solace in the repetitive threading motion used in rug hooking.

According to guided meditation platform, Headspace, “The idea here is that the subtle vibrations associated with the repeated mantra can encourage positive change — maybe a boost in self-confidence or increased compassion for others — and help you enter an even deeper state of meditation.”

Similar to mantra meditation, when the focus is on a mantra (which could be a syllable, word or phrase), Ramkilawan’s technique requires her to focus on a particular motion by repeating it. “Just by sitting in my apartment and appearing to play with wool all day, I’m doing internal work,” she says.

In addition to giving her work textured dimensionality, the rug-hooking technique’s allowance for everyday materials gives Ramkilawan’s portraiture a sense of domestic familiarity.

To see more of Talia Ramkilawan’s work, click here.