Photographer Jurgen Schadeberg, 2016 (Alberto Domingo)

South Africa often doesn’t treat its legends well. Sure, we love and laud them, particularly when they win world cups and global acclaim. When they do us proud, wherever in the world they are, we pronounce them as our very own sons, daughters and siblings of the soil. And we hold them aloft. But we also tend to drop them. Often with a thud. Jürgen Schadeberg wasn’t dropped. But he was let down.

The legendary photographer, who passed away on Saturday at the age of 89, was not a natural-born homeboy. But his images immortalised some of the most epochal moments of South African modern history, in all its brutality, banality and exuberance. Yet even after being awarded lifetime achievement awards by New York’s International Center of Photography Museum, earning top spot at the Leica Hall of Fame in Germany, in 2014 and 2018, respectively, and being bestowed with an honorary doctorate at Spain’s University of Valencia, he couldn’t secure a South African gallery to showcase a smattering of seven decades of work.

He even struggled to get a local publishing house to back his memoirs. That was until Pan Macmillan stepped in and published The Way I See It: A Memoir — an unsanitised, behind-the-seams opus spanning his photographic and personal peregrinations from war-torn Berlin to the war rooms of South Africa’s print media and the brutal battlegrounds of apartheid South Africa.

Perhaps the publishers that rejected him preferred his pictorial style to his prose. Perhaps they didn’t like the way he wrote or how he saw it. Whereas his images monumentalised the most heroic and stoical moments of the men and women at the helm of the anti-apartheid struggle, his words prodded the untidy fissures camouflaged beneath polished public personae. And he didn’t shy away from meticulously detailed disclosures of the regular derailing and unravellings of perpetually hungover reporters and editors operating in dysfunctional newsrooms.

Today, Schadeberg is deservedly lionised as the photographer who helped to launch the careers of a generation of young black photographers who were unable to gain access to higher learning, who have become legends in and beyond their own lifetimes, and who went on to set the benchmark for today’s photographic practitioners. He partnered with brilliant, brave journalists determined to tell their own stories and who remain literary luminaries.

The gambling quartet, Sophiatown, 1953 (Jürgen Schadeberg)

The gambling quartet, Sophiatown, 1953 (Jürgen Schadeberg)

He helped to transform a hum-Drum magazine into Africa’s foremost publication on politics and culture. And, through his depiction of that wild, wanton and exuberant Drum era, he helped to perpetuate the image of the photojournalist as swashbuckling adventurer, lusting for life, love and a cold lager with equal ardour.

But Schadeberg was not a “shoot from the hip” kind of photographer, swaggering or staggering in search of the next adrenalin fix. He was a quiet, deeply sensitive, meditative practitioner, who unobtrusively moved through the spaces and moments he immortalised, extracting beauty from banality. He was very much a minimalist, who chose his shots carefully, fixating on details that the rest of us would dismiss.

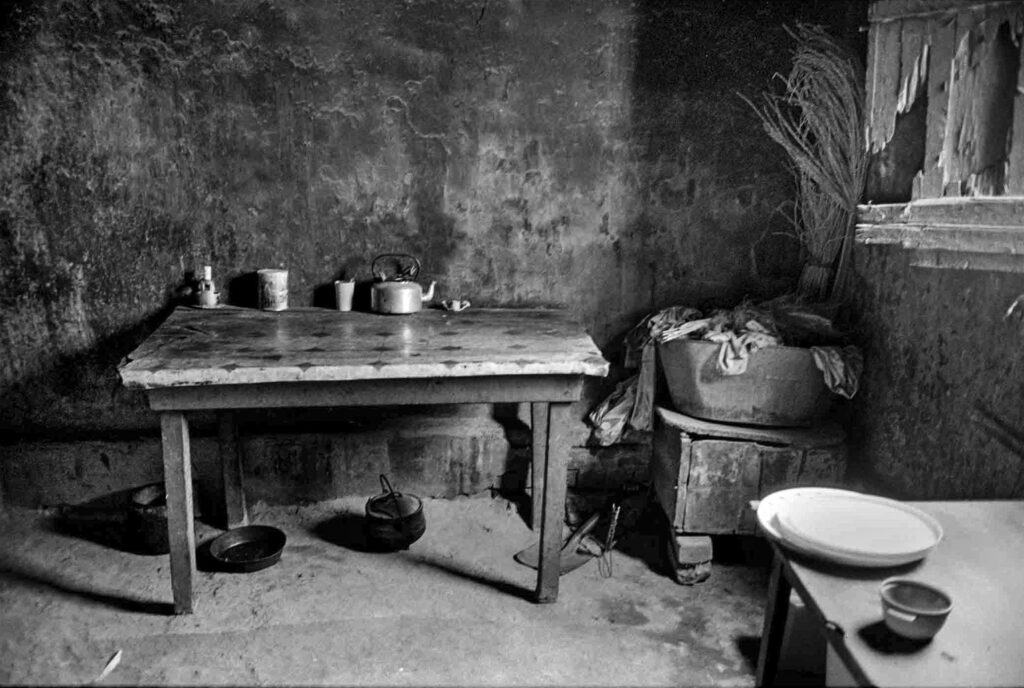

I learnt that about him in 2004 when we embarked together on a road trip from the Western Cape to the southern Cape, to document the appalling conditions of farm labourers in the rural areas. The expedition culminated in an exhibition and a book called Voices from the Land. The book didn’t gain much traction, despite its focus on the ongoing legacy of land dispossession in post-apartheid South Africa.

But it was during this trip that I witnessed first-hand Schadeberg’s delicate dance with light, framing, space and timing — his navigation of subtle differences from one second to another. He explained the magic about movement that flows; the imperatives of perfect timing, cadence and composition.

If this description reads like the review of a musical recital, it’s deliberate. Jürgen was a gifted guitarist with a passion for music that almost rivalled his love for photography. Also an accomplished painter, he approached light with an artist’s eye, combining the broad strokes of the impressionist with the pointillists’ meticulous attention to detail.

An interior from Schadeberg’s Voices from the Land series (2004)

An interior from Schadeberg’s Voices from the Land series (2004)

“You have to train your eyes to see,” he would say. “It’s like painting. You have to learn how a single zen brush stroke can depict a bamboo stick.”

I first met Schadeberg in 1988, when I was running the art and photo galleries at the Market Theatre. After leaving South Africa in 1964, and working in New York, London and Hamburg, he had returned 20 years later with his third wife Claudia, a Titian-haired beauty with an equal passion for film, literature, music and photography. His mission: to restore the thousands of negatives and prints from the Drum archive — now in a shambolic state — to their former glory and to use them to tell the history of South Africa in the 1950s.

He was also planning an exhibition and what better venue than the Market Theatre — a space that stood defiantly as a symbol of creativity and cultural unity during the death throes of apartheid. But he was justifiably horrified at my slapdash curatorial sensibilities. In softly modulated tones he eviscerated me for my sloppiness and I spat back.

After reducing me to the status of roadkill, he suddenly let rip with an unnervingly shrill giggle that evaporated the tension. That interaction and those “Jürgie-isms” cemented our friendship, heralding future collaborations and altercations, with Claudia sometimes interceding as referee.

He was a wonderful raconteur with an acerbic wit, a relentless drive and an intolerance for pretension. He was a purist and a perfectionist, uncompromisingly contemptuous of professional incompetence and political expediency.

An impromptu performance in Sophiatown, a suburb of Johannesburg, 1955. (Jürgen Schadeberg)

An impromptu performance in Sophiatown, a suburb of Johannesburg, 1955. (Jürgen Schadeberg)

And his vision did not allow for subtleties of grey. He was stubbornly dogmatic and dismissive of the postmodern confluence of art and photography with its whimsical pastiches and unashamed appropriation of imagery from the photographer’s lexicon.

“I am not an artist,” he would insist. “I am a photographer and one cannot authentically be that without a true understanding of the history and language of the medium.”

But his cantankerousness camouflaged a profound humanism, repulsed by racism both in his birthplace, Germany, and in his adopted homeland of South Africa.

“I would like him to be remembered most for his contribution to social justice,” ruminated Claudia, shortly after his death.

He was especially outraged by injustice, not only in terms of human-rights violations but intellectual and creative rights as well. He fought bitter battles against South Africa’s antiquated copyright laws that placed ownership and profit in the hands of the publisher, not the photographer. There were conflicts with Jim Bailey, the millionaire fighter-pilot and founder of Drum, whose personal idiosyncrasies and excesses were as legendary as the publication he spawned. The fracas lasted for years with claims and counter-claims that culminated in an uneasy truce.

There was also the widely publicised tussle with photographers Peter Magubane and Alf Kumalo over the authorship of an image photographed during the Rivonia Trial, when Magubane and Kumalo were cutting their photojournalist teeth at Drum. That spat seems to have been settled amicably. Then there was the controversy over his expedition with palaeoanthropologist, Professor Phillip Tobias to study the San of the Kgalagadi Desert, resulting in the 1982 photographic book The Kalahari Bushmen Dance. Decades later, in a 2019 exhibition at the Johannesburg Art Gallery, Tobias, a committed nonracialist —and Schadeberg, by association — were lambasted for objectifying the San. He weathered these storms, but they probably contributed to his growing sense of marginalisation.

His 2003 photographs on the socioeconomic disintegration of Kliptown — the site of the 1955 Freedom Charter — were ignored. His and Claudia’s documentary on Ernest Cole was rejected by the SABC.

He was angered by the governing party’s descent into kleptocracy. Although greatly admired by a younger generation of photographers, Schadeberg was becoming a relic, taxidermied to an era that he had long transcended. By 2007 it was time to leave.

His final years with Claudia in Valencia, Spain were peaceful and extraordinarily productive, with exhibitions and acclaim, worldwide. In a post-truth era of bullshit botoxed as fact, he remained authentically loyal to his truth.

And as he grew increasingly infirm, it was Claudia — his muse, his Mussolini — who devotedly drove him. He still had dreams: to buy a 4×4 and trek into the Valencia countryside to photograph the green, orange, lilac and vermilion landscape. He never did. By then, hands contorted by arthritis, he couldn’t even hold his precious Leica.