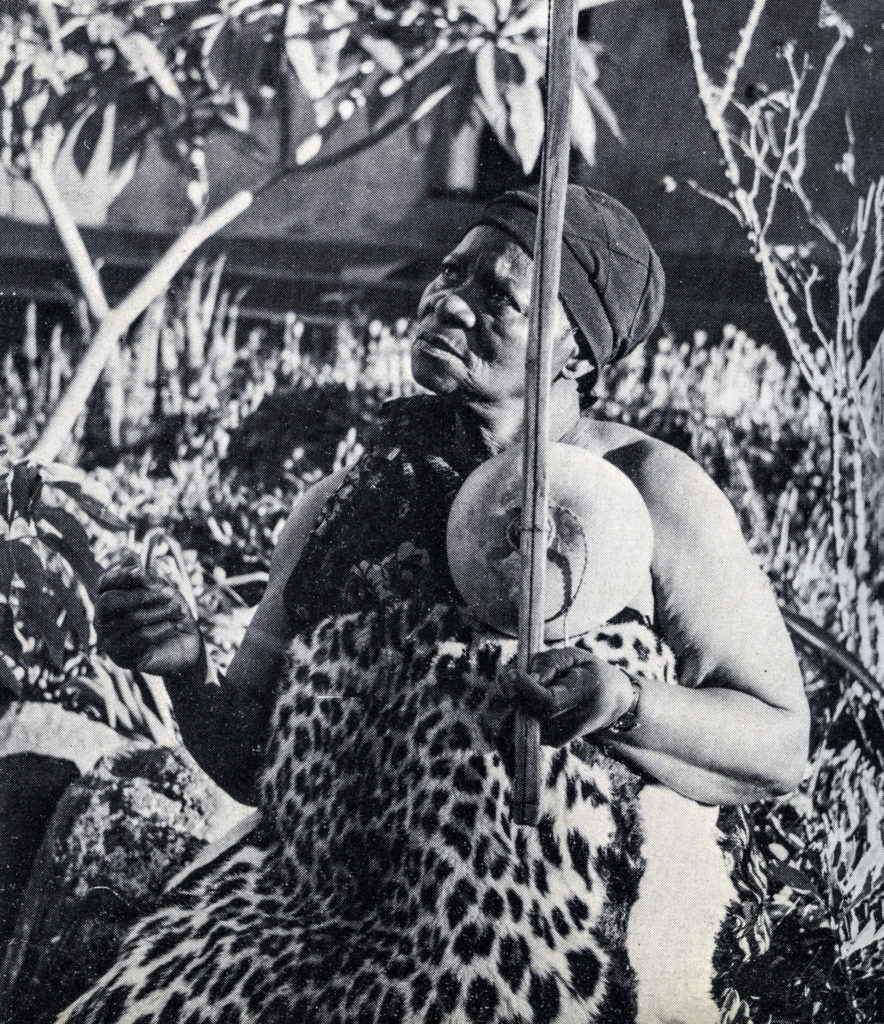

‘Tongues of their mothers’: The story of Princess

Magogo, playing ugubhu. (Supplied)

A little more than a decade ago, Makhosazana Xaba wrote the poem Tongues of their Mothers (found in the anthology of the same name). In it, she simultaneously yearned, lamented and envisioned.

“…I wish to write an epic poem about Princess Magogo Constance Zulu,

one that will be silent on her son, Gatsha Mangosuthu Buthelezi.

It will focus on her music and the poetry in it,

the romance and the voice that carried it through us.

It will describe the dexterity of her music-making fingers

and the rhythm of her body grounded on valleys,

mountains and musical rivers of the land of amaZulu.

I will find words to embrace the power of her love songs

that gave women dreams and fantasies to wake up and hold on to

and a language of love in the dialect of their own mothers.”

Although it is tempting to interpret this excerpt as an ode dedicated solely to Princess Magogo, it is important to resist this seemingly “obvious” impulse.

Xaba’s extract, which forms part of a larger text that centres on the narratives of various 18th, 19th and early 20th century South African (Black)women, demands a refiguring of the acclaimed and widely documented historical royal woman that many people know as “Princess Magogo kaDinuzulu”.

As demonstrated in Carolyn Hamilton et al’s book Refiguring the Archive, the idea of refiguring stems from the verb “figure”. According to the authors, this verb (which may also be used as a noun) means “to appear, be mentioned, represent, be a symbol of, imagine, pattern, calculate, understand, determine, [and] consider”.

Princess Magogo is often singled out as a sole proponent of often communally composed cultural songs (Supplied)

Princess Magogo is often singled out as a sole proponent of often communally composed cultural songs (Supplied)

Consequently, the addition of the prefix “re-” to the term “figure” suggests a re-turn (as seen in the Adinkra symbol of the rotating/kinetic Sankofa bird) to that which has been represented. In this context, the gesture of re-turning/returning is part and parcel of the desire not only to look back, but to do so with the intention of reimagining what one sees, hears and feels.

In her work, Xaba demands a daring move towards rethinking dominant representations of Princess Magogo. She does this in light of how the canon that is referred to as “Zulu historiography” or “official historiography” has written Princess Magogo into being.

In this milieu, it is a common practice to identify Princess Magogo primarily as the daughter of King Dinuzulu kaCetshwayo, the sister of King Solomon kaDinuzulu, the wife of King Mathole Buthelezi and the mother of Prince Mangosuthu Buthelezi. This apparent male-centredness in the telling of the narrative of Princess Magogo echoes Athambile Masola’s conception of the “absent presence of Black women” (as seen in her article “In search of my mother’s garden: iheritage yeblack female intellectuals”, Mail & Guardian, October 2017) in the South African historical and cultural landscape.

Masola’s assertion (which she specifically relates to Blackwomen writers such as Nontsizi Mgqwetho and Noni Jabavu) may be easily applied to the case of Princess Magogo and women in the Zulu monarchy at large. As Maxwell Shamase’s work around the figures he refers to as “Queen Nandi”, “Queen Monase” and “Princess Mkabayi Kajama” suggests, “official” historiography is a culprit in the marginalisation of the histories of women in the Zulu monarchy.

This claim may appear to be particularly ludicrous, given the extensive writings and documentation of Princess Magogo’s life story and multimodal works. However, as Michel Foucault’s notion of panopticism demonstrates, to be hypervisible (as an Othered or exoticised being) is itself an ensnarement that fixes one to the margins. This is to say that the hypervisibilised historic Princess Magogo, who is mostly confined to a homogenised and masculinised “Zulu” identity, exists without a community of women who played a critical role in her life as an artist and a royal woman.

Princess Magogo with her granddaughter, Sibuyiselwe, is best understood when situated within the community of the women who surrounded her. (Supplied)

Princess Magogo with her granddaughter, Sibuyiselwe, is best understood when situated within the community of the women who surrounded her. (Supplied)

The absent presence of this community of women is especially peculiar because of Princess Magogo’s own admission of their contribution to her multiple expertise, which the entire globe celebrates. In 1964, the ethnomusicologist David Rycroft — evidently deemed as one of the “foundational” scholars of Princess Magogo’s music — interviewed her at her homestead kwaPhindangene, Mahlabathini (located in what was then known as Zululand).

During their conversation, Princess Magogo noted that when she was a young girl (born in 1900), she slept in the homes of her many grandmothers (some of whom academic Innocentia Mhlambi names as OkaMkhayiphi and OkaMaganda) who played various instruments, including ugubhu, an instrument that she is world famous for playing. It is also worth highlighting that, in Rycroft’s paper “The Zulu Bow Songs of Princess Magogo”, Princess Magogo acknowledged the fact that she was under the tutelage of her mother, Queen Silomo Mdlalose, as well as her mother’s co-wives.

Although some historians, documentarians, ethnomusicologists, scholars and writers recognise the existence of Queen Silomo as Princess Magogo’s mother, they do so in passing. Very few people note that Queen Silomo composed poetry for her children. This was a common practice among isiZulu speakers, wherein mothers devised poems called izangelo for their newborns.

In her PhD thesis “Perceived Oppression of Women in Zulu Folklore: A Feminist Critique”, Norma Masuku frames izangelo in this manner: “These praises are recited by a mother when she is with a group of married women on a social occasion. In some cases, women have a special song that is sung after the praise poem. The poems are also recited by the mother to her child in the homestead, where the hidden complaints would carry particular weight. The mother is in [a] sense reciting the praise poem to and for her child, but she is also reciting it for the benefit of whoever else may be listening; if the persons referred to indirectly in the poem hear it, so much the better. The poem, however, is also recited long after infancy, on any occasion when a mother wishes to express, publicly or privately, the emotions of joy, pride or gratitude to her child”.

Considering Masuku’s claims, it is evident that when Princess Magogo was an infant (and well beyond that stage) — a scene that is hard to envisage in light of how Princess Magogo is often spoken of as a grown woman — her mother was already reciting poetry around her and to her. And because ugubhu was/is an instrument that was played mostly by women, it is not far-fetched to imagine countless instances where Queen Silomo sang about and for her daughter, who would herself become a singer, poet, instrumentalist and an all-round artist.

As suggested by Masuku, izangelo (and probably even the songs) that were performed by Queen Silomo were self-reflexive texts that reflected on her lived experiences. It was through these sonic works that Queen Silomo struggled against erasure.

The song Ngibambeni, Ngibambeni (from the album The Zulu Songs of Princess Constance Magogo KaDinuzulu) is a testament to the value of women in the lives of isiZulu-speaking societies. This sonic text that Princess Magogo said she learned as a young girl is predominantly understood to be a love song that is wholly dedicated to her husband (see Rycroft and others who cite him). However, the call “Ngibambeni, ngibambeni bomama!” communicates much more.

To conceive of this generational song as simply a dedication to the man Princess Magogo loved is a Hollywood-esque, couple-focused reading of this text. Although the songs found on her album are framed as “The Zulu Songs of Princess Constance Magogo KaDinuzulu”, it is critical to note that Princess Magogo herself admitted that she did not know the composers of some of the songs she sang, even though they had become primarily associated with her repertoire.

What is crucial about Ngibambeni, Ngibambeni is the invocation of older women while a young woman is in the throes of love. In the case of Princess Magogo, these women may be her grandmothers (whom scholars identify only as King Cetshwayo kaMpande’s widows), her mother and her mother’s co-wives (who are mostly unnamed).

Therefore, although this song is indeed about a young woman omuka nomoya out of being carried away by the overwhelming feeling of love for a young man she’s fallen for, it is the older women in her life that she calls upon for rootedness. It is these women … omama … ogogo … who she relies upon.

This is no surprise, considering the academic Babalwa Magoqwana’s conception of omakhulu or ogogo as “institution[s] of knowledge that transfer … not only ‘history’ through iintsomi [folktales]” but also “bod[ies] of indigenous knowledge that store … transfer … and disseminate … knowledge and values” (see Magoqwana’s chapter in the book, Whose History Counts: Decolonising Precolonial African Historiography).

In the context of the song sung by Princess Magogo, the idea of “umama” goes beyond the biological. In addition, the mothers who Princess Magogo calls out to are not just “Zulu” women: they are isiZulu-speaking women who come from multiple clans (with histories that precede the Shakan era), as seen in the genealogy of her mother, who comes from the Mdlaloses.

As aptly captured by Xaba, the story of Princess Magogo is one of many women. Her love songs (referred to by Princess Magogo as amahubo othando) are not just for the men in her life; they are also “songprints” (as seen in the work of Marie Rosalie Jorritsma), which speak in a dialect that touches on the multisensory experiences of Blackwomen.